On June 12, Alberta (Canada) Premier Jason Kenney announced a multimillion-dollar lottery scheme to encourage more people to get COVID vaccines.[1]He said, “Many places around the world have launched similar lotteries like this because we need to just nudge those who haven’t gotten around to getting their vaccines yet.”

The appropriateness of that nudge is now the subject of spirited debate on various platforms. This article explores the uses of nudges to affect behaviour and how that fits in with BIG Media’s goals of objectivity, context, and reason.

Did you know that there is a wide body of evidence from behavioral psychology that human beings are subject to cognitive biases? [2]Did you know that there are also broadly understood indications that these biases are used to nudge (manipulate) your decisions?[3]This knowledge of psychology and choice architecture is not being promoted for use by individuals to make better choices for themselves but is taught as a tool for agencies to influence individuals to make choices that the agents select. Let us turn this upside down and position this knowledge for use by the individual.

We hope that this second in a series of articles aligns with the three aspirational words that BIG Media displays in its masthead: intelligence, logic, and respect. BIG Media also has the laudable goal of providing context to news. In a previous article (BREAKING NEWS… into rational pieces), we discussed critical thinking and the evaluation of news arguments. Let us continue our discussion of logic and the evaluation of information by exploring cognitive biases and nudges. Our ultimate goals are:

- To own the difficulties of our own raison d’etre – objective news reporting.

- To offer tools to help the reader resist being manipulated by news presenters. Including by Big Media.

Ask yourself while you read: can BIG Media deliver articles that are objective, factual, and in reasonable context?

Nobel Prize winner and author of Nudge, Richard Thaler[4], would likely answer that question with a BIG no. He and others have proven through experimental observations that, “[Humans] can be greatly influenced by small changes in context.” If BIG Media is trying to provide context, does that not suggest that despite its best intentions, this noble endeavour will fail to be perfectly objective at least some of the time? Another Nobel Prize winner, Daniel Kahneman,[5]has conducted numerous studies illustrating the many cognitive biases that human beings tend toward. The irrationality of human beings will surely affect both BIG Media’s writers and editors as well as its readers. Is BIG Media capable of the “logic” promised in its title?

Cognitive biases

A cognitive bias is a significant, measurable, or systematic deviation from normative expectations of rationality in judgment. [6]Put more simply, a person operating under such a bias is not seeing or treating the world objectively. Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow [7]summarizes the results of research on cognitive biases carried out by the author and other behavioral psychologists over several decades. Kahneman constructs a model of human cognition to explain these biases. In this model, our minds are said to have a fast, instinctive, or heuristic side, which he calls System 1, and a slow, logical, rational side, which he called System 2. System 1 is intuitive and prejudicial – and although it is essential in everyday operation – it also is the cause of most of the cognitive biases.

It is important to note that a cognitive bias is not deterministic; it is a statistical description of a particular tendency. Such tendencies are not guaranteed to be dominant and may be avoided through deliberate rational processes that call upon System 2. The list of cognitive biases is exceptionally long, and we will mention just a few of them in paraphrase of Kahneman.

- Anchoring is the tendency to be influenced by the first number or offer given, regardless of relevance or realism.

- Framing is an affect-of-choice context. The example given is a choice for surgery in which participants are asked if they would agree to surgery when told (1) that the survival rate is 90 percent or (2) if told the mortality rate is 10 percent. According to Kahneman, the first frame, which feels positive, is chosen more than the second.

- Availability is an effect in which humans assess the probability of an event based on how easy it is to come up with an example of a similar event. Availability cascades happen when the new media mention an event (e.g. earthquake, death due to a disease, vaccine hesitancy, global warming) so often that the feeling of immediacy and frequency of the event feeds on itself and becomes self-reinforcing.

- Representativeness is a stereotype based on similarity that affects the assessment of probability. Random coin tosses that come up heads several times in a row, for example, are often the subject of objection (the coincidence is denied) because three head tosses in a row is not representative of most people’s idea of random.[8]

- Loss Aversion is the tendency for subjects to take unreasonable chances or go to unreasonable lengths to avoid a potential loss.

- Overconfidence, or the mind thinks it knows, is the bias that Kahneman says affects people the most. Chance is underestimated, and control and understanding are overestimated.

- Status Quo is the preference for things to stay the same. It is a thoughtless, lazy choice that people tend to make, and it is a tendency that gets taken advantage of quite easily. It is one of the reasons that default choices are accepted unreasonably often and why nudges are effective. [9]

Nudges and libertarian paternalism

It did not take long before economists found a use for these cognitive biases. They quickly realized that these tendencies could be used in choice architecture to alter behaviour in a predictable manner, and they called this use a nudge. In effect, a nudge is the manipulation of choice through the use of cognitive bias or other irrational psychological tendencies.

Examples of nudges from Thaler and Sunstein:[10]

- The layout of items in a school cafeteria. If the goal of the school is to promote healthy foods, the healthiest foods (e.g. apples) will be displayed most prominently.

- Setting defaults to choices that are deemed good for the chooser.

- Savings plans with automatic contributions.

- Opt-out organ donation. The only way the state is not getting your organs when you die is if you specifically forbid their reuse.

- Up-selling and large portions. We tend to get up-sold and eat what is on our plate.

Thaler and Sunstein are careful to point out that a nudge is not deterministic; it does not force the chooser. They say that a nudge should not forbid options nor offer significant bribes. The nudge is supposed to influence choice in a way that the agent feels is in the chooser’s best interest. The supposed good intentions and preservation of freedom that Thaler insists upon led him to call nudges a kind of libertarian paternalism. The term, ‘libertarian paternalism’ even sounded sinister to Thaler. The idea is that it is possible, legitimate, and correct for institutions to affect choice while respecting freedom. Being nudged by the government is suggested as a better option than the government forcing top-down-style behaviour.

As proposed by Thaler, nudges do not sound sinister. However, the knowledge of nudges and their underlying psychology is now widely available and can be used by any actor, possibly in less benign ways than encouraging you to buy an apple instead of a bag of chips. Marketers and politicians can use nudges, too, and they may do so in less transparent ways than they should. Thaler’s concept seems to place a naïve trust on the agent of the nudge to act (a) in the best interest of anyone other than themselves, and (b) to legitimately leave other options open. Many supposed nudges are more like aggressive shoves.

Examples of such questionable nudges:

- Forced-choice travel insurance. The travel insurance is recommended, and a choice is required before buying the travel ticket. The problem here is that the insurance, objectively, is bad for most travelers.[11]

- Difficult-to-opt-out software defaults such as operating systems that push the software owner’s browser or other software, or electronic devices such as phones with defaults that are intrusive and difficult to disengage.

- Insurmountable paywalls. To sign up for a trial period of a service, customers are required to give credit card information. At the end of the trial, they would automatically be enrolled. The cancellation procedure is onerous and hidden.[12]

- News organizations framing COVID numbers to seem positive or negative to incite either fear of the disease or disgust at related public health restrictions. For example, “98% of people survive COVID”, or “2% of people die from COVID”.

- Alberta Premier Jason Kenney’s lottery encouraging COVID vaccination offers a significant bribe, or at least the near-infinitesimal possibility of one.

The concern is that outside agents are using nudges for their own gain rather than their customers’ best interest.[13] As beneficent as Thaler and Sunstein’s nudge concept appears, it still amounts to teaching outside agencies how to use cognitive biases to manipulate individuals. Why is there not a similar level of effort being put forth to help individuals overcome their biases and make rational decisions? Would it not have been better for Kenney to make greater efforts toward rational arguments for vaccination than offer a lottery-based bribe to Albertans using their own tax dollars? Three million dollars is a significant sum, and it must be asked if it should have been used to address the reasons for vaccine hesitancy rather than for a bribe. Why has so much effort and thought been invested in taking advantage of cognitive biases and so little on minimizing them and promoting reason?

My motivation for writing this article is to help its readers understand bias and resist such manipulation.

Can context be given without threatening objectivity?

It is possible to offer a choice without influencing that choice – without nudging? Can BIG Media provide context without nudging?

The answer to both questions is: no, or at least that it is almost impossible to do these things perfectly.

The problem is that we are affected by the environment in which we read news and make choices. The study of cognitive biases adds definition to the ways in which we are affected, but it does not create the bias. In fact, true neutrality is exceedingly difficult. In surveys, we can remove the default choice, which would reduce the influence on the system, but we still chose the order of the choices. Grocery stores and cafeterias still need to organize their foods. How can this be done without some influence – intended or not – since it is unlikely that a random layout of items (alphabetically, for instance) would be practical? If we removed all defaults from surveys and randomized cafeteria and grocery store layouts, would customers be happy? To some practical degree, defaults are unavoidable. Most customers don’t want to be forced to click more buttons or walk more aisles than they have to. The 98 percent survival or 2 percent death rate of COVID had to be reported in some fashion, and it can be challenging to report them with complete neutrality.

BIG Media’s writers may attempt to write their articles objectively, but the choice of articles that the organization undertakes may represent a lack of neutrality. This is a valid challenge to objectivity, but it is also a practical problem. BIG Media must choose its subjects somehow. And the more that BIG Media attempts to provide context, the greater the risk that it will instead provide bias.

In the next section, we will provide, dare I say, context to this problem.

Are we really so biased?

There is little doubt that the cognitive biases that Kahneman has identified, and Thaler advises governments and others to beneficently exploit, exist to some degree. Some might believe after reading myriad books, papers, and articles examining the subject, that human beings are incapable of overcoming bias and are hopelessly irrational. This grim conclusion is in error. These biases create a tendency toward error, not a guarantee of irrationality.

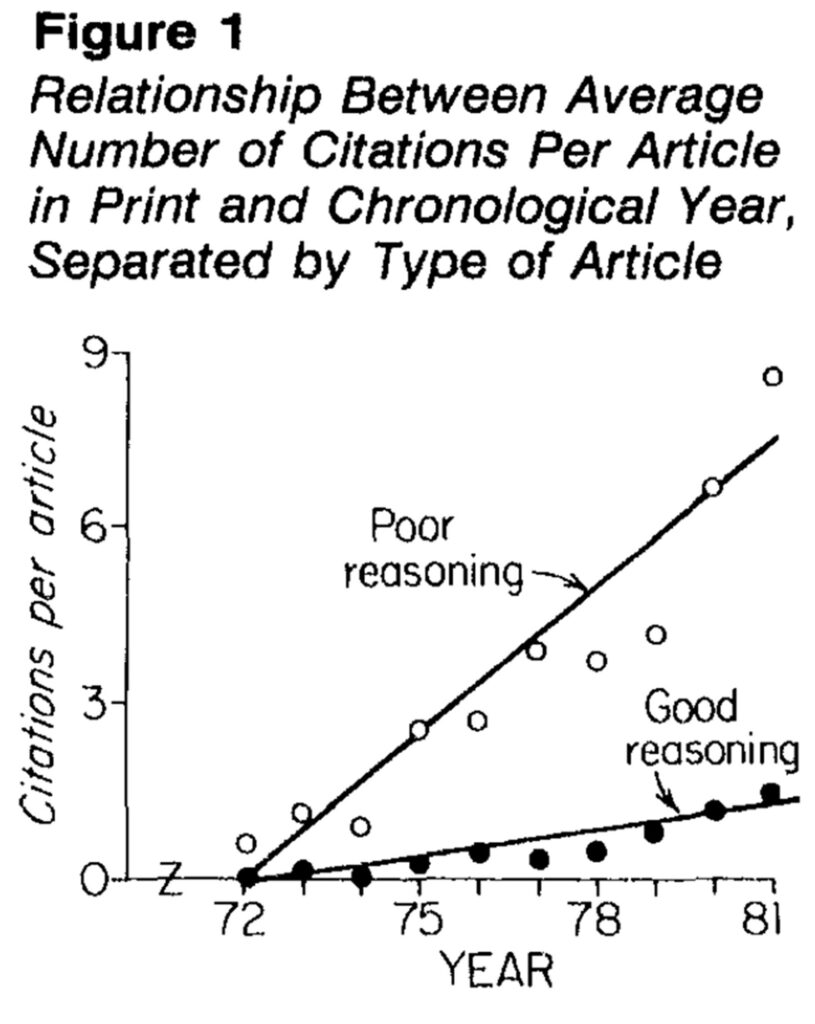

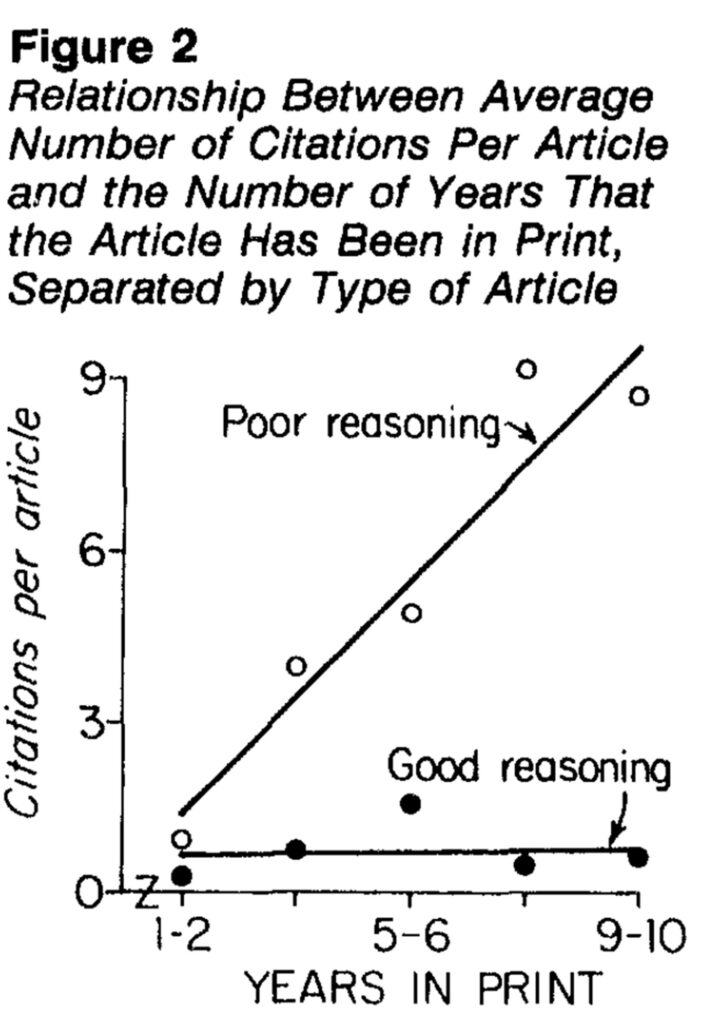

Social scientists and psychologists have mixed opinions on the level at which human beings reason. Many believe that we reason very well.[14] A study into citation bias has revealed that papers showing irrational decision making and failed reasoning are cited more often than the papers that show good reasoning. [15] Authors Christensen-Szalanski and Beach demonstrate this convincingly. The two figures below, which come from their article in American Psychologist, illustrate this. The authors claim that the papers showing ‘good reasoning” and “poor reasoning” were of the same average quality and appeared in journals of the same average popularity amongst researchers.

Figure 1 from Christensen-Szalanski and Beach in American Psychologist showing citation bias in favour of “poor reasoning” by year

Figure 2 from Christensen-Szalanski and Beach in American Psychologist showing citation bias in favour of “poor reasoning” by years in print

The authors offer this explanation for the bias: “When people behave the way they are ‘supposed to,’ it often does not seem particularly remarkable. But when people behave in what appears to be an irrational manner, it is not only remarkable, but we can give it a name.” This judgment was not appreciated by all researchers, one of whom wrote their own paper making the argument that the citation bias was not really so strong, and that it was wrong to write such a paper, it being a “Perhaps inappropriate question upon the judgment and decision making field.” [16] This last argument is specious; no scientist should hold their work or motivations above question.

An argumentative solution

An argument has been made by Mercier and Sperber that human beings reason best in an argumentative setting. [17] They have found numerous examples in the literature illustrating that the poor reasoning demonstrated in some of the tests are a result of the artificial nature and non-argumentative framing of the tests themselves. Here are a few of the deficiencies they found:

- Some tests, such as the Wason selection task, which involves cards with paired numbers and letters and an underlying rule,[18] were too abstract to engage participants.

- Tests involving logical syllogisms (“No C are B; all B are A; therefore, some A are not C.”) that would require participants to argue against their own conclusions may not reveal a deficient capacity for reason, but a lack of motivation.[19] When the answer is presented by someone else, participants showed much greater aptitude at attacking the problem and solving it correctly.

- Evidence (data) was unavailable to participants, forcing them toward casual theories or biases.

- The experimenter did not challenge participants to argue, such as with the Wason rule discovery task, which involves triplets of numbers and the assessment of their rule.[20] People tend to argue to the degree they feel is required. If there is no opposition, they argue lazily and tend to act with superficiality and bias. Real debate brought out the most reason.

- The tests of Kahneman and others generally lacked a back-and-forth element. Again, people reason best in argument.

Although our ability to reason is a function best activated by argumentation, it can lead to problems of its own. After all, winning arguments is not always the same as making good decisions. Some bias will arise from this fact. Sharon Begley, Newsweek’s science editor, reviewed Mercier and Sperber’s work and made a headline out of this, saying “Irrationality will be with us as long as humans like to argue.” [21] She is partially correct, but she missed the larger point, that the argumentative nature of human beings can also help us minimize bias and irrationality in many cases. Mercer and Sperber found that confirmation bias can be minimized by using group problem solving and leveraging the group’s argumentative nature. It turns out that confirmation bias is most strong in the production of arguments and least strong in the evaluation of them.

Processes

Knowing the name of the hundreds of catalogued cognitive biases is likely not an effective solution to overcoming them. Having a good set of analytic processes will go much further in preventing decision makers from falling prey to biases. No sample problem in Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow is difficult if the reader uses the correct process and a pencil, piece of paper, ruler, and Grade 8 algebra. Poor decisions can be made even by the vigilant if they fail to follow a rigorous process. For instance, draw a diagram, name variables, take an active part in solving problems. Adding mathematics and tools such as decision trees and decision analysis[22] to the argumentative context may help to further minimize the effects of cognitive bias.

What does this all mean for BIG Media and its readers?

Returning to our questions of “Are we capable of logic?” and “Can BIG Media deliver the news with both context and objectivity?” Yes, we are capable of logic and news can be delivered objectively, though we are unlikely to always succeed, and even our successes may be imperfect. That we will sometimes fail is a poor reason to give up. Besides this aspiration, we can use what we know about logic, and even about the quirks and biases of cognition to improve our objectivity. We can use both nudges and our tendency to debate together.

Choice architecture and the articles BIG Media publishes

There may be no greater unintended bias than the choice of articles we write. Despite its best intentions, BIG Media nudges its readers through these choices. It is almost impossible for BIG Media to avoid affecting its readers in this way. A completely unbiased default is difficult to put into practice. BIG Media must choose articles to write. But perhaps this can be minimized somewhat without disabling its core task of producing news. BIG Media should find ways to solicit from its readers at least some of the topics about which it chooses to write.

Nudging toward objectivity

As Thaler and Sunstein show, a voiced commitment to a goal helps nudge listeners toward that goal. The more we attempt to be rational and objective and enact processes to that end, the more we will succeed. The reader should never yield their agency as a rational human being and BIG Media should help by doing its best to provide news as objectively as possible. We can all help nudge each other to be better.

Context – nudging away from agreement and toward reason

We put context into our news. This context is meant to provide perspective on the information being evaluated. This context must be challenged. Because people argue best when motivated, and argue best against someone else’s opinion, BIG Media’s best hope of minimizing context bias is to incite counterargument. Or put another way, we must promote disagreement.

Let us put these ideas into the form of suggestions.

Suggestions for readers

- Consider all news with epistemic vigilance, [23] looking for counterarguments.

- Remember what you know about inductive arguments: look for truth (data), relevance, and adequacy. See this previous article (BREAKING NEWS… into rational pieces).

- Be aware of the likelihood that any news, purchase choices, surveys, online forms, behavioral suggestions, or negotiations are likely designed to nudge you into a certain “default” behaviour. Question the default.

- Talk about the news with friends who might disagree with you.

- Participate in debates over BIG Media’s articles. Voice your criticism and counterargument.

- Have a process for evaluating news.

- Do the math. When possible, draw a picture, identify variables and probabilities, and utilize mathematics.

- Draw a decision tree.

- Consider whether your taxpayer dollars should be used in nudges such as bribes as opposed to a greater investment in reasonable arguments.

There should also be a set of suggestions for BIG media involving the choice of articles and how to promote debate and criticism of its own work. In fact, a draft version of this article had several suggestions to this effect, all of which are currently being considered. Expect BIG media to publish a response in the near future.

[1] CBC / Radio-Canada, 2021, Alberta is offering $3M in lottery winnings to encourage people to get their COVID-19 vaccine

[2] Kahneman, D., 2011, Thinking, Fast and Slow: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

[3] Thaler, R., and C. Sunstein, 2008, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness: Yale University Press

[4] Thaler, R., and C. Sunstein, 2008, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness: Yale University Press

[5] Kahneman, D., 2011, Thinking, Fast and Slow: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

[6] Haselton, M.G., D. Nettle, and P.W. Andrews, 2005. ‘The evolution of cognitive bias’ in Buss D.M. (ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 724–746

[7] Kahneman, D., 2011, Thinking, Fast and Slow: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

[8] Thaler, R., and C. Sunstein, 2008, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness: Yale University Press

[9] Thaler, R., and C. Sunstein, 2008, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness: Yale University Press

[10] Thaler, R., and C. Sunstein, 2008, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness: Yale University Press

[11] Thaler, R., 2015, The Power of Nudges, for Good and Bad: The New York Times, 2015-11-01

[12] Thaler, R., 2015, The Power of Nudges, for Good and Bad: The New York Times, 2015-11-01

[13] Thaler, R., 2015, The Power of Nudges, for Good and Bad: The New York Times, 2015-11-01

[14] Doherty, M.E., 2003, ‘Optimists, Pessimists, and Realists’ in Schneider, S.L., J. Shanteau (ed.), Emerging Perspectives on Judgement and Decision Research: Cambridge University Press P. 643-676

[15] Christensen-Szalanski, J. J. & L.R. Beach, 1984, The citation bias: Fad and fashion in the judgment and decision literature. American Psychologist 39(1):75–78

[16] Robins, R.W., and K.H. Clark, 1993, Is There a Citation Bias in the Judgement and Decision Literature? ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR AND HUMAN DECISION PROCESSES 54, 225-244

[17] Mercier, H., & Sperber, D., 2011, Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory: Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34, 57-111. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000968

[18] Wason, P. C., 1966, ‘Reasoning’ in Foss, B.M. (ed.), New horizons in psychology: Penguin. P. 106–37

[19] Mercier, H., & Sperber, D., 2011, Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory: Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34, 57-111. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000968

[20] Wason, P. C. (1960) On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task: Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, Section A: Human Experimental Psychology 12(3):129–37

[21] Begley, S., 2010, Why Evolution May Favor Irrationality: Newsweek

[22] Newendorp, P. D., 1975, Decision Analysis for Petroleum Exploration, Pennwell Publishing Company

[23] Mercier, H., & Sperber, D., 2011, Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory: Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34, 57-111. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000968

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2021)

Good article, Lee. I will buy that book as soon as I finish the half-dozen I’m working on right now. But I have a feeling that no amount of intellectual reasoning will convince everyone to take the vaccine. I know a lot of very smart people who absolutely refuse to do it. They feel they are poisoning their bodies. Those of us who have had our double-dose may see this as selfish, but I do respect their right to refuse.