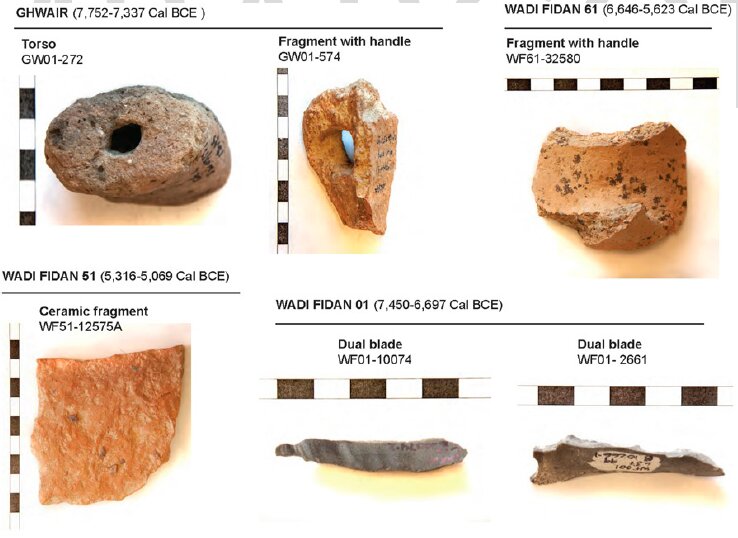

International research uncovered findings regarding the magnetic field that prevailed in the Middle East between approximately 10,000 and 8,000 years ago, Phys.org reports. Researchers examined pottery and burnt flints from archeological sites in Jordan, on which the magnetic field during that time period was recorded. Information about the magnetic field during prehistoric times can affect our understanding of the magnetic field today, which has been showing a weakening trend that has been cause for concern among climate and environmental researchers. The research was conducted under the leadership of Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef of the Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures at Tel Aviv University and Prof. Lisa Tauxe, head of the Paleomagnetic Laboratory at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, in collaboration with other researchers from the University of California at San Diego, Rome and Jordan. The article was published in the journal PNAS. Prof. Ben-Yosef explains, “Albert Einstein characterized the planet’s magnetic field as one of the five greatest mysteries of modern physics. As of now, we know a number of basic facts about it: The magnetic field is generated by processes that take place below a depth of approximately 3,000 km beneath the surface of the planet (for the sake of comparison, the deepest human drilling has reached a depth of only 20 km); it protects the planet from the continued bombardment by cosmic radiation and thus allows life as we know it to exist; it is volatile and its strength and direction are constantly shifting, and it is connected to various phenomena in the atmosphere and the planet’s ecological system, including – possibly – having a certain impact on climate. Nevertheless, the magnetic field’s essence and origins have remained largely unresolved. In our research, we sought to open a peephole into this great riddle.” The researchers explain that instruments for measuring the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field were first invented only approximately 200 years ago. In order to examine the history of the field during earlier periods, science is helped by archeological and geological materials that recorded the properties of the field when they were heated to high temperatures. The magnetic information remains “frozen” (forever or until another heating event) within tiny crystals of ferromagnetic minerals, from which it can be extracted using a series of experiments in the magnetics laboratory. Basalt from volcanic eruptions or ceramics fired in a kiln are frequent materials used for these types of experiments. An important finding of this study is the strength of the magnetic field during the time period that was examined. The archeological artifacts demonstrated that at a certain stage during the Neolithic period, the field became very weak (among the weakest values ever recorded for the last 10,000 years), but recovered and strengthened within a relatively short amount of time. Said Tauxe: “In our time … we have seen a continuous decrease in the field’s strength. This fact gives rise to a concern that we could completely lose the magnetic field that protects us against cosmic radiation and therefore, is essential to the existence of life on Earth. The findings of our study can be reassuring: This has already happened in the past. Approximately 7,600 years ago, the strength of the magnetic field was even lower than today, but within approximately 600 years, it gained strength and again rose to high levels.”

https://phys.org/news/2021-08-magnetic-field-years-today.html