The Women in Cleantech (WIC) Challenge is about to determine the $1-million winner of its three-year, six-female contestant challenge to produce sustainable, clean innovation solutions. The project ties together numerous important and topical issues: the environment and climate, sustainability and energy, inequality and diversity, nudging, social justice, and gender capitalism. Readers may wonder about the ramifications of applying a gender lens to the development of people and projects. What are the benefits and aims? Is applying a purpose-built gender bias in such a contest ethical and fair? Or is it a useful and good step in making Canada more competitive and the world a better place?

What is the Women in Cleantech Challenge?

The Women in Cleantech Challenge is a three-year program designed to help identify “top female innovators from across the country who are developing technologies to tackle the world’s most daunting energy and technological challenges.”[1] From hundreds of applicants, six women were selected for the contest, which has included financial support and technical and business advice to help them create their cleantech solutions. In September 2021, a winner of this $1-million challenge will be announced.

The stated goals are to help encourage these women to create valuable energy and environmental tech solutions resulting in a successful commercial venture.

Some might ask if applying a perspective that considers gender (a gender lens) to a technology venture is fair. Let us briefly examine the question.

STEM

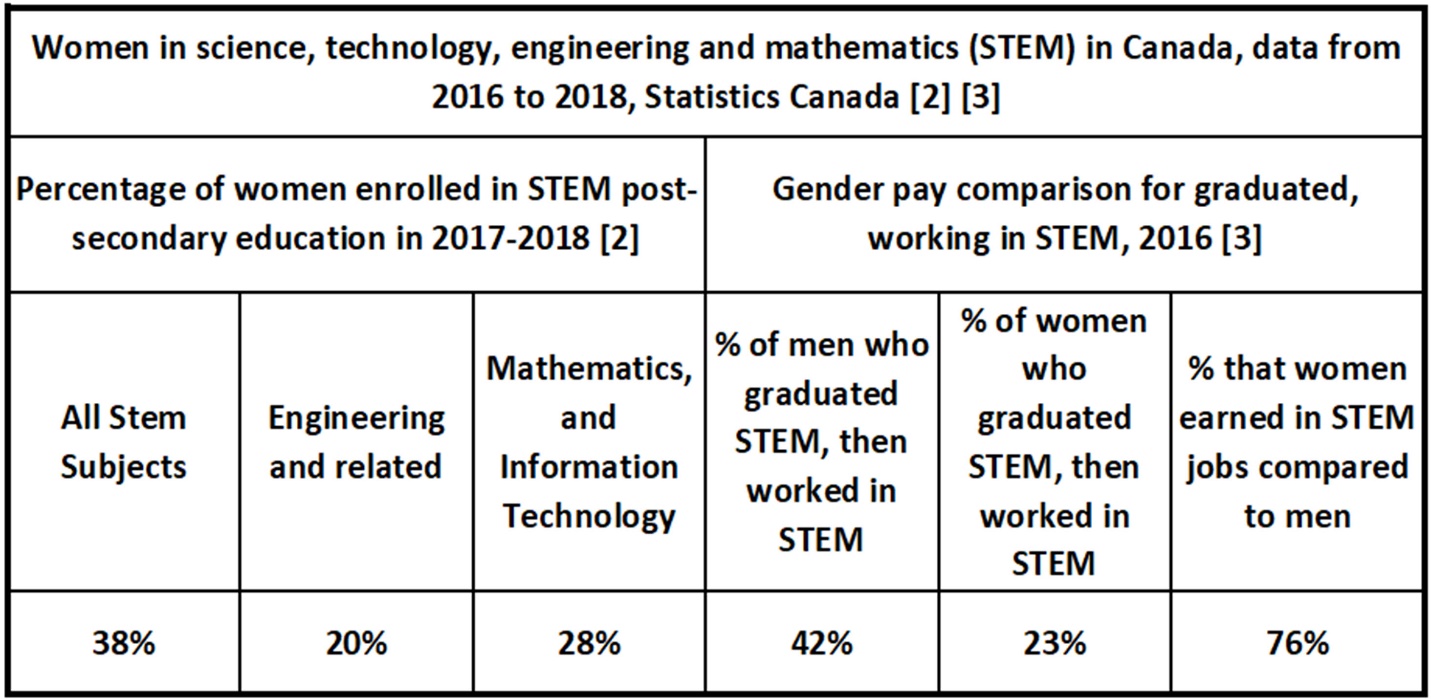

The WIC challenge would fall into a relatively high-paying and important disciplinary field called Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Studies collected by Statistics Canada and summarized in the chart below show that there is indeed a gender disparity in outcomes in Canada. Relatively less women enroll in STEM pursuits (38% compared to 62% for men), but less women who graduate in STEM actually work in a STEM career, and when they do, they tend to be paid about 76% as much as men.[2][3]

The Statistics Canada studies referenced here do not prove why these outcomes exist. Causality in a complex system such as who enrolls, graduates, and works in a field is very difficult to pinpoint, and numerous factors are involved. The pay gap, in which women are paid 76% as much as men in the same field, could be argued as indicative of both cause and effect.

Readers may reasonably ask if the 76% relative pay number is properly normalized for specific job and experience. The Economic Policy Institute discusses normalization for the gender pay gap in general and discusses STEM. While more specific estimates of the pay gap can be made, the pay gap numbers for STEM cannot be argued away by issues of normalization.[4]

Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) in Canada through a gender lens. Fewer women than men enroll in STEM subjects, a relatively lower number of women who graduate in STEM work in STEM, and they tend to be paid relatively less. Data from Statistics Canada.[2][3]

Women in leadership in Canada

The WIC challenge is not just about STEM; it is about leadership in the STEM field. A recent report called “Where’s The Dial Now?” co-authored by #movethedial, MaRS, and others attempts to describe the status of female leadership in STEM. The report shows an unapologetic bias toward the gender lens and promoting women in STEM. Its numbers for women in STEM careers are slightly different from the Statistics Canada reports referenced above (they speak to 2020, not 2016-2018, and there may be small differences in what they qualify as belonging to the STEM field), but they are not materially different or suspect. This report summarizes key outcome data in leadership, as follows:

- 5% of Canadian tech companies have solo female CEOs

- 13% of the executive team of the average tech company are women

- 8% of directors on boards of Canadian tech companies are women

- 12% of the partners in Canadian venture capital firms are women

Understanding the causal mechanisms for these outcomes in STEM and capital leadership is difficult, looking at the high disparity in STEM enrolment, employment, and pay.

The argument made in the “Where’s The Dial Now?” report is that this situation must change in order for Canada to be more competitive. The suggestion is that, whatever the cause, women are a valuable Canadian resource that does not appear to be appropriately utilized.

What is gender capitalism?

Gender capitalism is the application of a gender lens to investing.[6] The purpose of such an investment practice will not be homogeneous. A recent interview of Rotman professor Sarah Kaplan indicates that social justice for women – that is, ensuring greater fairness for females – is part of the goal. Kaplan reports similar numbers (6%) for venture capital funding of female-led business to the “Where’s The Dial Now?” report. Besides the reduction in bias and increase in justice, Kaplan suggests that gender capitalism may find “hidden opportunities” by better engaging women. She makes certain arguable suggestions toward the goals and methods of gender capitalism, such as considering gender quotas on boards, and assuming that there is a bias against women unless proven otherwise. That said, the central notion of enacting processes that help ensure a better and more productive role of women in the workplace is positive.

Concerns about a gender lens

Concerns regarding a gender lens include questions of causality and the worry that the focus will rest too heavily on outcome rather than fair process and merit. Since we cannot know what the “correct’ number of women versus men in STEM would be absent all bias, some readers may be concerned that the gender lens will force results in some new, biased way.

Programs such as the WIC challenge, which only allows female competitors, could be an example of a move toward unfairness. Such a large prize is beyond a simple nudge.[7] At the same time, with only 6% of venture capital going to female-run companies, contests such as WIC cannot be argued as suddenly creating a material bias.

It remains to be seen whether the gender lens and gender capitalism movement will lean toward the development of de-biasing processes that encourage all genders, or toward outcomes.

Arguments for a gender lens

The probability that certain gender biases exist in the workplace and within STEM is very high. While it is important to note that causality is not completely understood for the low relative numbers for women in STEM, the disparity in numbers is compelling. The wage gap indicates bias to a degree. It follows logically that developing even-handed processes to help encourage and utilize talented individuals of all genders in STEM is in the best interests of our society.

The possibility that better use of the talents of people in all genders could give Canada an advantage should not be ignored.

The WIC challenge will be an excellent opportunity to evaluate the utility of the gender lens and should be followed up on once the results are announced.

What is coming out of the Women in Cleantech Challenge?[1]

Readers can evaluate for themselves the value of WIC by its projects and their outcomes as they unfold. These projects appear timely and relevant. Brief descriptions for each project are given below, taken directly from the WIC website.[1]

Evelyn Allen (Ontario) has developed a manufacturing platform for producing large-area nanofilms made of graphene and other 2D “wonder” materials. Such films are increasingly used in cleantech applications, including water purification, energy storage, corrosion prevention, sensing, and smart packaging. The process developed is more energy efficient and aims to be dramatically less costly than existing approaches.

Julie Angus (British Columbia) has developed autonomous energy-harvesting boats that will transform oceanographic research, marine transportation, oil and gas, and defence. The boats will carry environmental sensors, cameras, and communication devices that will allow them to make oceanographic observations, act as communication gateways for sub-sea sensors, and more.

Nivatha Balendra (Quebec) has developed a sustainable way of remediating oil contamination, such as spills or tailings ponds, using biodegradable lipids produced by a specific strain of bacteria. The lipids are capable of breaking down hydrocarbons in a sustainable manner, unlike conventional approaches that rely on chemical detergents that are harmful to the environment.

Amanda Hall (Alberta) has developed an improved method of lithium-ion resource extraction from produced brine water. The approach has the potential to create an inexpensive and sustainable source of green lithium for batteries used in electric vehicles, portable devices, and mobile gadgets, all of which are fast-growing, multibillion-dollar markets.

Alexandra Tavasoli (Ontario) has developed a greenhouse gas (GHG)-to-fuel technology that converts waste CO2 or methane into syngas using solar energy and novel, nanostructured, light-activated materials known as photocatalysts. The approach could prove a powerful, energy-efficient way to turn CO2 captured from power plants or the atmosphere into clean chemicals and fuels.

Luna Yu (Ontario) has developed a solution that allows organic waste to be diverted from landfills and economically converted into a form of bioplastics called polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA). PHA bioplastics are fully biodegradable in marine and terrestrial environments. Products that can be manufactured from PHA bioplastics include packaging films, bags, containers, and utensils.

Interpretation

The gender lens in investment is likely here to stay and might practically be viewed in the same way that investors view any other important category of corporate governance and human resources. The effective and fair treatment of employees of every gender is an important goal not simply from the perspective of fairness, but from creating more effective businesses.

It is objectively inarguable that relatively few women enter STEM fields, and fewer yet receive venture capital support for their work. While we cannot easily assess the many causal mechanisms for this outcome, the gender wage gap may point to at least one cause. Programs such as the WIC challenge may aspire, through example, to ameliorate this situation in the short term.

Longer-term policies aimed at optimally and fairly encouraging the Canadian workforce toward valuable STEM careers are likely to be part of an ongoing conversation.

The winner of the WIC challenge will be announced in September. Perhaps readers will consider the outcome of the winning venture as they ponder the larger question of how to help create fair and encouraging environments for all Canadians to pursue their dreams.

[1] MaRS, Women in Cleantech Challenge.

[2] Statistics Canada, 2017, Is Field of Study a Factor in the Earnings of Young Bachelor’s Degree Holders? Census in Brief (November 29, 2017)

[3] Statistics Canada, 2016, Study: Gender Gaps: The Effects of Pay Transparency and Women in STEM Occupations, Statistics Canada press release, September 16, 2019.

[4] Gould, Elise, Jessica Schneider and Kathleen Geier, 2016, What is the gender pay gap and is it real?, Economic Policy Institute.

[5] #movethedial, 2017, Where’s The Dial Now? Benchmark Report 2017.

[6] Karen Christensen, 2015, The Rise of Gender Capitalism, Rotman Management Magazine, Wicked Problems III, Winter 2015.

[7] Hunt, Lee, June 18, 2021, Nudge and the uneasy pursuit of context and objectivity.

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2021)