India’s military skirmishes with neighbour Pakistan have dominated regional headlines of late, but today we take a look at the energy future of the world’s most populous country.

The Indian government’s National Institute for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog collaborated with the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay to update the India Energy Security Scenario (IESS) 2047 model. This amendment was accompanied by the release of the IESS 2047 Outlook, which explores future scenarios of plausible electricity demand, energy efficiency, and the share of alternative energy in the energy mix.

The aim of the updated Outlook is to encourage informed policy discussions on issues that affect the energy transition in India. Beyond India’s domestic energy transition aspirations, the Outlook helps sharpen understanding of how global energy markets might respond to an energy-thirsty India.

As India aspires to rank as the third-largest global economy by 2027, rising from its current fifth position, the document recognizes the role energy will play in this ascent. As the third-largest energy consumer globally, India expects expansion in its urban population, and industrial and infrastructure services. Further, it imports 40% of its energy requirement, so the expected change in demand must be factored into its energy security posture. Understanding the extent of India’s future reliance on coal to satisfy its burgeoning electricity demand is a critical consideration in the pursuit of global emissions decline.

In this piece, we will examine the methodology behind the outlooks, the specific scenarios deployed, the key metrics under the “business as usual” and “pessimistic” scenarios, and the strategic implications of the results.

Modelling India’s energy future: methodology and assumptions

The results in the IESS 2047 Outlook are derived from a “Bottom-up Energy System Accounting” model. This kind of model essentially projects national energy demand by aggregating demand from several end-use sectors (hence “bottom-up”) up to 2047. The resulting national demand is then matched by different energy supply sources under the assumptions of availability, penetration, and policy.

There are eight demand sectors and 17 supply sources modelled in the IESS 2047. The demand sectors:

-

- Industry

- Passenger transport

- Freight transport

- Commercial buildings

- Residential buildings

- Cooking

- Agriculture

- Telecommunications

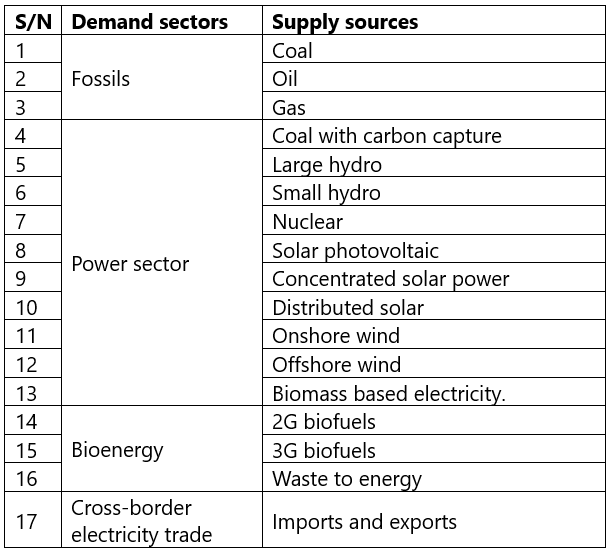

And supply sources and their categorizations are in Table 1.

Table 1 – Supply sources considered in the IESS 2047.

Sectoral energy demand is driven by the following factors:

-

- GDP

- Sectoral share of GDP

- Rate of urbanization and population growth

- Energy efficiency

- The model’s reference year is set at 2020.

Assumptions around the future evolution of these factors shape the trajectory of projected energy demand and corresponding emissions.

All about the assumptions

Although the modelling tool allows user-defined assumptions and customized scenarios, the default assumptions adopted in the IESS are summarized in the following tables. The results will be based on these default assumptions.

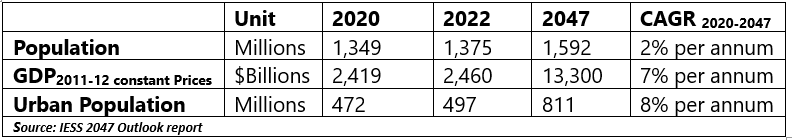

Population is expected to grow at a 2% per annum rate from 1.35 billion to 1.6 billion in 2047, while GDP grows from $2.42 trillion to $13.3 trillion in 2047 expressed in 2011-12 constant terms.

Table 2 – Population and GDP assumptions in IESS 2047.

Urban population, however, is expected to grow at a rate four times that of the general population. The 7% per-annum growth rate noted for GDP is consistent with the compound average growth rate (CAGR) from 2000 to 2020.

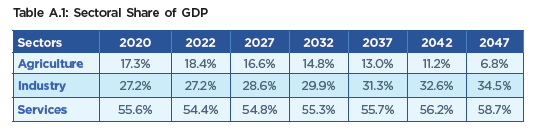

The sectoral contributions expected to the Indian GDP to 2047 is shown in the following snippet from the report. The services sector is expected to continue the dominance of its GDP contribution – rising from 56% (2020) to 59% (2047).

Table 3 – Sectoral share of GDP (Source: IESS 2047 report).

The agricultural sector’s contribution to the Indian GDP is expected to shrink from 18.4% (2022) to 6.8% (2047), while the industry share rises from 27% (2022) to 34.5% (2047).

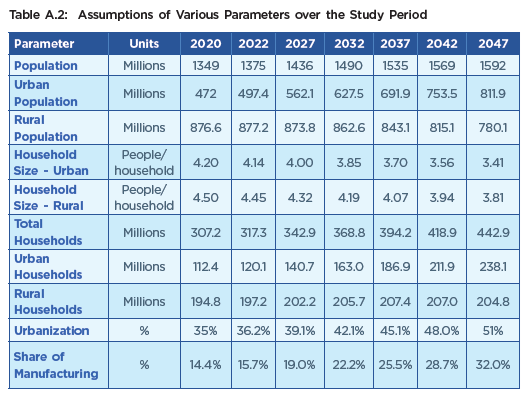

Table 4 compiles different parameters that convey the outlook around demographic changes. The population projections are based on data from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

Table 4 – Detailed demographic changes used in Outlook (Source: IESS 2047 report).

Household size in both urban and rural areas is expected to decline from their level in 2020. Urban areas are projected to see a drop from 4.2 persons/house to a 2047 level of 3.41 persons/house, and rural areas from 4.5 person/house to 3.81 persons/house. By 2047, 51% of the population is expected to reside in urban areas, up from 35% in 2020.

The emphasis on assumptions on population (and related demographics such as urban-rural split, household size) and demand sector contribution to GDP show a model with these two factors as the main drivers of energy demand. Energy prices, which obviously play a role in demand, have not been captured in the model. The report highlights this as a limitation of their approach:

“…These uncertainties (referring to fossil fuel prices) as well as oscillatory nature of prices have not been covered in the trajectories.”

These demographics and GDP structure will have implications for the quantity and type of energy consumed, and energy security implications.

To capture uncertainty: scenario modelling

Scenarios are used here to capture uncertainty. Different versions of the future can be created based on assumptions around the factors that drive sectoral energy demand. These assumptions are then embodied in the four scenarios or levels which capture the trajectory of end use demand and supply.

As Brad Hayes pointed out in an earlier article for BIG Media, the use of scenarios in energy modelling can be a double-edged sword.

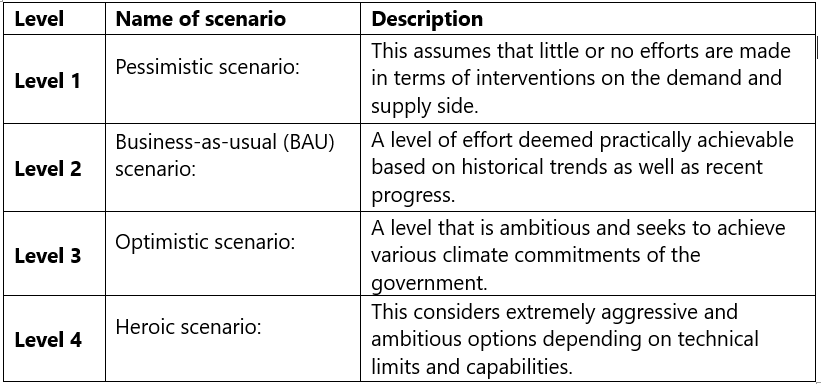

Table 5 is a description of the scenarios that adopts much the language used in the Outlook.

Table 5 – Description of Scenarios in IESS 2047.

In this article, we focus on the BAU scenario in comparison to the pessimistic scenario to present a cautious view of India’s energy future based on historical trends.

Model limitations

Every model comes with shortcomings due to tradeoffs that must be made in its design and construction – and the IESS 2047 is no different. The developers of the IESS 2047 acknowledge key limitations of their model, summarized as follows:

-

- Inability to ascertain the costs associated with any of the projected scenarios as critical renewable technologies are not costed.

- By ignoring energy prices and focusing only on GDP and population as demand drivers, we lack the ability to model the impact of prices on energy demand and supply.

- The model is not designed to produce an optimal energy demand/supply profile.

Despite these shortcomings, the model yields a practical, theoretical glimpse at India’s energy future.

Scenario analysis: business as usual vs. pessimistic pathways

In this section, the metrics I explore will be:

-

- Final energy demand mix

- Energy supply mix

- Import dependence

Let’s look now at how the metrics compare under the “business as usual” scenario (Level 2) and “pessimistic” scenario (Level 1).

Final energy demand mix

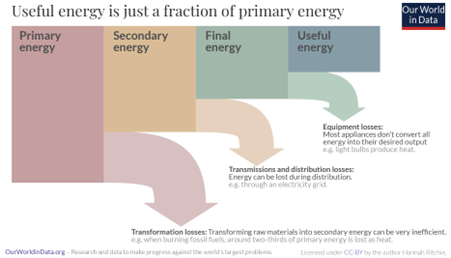

Total final energy demand captures the energy consumed by end-users such as individuals and businesses. It includes non-energy uses of energy products, such as hydrocarbon resources (fossil fuels) used to make chemicals.

This differs from primary energy, which is the energy available as resources before it has been transformed for end-use. For a pictorial view of how primary energy relates to final energy end-use, this graphic from Our World in Data is helpful …

Figure 1 – Illustration of primary energy supply and end-use energy demand sector (Source: Our World in Data).

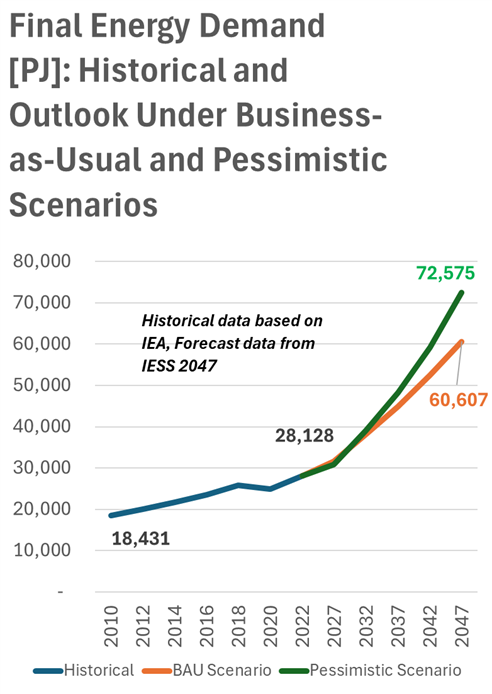

Figure 2 tracks India’s final energy consumption under each scenario. India’s final energy consumption in petajoules rose from 18,431 PJ in 2010 to 28,128 PJ in 2022, which is a CAGR of 4% per annum. Expressed in barrels of oil equivalent per day, that is an increase from 8.24 MMBOE/d to 12.59 MMBOE/d.

Figure 2 – India’s historic and projected final energy demand.

Under the BAU scenario, final energy demand is projected to double to 60,601 PJ (27.12 MMBOE/d) in 2047. Under the pessimistic scenario, it rises to 70,575 PJ (31.58 MMBOE/d). The pessimistic scenario is one in which the government does not exert effort to curtail energy demand. It is important to recognize that reducing energy demand is one of the Indian government’s strategies to attain energy security through reduced energy import dependency.

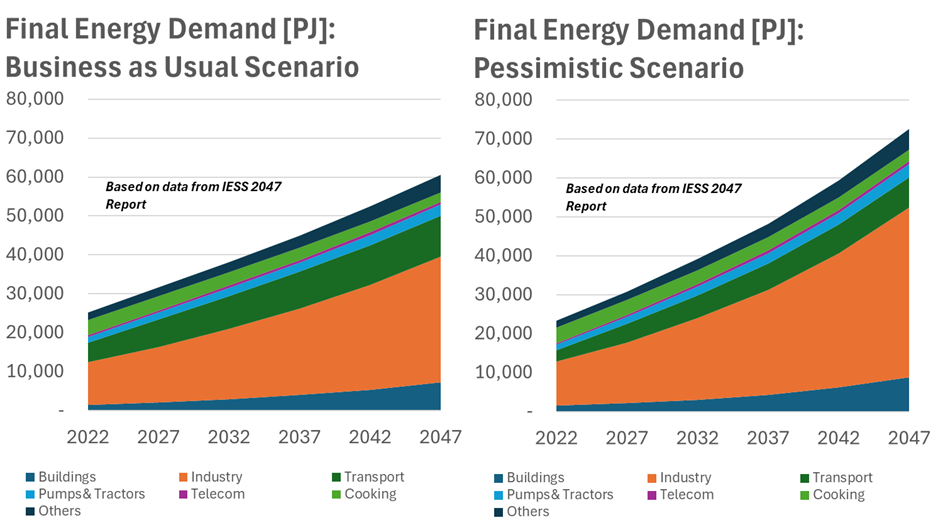

We turn attention now to the end-use sectors that make up the projected final demand. Under both scenarios, industry takes up the largest chunk of energy demand by 2047 – 54% of the final energy under the BAU, and 60% under pessimistic scenario.

Figure 3 – Final energy demand is driven by industry.

Industry demand grows at 4.5% per annum from 9,981 PJ (4.45 MMBOE/d, 2020) to 32,420 PJ (14.5 MMBOE/d, 2047) under the BAU. However, industry demand grows at ~6% to reach 43,680 PJ (19.54 MMBOE/d, 2047) under the pessimistic view.

Buildings take up about 12% of the energy consumed by 2047 under both scenarios driven by the envisaged high rate of urbanization, by then projected at 51%. This sector is noted to have the fastest energy demand growth rate at 6% per annum under BAU and 7% per annum under pessimistic.

Overall, final energy demand grows at an annual rate of 3.4% (relative to 2020) under the BAU, compared to 4.1% under the pessimistic scenario.

Energy supply mix: hydrocarbon resources and renewables in focus

So, into what energy sources will India tap to grow its energy consumption, achieve 7% GDP growth per annum, provide employment and upward social mobility to its population, half of whom will be urban dwellers?

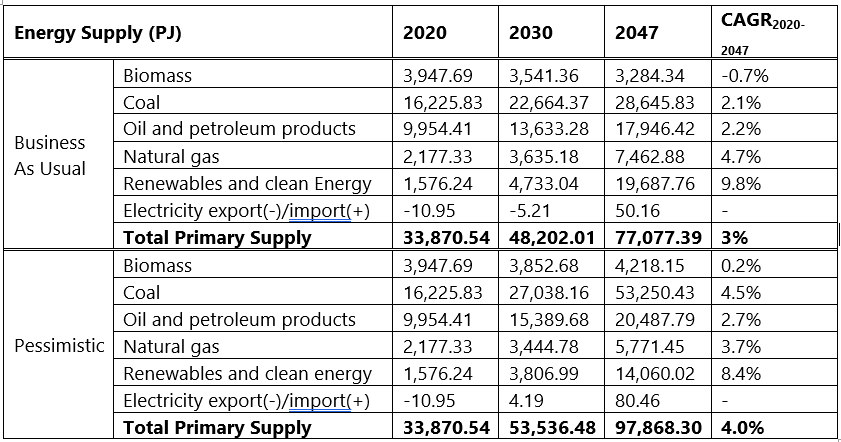

To answer this question, we refer to Table 6.

Under the BAU, coal, oil/petroleum products, and natural gas together supply 70% of the ~77,000 PJ of energy India needs by 2047. This is down from 84% of ~34,000 PJ energy supplied in 2020. Further, natural gas supply grows the fastest of the three fossil fuels at 4.7% per annum from 2020.

Renewable energy is expected to experience aggressive growth of 10% per annum up to 20,000 PJ, accounting for 26% of supply in 2047. Keep in mind that under the BAU scenario, the decarbonization policies of the government are assumed to be on track. Renewable purchase obligations (RPOs), tax credits, and favorable financing are expected to help achieve a 725-GW utility-scale solar PV plant by 2047.

Table 6 – India’s Energy Supply to 2047 (Source: IESS 2047 report).

India becomes an importer of electricity by 2047 of 50 PJ under the BAU, which increases to 80.5 PJ under the pessimistic scenario. Currently, India trades electricity with Bhutan, Nepal, and Bangladesh, which, in 2023 amounted to 21.53 TWh valued at $1.5 billion.

Under the pessimistic scenario, hydrocarbon resources supply 81% of the 98,000 PJ energy needs of India. In this scenario, coal is seen as the fastest-growing hydrocarbon fuel at 4.5% per annum from 2020. Renewables and clean energy account for 14% of the energy supply and would grow at 8% per annum from 2020.

This outlook emphasizes that hydrocarbons will play a key role in India’s economic growth aspirations if the country is to maintain its current decarbonization policies to 2047.

Import dependence – geopolitical risks and self-reliance

Concern about energy security dominates India’s energy policy objectives– and for good reason. In a world where energy has been weaponized for geopolitical gain, a country such as India – which imports 85% of its crude oil and 49% of its gas requirement – sees itself as particularly vulnerable.

The 2022 Independence Day speech by Prime Minister Modi called on India to be energy self-reliant by 2047 – when the country celebrates 100 years of independence. In hoping to inspire his compatriots to act, Modi said:

“We have to become self-reliant in the energy sector. How long will we be dependent on others in the field of energy? We should be self-reliant in the field of solar energy, wind energy, various renewable energy sources and must lead in terms of Mission Hydrogen, biofuel and electric vehicles.”

Consequently, the country’s energy policy choices weave the objectives of economic development, energy security, and net zero by 2070. Against that backdrop, we examine to what extent energy security is achieved along the chosen pathways.

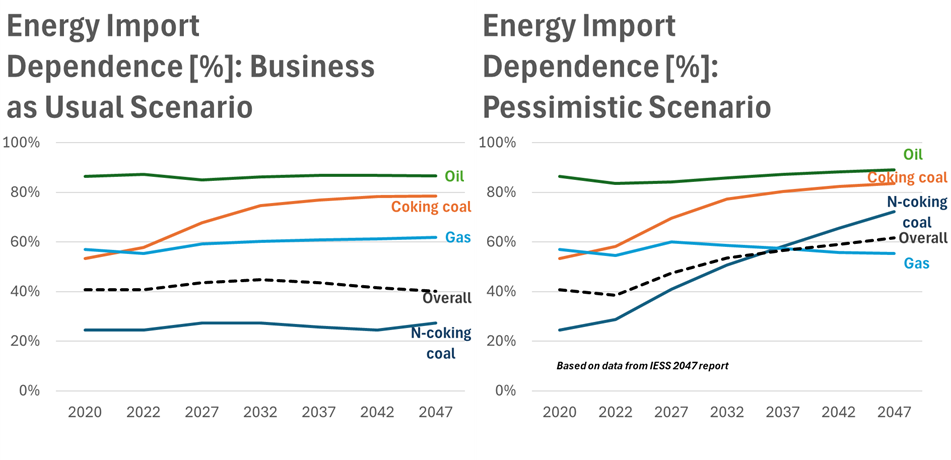

Energy import dependency, as one of the major determinants of energy independence, is the metric by which we look at energy security. Import dependency is simply the percentage of energy consumed that is imported.

If the government continues along its current path (BAU), 87% of crude oil consumed by 2047 would be imported. This would have been at the same level since 2027. Imports of coking coal would rise from 68% (2027) to 79% in 2047. Coking coal is used in steel-making, and India is deficient in this type of coal, despite its huge coal reserves. Even with domestic coal reserves, 27% of India’s non-coking coal needs are forecast to be imported by 2047. Overall, India, under BAU, would still import 40% of its energy requirements by 2047.

Figure 4 – Energy import dependence; India’s projected reliance on oil imports to 2047.

However, in a scenario in which there is slack implementation of decarbonization policies, India would find itself importing 62% of its energy needs by 2047. This higher import dependency would be driven by oil at 89%, coking coal at 84%, and non-coking coal at 72%.

India’s strategy for reducing import dependency is two-pronged:

-

- Reduce the demand for energy products

- Increase the domestic production capacity

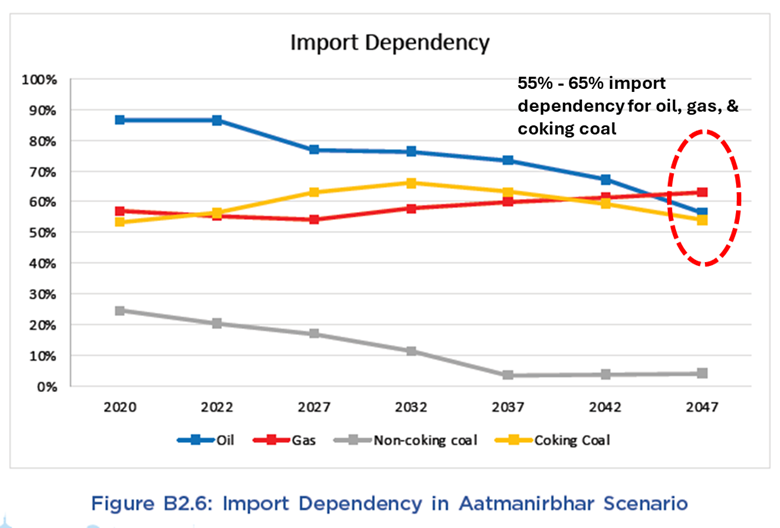

This strategy is modelled as the “Aatmanirbhar” scenario or “Self-Reliant” scenario. In this scenario, energy supply grows by 3% per annum to 73,780 PJ (33 MMBOE/d) in 2047 – only 4% lower than the energy supplied under the BAU. However, unlike the BAU scenario, hydrocarbon resources supply 50% of this energy, compared to 70% in the BAU.

Import dependence would be >50% for oil, gas, and coking coal, and only non-coking coal would have an import dependence less than 10%.

Figure 5 – India’s import dependency in Aatmanirbhar (“self-reliant”) scenario (Source: IESS 2047 Outlook).

In the self-reliant scenario, India’s energy supply is very close to that of the BAU scenario, but with lower share of oil, gas, and coal. Further, import dependency for hydrocarbons is lower under the self-reliant scenario than in BAU.

Strategic takeaways – balancing growth with security

India is on track to consume even more energy if it is to fulfill its goal of being considered a developed economy by 2047 – 100 years after its independence. Based on the examination of India’s IESS 2047, the final energy consumed by 2047 is projected to be between 2.5-3 times the 24,500 PJ (11 MMBOE/d) registered in 2020, of which 70-81% will be from fossil fuels.

Given that the country imports 89% of its oil, 45% of its gas, and 50%+ of its coking coal requirement, the energy security imperative of India depends largely on energy-exporting countries.

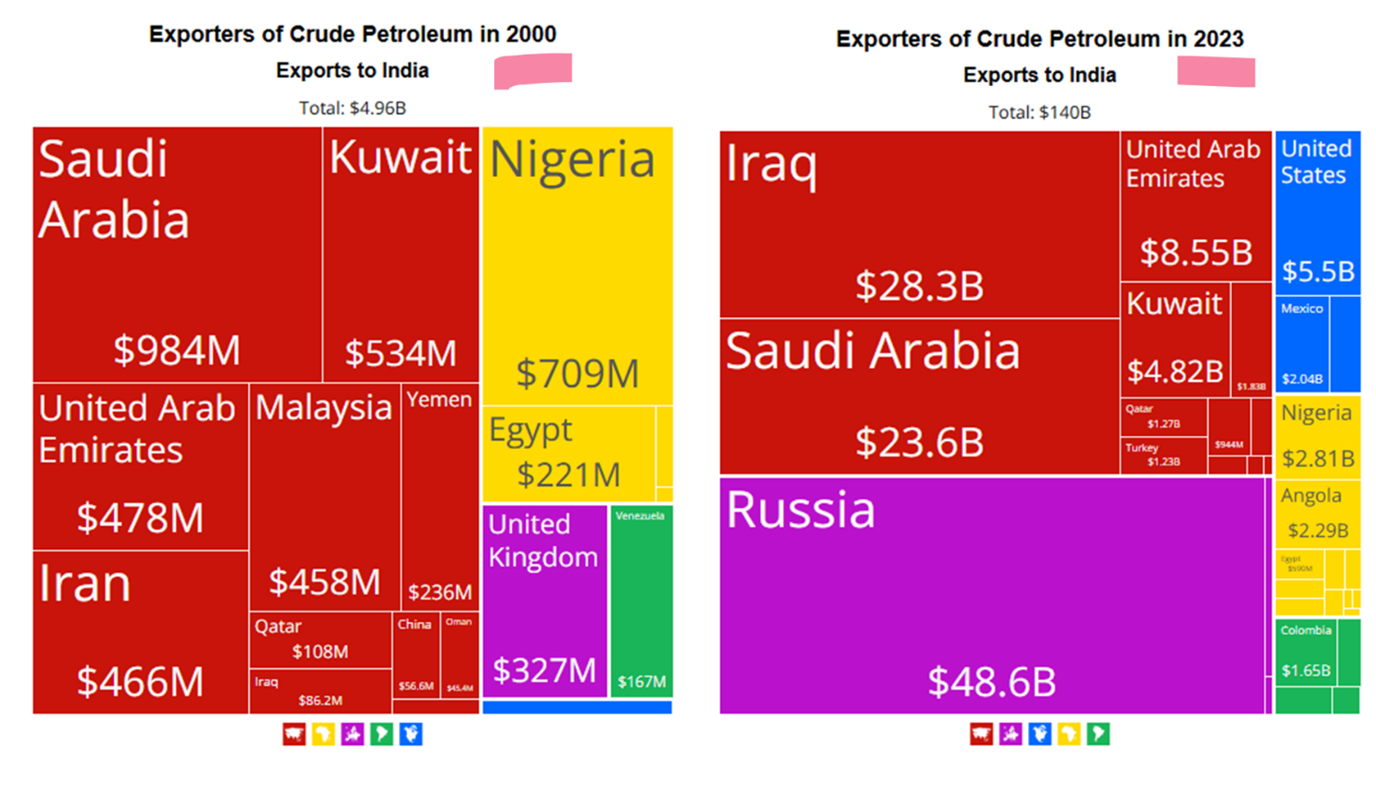

India’s oil imports

In 2023, India imported $140 billion worth of crude oil, 72% of which came from Russia ($48.6 billion), Saudi Arabia ($23.6 billion), and Iraq ($28.3 billion). This was nearly 30 times the value imported in 2000 as per Figure 5.

Figure 6 – Indian oil imports from various countries (Source: Observatory for Economic Complexity).

While oil imports were at $5 billion in 2000, India was also more highly exposed to oil from the Middle East, with about two-thirds of the imports from the region. The diversification of India’s oil sources is a strategic shift in ensuring its energy security.

Given that under the BAU scenario, India would still import 80%+ of its oil requirement by 2047, estimated to be 8 MMbpd, the strategic imperative is clear: diversify oil sources and seek new and reliable partnerships.

India’s coal imports

According to the observatory for economic complexity, a similar trend is noted in Coal. In 2000, $1.5 billion worth of coal was imported, ~1 billion of which was sourced from Australia. Other countries from which India obtained coal were South Africa ($210 million), Indonesia ($140 million) and China ($130 million].

Fast forward to 2023, and the value of coal imports ballooned to $39 billion. While Australia still commanded the largest source of coal for India, valued at $14 billion, its share had shrunk to 35%. Notable new coal sources were Russia ($4.7 billion), United States ($4.61 billion), and Canada ($1.29 billion).

In a BAU future where ~40% of India’s total coal requirement (2047) – estimated at 1,806 MMt – is imported, diversification and co-operative partnership are crucial.

Indian gas imports

For natural gas, India was a relatively small player in 2000, when its natural gas imports totaled $260 million, making it a mere drop in the $85-billion gas trade at the time. At that time, its major supplier countries were Saudi Arabia ($137 million), Iran ($28.7 million), Kuwait ($25.6 million), and Qatar ($18.8 million) – all Middle East countries.

While in 2023, India imported 100 times more gas at $24.8 billion, its major suppliers are still Middle Eastern countries; Qatar at $9.71 billion, the UAE at $5.74 billion, and Saudi Arabia at $2.29 billion. The U.S. has also made inroads in the Indian market, supplying $1.54 billion worth of gas.

India has been more successful in diversifying its supply sources for oil than for gas and coal. Despite this success, in the IESS’s “Self-Reliant” scenario, 55-65% import dependence is noted for oil, gas, and coking coal by 2047. Even under a BAU scenario, an overall 40% import dependency across its energy supplies is noted, this tiger will still need a lot of friends.

Closing thoughts – lessons for India’s energy transition

The IESS 2047 outlines pathways for India to balance economic growth, energy security, and emissions reduction. While acknowledging gaps in modelling infrastructure costs, advanced nuclear tech, non-energy emissions, and energy prices, the outlooks are useful in gauging future demand under different scenarios.

Hydrocarbon resources still have a role to play in the “self-reliant” scenario, and more so in the “business as usual” scenario. The report emphasizes electrification, domestic supply expansion, and efficiency as pillars of India’s energy transition. As India hinges its energy security on aggressive policy support for renewables, it will no doubt be studying countries’ experiences with cleaner grids. The recent electric grid blackout experiences in Spain, which impacted France and Portugal, the near-miss collapse of the UK grid, and the about-face coal plant restart in Germany when faced by the “dunkelflaute” will be studied by India’s energy experts as case studies.

India still has more than a two-decade runway to 2047 – enough time to learn from the mistakes of others and strengthen its relationships across the Arabian sea and Asia-Pacific. Celebrating 100 years of political independence is a big deal, and it should not come with ugly surprises related to energy security.

(Kasse Gbakon– BIG Media Ltd., 2025)