We have said from the beginning that BIG Media’s goal is to provide objective, unbiased, spin-free journalism. But this was never and will never be an easy mark to hit. One of my earliest articles, Nudge and the uneasy pursuit of context and objectivity, on nudges spoke about bias. It generated a great deal of commentary from readers. Even my closest friends told me that being unbiased would be close to impossible.

They were right; unbiased, spin-free news is almost impossible.

Almost.

One of our biggest challenges came very recently, when we took on an article that seemed so controversial that the first editorial impulse was not to write it at all. What followed was a discussion of the need to not take a side, to not become a tool of propaganda and adhere uncompromisingly to our principle of objectivity. The article in question was Analysis of the Pfizer COVID vaccine trial for children aged 5 to 11, which is about the Pfizer vaccine trial on children. The story around the challenges of writing this article is itself a lesson.

The problem

When I proposed this article be written, the editor was concerned that we should not write something that would act to inflame an already emotional issue. Vaccination, vaccine passports, vaccine mandates, safety and ethics have caused societal strife – even on the ethical side as discussed in the article Mounting COVID frustration is no reason to abandon fundamental principles. He was worried we could make a bad situation worse, and moreover play into the propaganda machines of either the vaccination or anti-vaccination camps.

My response was that we had to write the article. If our entire purpose is to add reasoned and unbiased analysis to the difficult issues of the day, how could we not rise to the challenge? After all, the more difficult and sensitive the issue, the more that reasoned and careful analysis is needed.

I was also pretty sure that the data would speak for itself, and that I was capable of analysing and reporting the data objectively.

However, I did not know that even the conversation to this point had already affected me.

The effects of editorial advice on the writing

In researching the article, I discovered evidence to these four points:

- The Pfizer children’s vaccine trial indicated relatively high effectiveness (91.3%).

- The trial sample size was small. Efforts taken to mitigate this included immunobridging.

- None of the trial participants experienced severe adverse vaccine effects, but the trial was small enough that we might not expect to see any. This limitation is not uncommon in drug trials, but it is significant.

- Children aged 5-11 experience far less severe outcomes, particularly death, from COVID. Rendering the need for the vaccine (if we assume we only vaccinate children for their own direct benefit) to be relatively smaller for children than for any other age group.

These results were objectively obvious from the data. However, I remembered the editor’s advice and was psychologically primed to avoid offering anything that could be considered opinion. This affected my internal willingness to directly comment or provide an opinion on points 3 and 4.

But my level of affect went even further.

The original chart, the one I submitted, and what was finally submitted

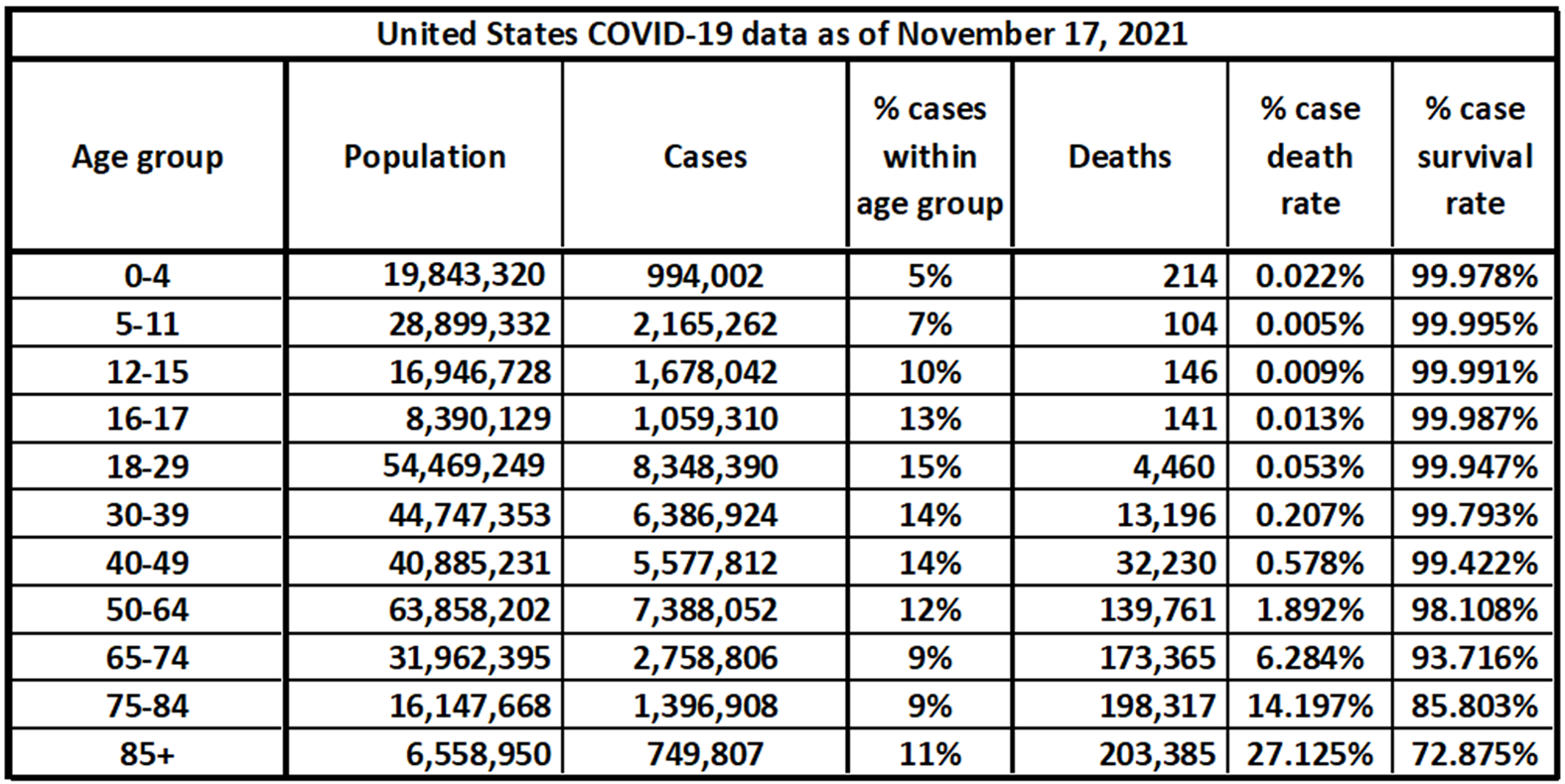

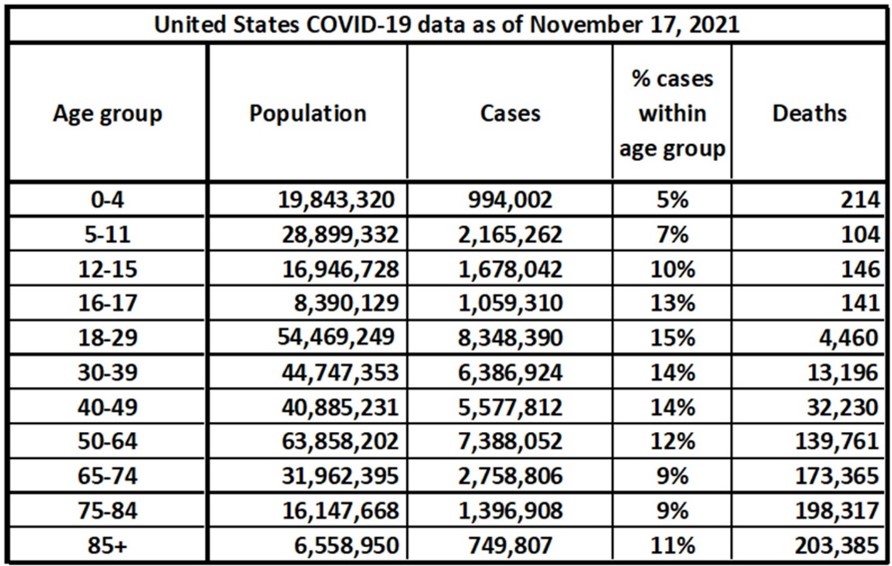

Point 4, above, is a factual element. It cannot be interpreted any other way than how it is stated. I built a chart from the demographic data, and it originally looked like this:

But I remembered the editor’s advice about spin, and I worried that the chart would somehow cross the line. In a remarkably poor moment of reasoning, I told myself that readers could work out the case death and survival rates if they wanted to. So I killed the last two columns, and submitted this chart:

When my editor saw the first draft of the article, he immediately asked that the case death rate be added. He made this request without knowing I had already done the calculation and discarded it. So, the final, published, version of the data chart reverted to the one I had originally created. The discussion of bias had affected my judgment, which was correct the first time. I had edited myself into a mistake.

Original conclusions, suggested conclusions, and final conclusions

Making conclusions is usually the most perilous element of a news article, for here we may go beyond summarizing data and enter the realm of interpreting what the data means. In both science and journalism, conclusions should be parsimonious and limit themselves to what the data supports. At the same time, to omit stating an obvious and important conclusion may also introduce bias. I was reluctant to provide any colour on the facts of the low mortality rates for children or the small study size. This was the first draft of the final paragraph in the article:

Follow-up study on vaccinated children, the vaccine effectiveness, the relationship of comorbidities to outcome, and any reported adverse effects is warranted.

This is the paragraph as suggested by the editor:

The statistically miniscule risk of severe outcomes (to date) among young children who contract COVID-19 should be at the forefront in any policy-related discussion of vaccination in this age group. There is insignificant data on adverse reactions, and any long-term side effects of both infection and vaccination are, by definition, unknown. Follow-up studies are required to better assess the suitability of COVID vaccination of children.

I did not think that the word “miniscule” was objective, and I also felt that the editor’s suggested statement about the need for follow-up study was too strongly worded. I knew that it was not uncommon that trials would be too small to find adverse effects. It is normal to engage in follow-up surveillance of vaccine effects. At the same time, the point was important. With this in mind, I rewrote the paragraph as follows (final conclusion paragraph):

The statistically small risk of severe outcomes (to date) among young children who contract COVID-19 should be at the forefront in any policy-related discussion of vaccination in this age group. The biggest objective concerns in regard to safety and adverse events for children are the small sample size and study time in the Pfizer trial. Although no significant adverse events were reported, this should be studied further.

Finding our way back and letting the data speak for itself

In the end, the final article was better, more accurate, meaningful, and unbiased through co-operative work between the writer and editorial team. The data spoke for itself.

A never-ending challenge

Eliminating – or, more realistically, minimizing – bias, proves to be very challenging. It is easy to either allow passion and perspective to run away with our objectivity, or to self-edit ourselves away from stating important facts … which itself is an act of bias. Even looking at bias can affect objectivity through acts of inclusion or omission. It is the editorial version of the uncertainty principle where we cannot determine the position and momentum of an electron at the same time.

This difficulty will never disappear. We have no innate virtue that makes us superior on issues of objectivity. We can, however, elevate our efforts in working together respectfully but with firm resolve to minimize spin.

We will not allow ourselves to hide from an issue out of fear that we cannot rise to the challenge. As Tennyson said, we must, “Strive to seek, to find, and not to yield” to either fear or subjectivity.

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2021)