No one looks forward to failing, or to enduring an accident. We want to succeed in every aspect of our personal and professional lives and with our goals. We believe these things are important to achieving success. And it is difficult to argue with that desire. Everyone loves a winner, and we all like to win. But not every missed goal – in the short term – is necessarily a terrible thing, and not all accidents are failures, or the result of negligence or foolishness. Some accidents may even be a triumph of a different kind.

I blew out my right ankle rock climbing three weeks ago, and I am left with the question: is the accident best characterized as a failure, or is it possible to view it as a well-disguised stepping stone to success?

If it is possible to view my accident as a success, what evidence do we have that my attitude is rational as opposed to delusional?

Oh, the irony

On Sept. 25 of this year, I published this article In search of the zone on the sharp end[1] about an outdoor rock-climbing trip to the Skaha Bluffs in British Columbia. In the article, I spoke of my mental attitude during climbing, and a search for the zone, of flow state; that timeless place of optimal experience and performance.[2]The zone is a place where nothing matters but what we are absorbed in. Achieving flow is essential to the optimal experiences in sports, sex, emotional experiences, parenting, and even in leadership.

The narrative of the article was my mental state as I approached this climbing trip. I needed to set aside feelings of dissatisfaction and being under-challenged in my life at that time, and enter a state in which I could safely and enjoyably climb on lead. The article ends with an account of how I was able, at times, to release my fear and anxiety, and climb in a higher state of being.

Less than a month later, I was climbing indoors and sustained a serious injury to my right ankle. Was this irony after speaking so recently of finding the zone and climbing fearlessly? Let me tell you more, and you decide.

I was on a 5.11+ route, near the limit of my ability, though I had ascended to the crux – or hardest part – of the route quite easily. The crux was interesting. My right foot was up about as high as my flexibility would allow (perhaps neck height) on a large, rounded hold. Both hands were high and to the left on another rounded hold. I needed to push up explosively, mantling with both arms, then pushing with my right leg, leave just my left hand in mantle and reach up with my right hand to the next hold above me. I needed to move up and laterally, and I needed the muscles of my arms, legs, and core to each execute a series of contractions powerfully and in a particular order. I fell. I tried again. I fell again. I moved my right foot around, I tried to use it as a heel hook. I tried a lot of things. Several times I touched the next hold with my right hand, but could not quite grip it.

I asked myself, “Am I trying hard enough? Am I exploding the way I need to? Am I letting go and allowing myself to succeed?” In essence, I was asking if I was in flow. I consulted with my climbing partner and told him that I would make one more attempt.

I closed my eyes, calming down, finding confidence and relaxation, preparing for an ultimate effort, but doing it in a state of happiness and peace. I launched into motion, executing the complex set of movements … and, in a white flash of pain, my ankle snapped sideways.

After my partner lowered me to the ground and I crawled away from the wall, I asked myself how I should feel about what had just happened.

The injury

It appears that the accident caused a number of soft tissue injuries to my ankle, the worst being a potential rupture of both the superior and inferior peroneal retinaculum. The retinaculum act as a sort of tunnel or straps that hold the peroneal tendons in place, running behind the ankle. The peroneal tendons are critical in stabilizing the ankle.[3]My peroneal tendons now move (or sublux) across the ankle instead of staying behind it, which creates pain and stability issues.

The path forward is an MRI, which is imminent, and potential bracing, surgery, or physiatry. In the meantime, I am able to cycle, swim and lift weights. Climbing is not possible at present.

It is not that we like to fail, it is that we do fail and what happens afterward

In describing flow, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, does not guarantee that it will come with victory. He points out that flow may accompany significant pain. The victory is the optimal experience – how it feels – and how we have performed as well as possibly could in a peaceful, fully engaged mindset. How we feel is a choice.[4]

We should never seek failure, or mistake celebrating failure as a desire to fail. We want to succeed, but failure is inevitable. Mistakes happen. Accidents happen. If we engage in a mindset where mistakes and failures are viewed negatively, we invite denial, anxiety, and possibly the repetition of the mistake. Companies such as Google, Intuit, Gore, and others celebrate mistakes so that their employees may learn from them. By celebrating the mistakes, they feel that errors are reported quicker, and solutions and innovations come more freely.[5]Various writers have pointed out that accepting and learning from mistakes lead to many other benefits, including: learning more from our experiences, accepting and making peace with the past, obtaining a more realistic viewpoint of success, encouraging real, maximum effort, and to learn to persevere.[6] [7] [8]

Feeling shame, fear, and potentially engaging in a cover-up are not things we should encourage in ourselves, in others, or in our organizations. To avoid that, we must take a more positive view of mistakes. By accepting failures as opportunities to learn or grow, we position ourselves best to make use of them positively.

Psychology – is this positivity over a bad outcome delusional?

Readers might ask themselves at this point if taking such a positive view of accidents or failures is delusional. The continuous improvement aspect aside, we may ask if there is evidence to support positive thinking in such scenarios. Or are we indulgently fooling ourselves? Research from sports psychology supports positive thinking in achieving flow, but what other evidence do we have to support positivity?[9]

There are three implied psychological-physiological claims in viewing mistakes positively. The claims as questions to be examined:

- Can we control how we feel? Can we truly decide to take a positive attitude?

- Does feeling positively have a measurable effect on health?

- Does pushing positivity affect success?

Can we control our attitude?

Psychologists have studied this and invented repeatable empirical procedures to assess the level of anxiety in test subjects. They also have best practices for introducing positive or negative thought stimulus, in the form of verbal or mental imagery, and measure changes in the level of anxiety of these test subjects. This is not to be confused with the approach in the fictional movie “A Clockwork Orange”, in which subjects are forced to watch scenes of horrific violence. A study by Hirsch et al is worth discussing.[10]It is orderly, involves a baseline meditation, the presentation of a negative scenario, a period of focused attention, a post scenario meditative period, followed by a categorization of thoughts and finally a statistical assessment. The number of negative thought intrusions during each meditative period was recorded. The time period for each phase was five minutes. Hirsch was trying to demonstrate not only whether positive thoughts were important but whether there was a difference in importance between positive imagery and positive verbalization.

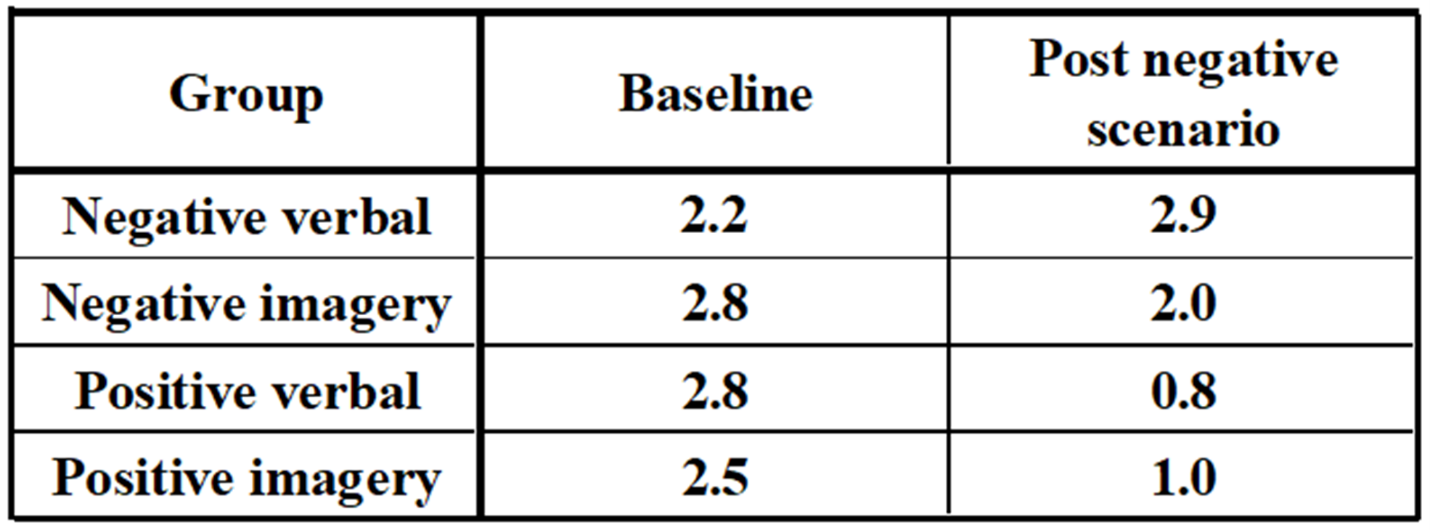

Her study’s results are summarized in the table below, where the values given correspond to levels of anxiety (represented by the average number of thought intrusions) during meditation. In the study, there are four groups, each given a negative scenario to consider and a period of follow-up focused attention. The groups varied by the style and content of their focused attention. Those groups were:

- A group instructed to perform negative verbal reinforcement or self-talk

- A group instructed to focus on negative imagery

- A group instructed to perform positive verbal reinforcement or self-talk

- A group instructed to focus on positive imagery

The effect of positive thoughts is assessed by comparing, for each group, the difference in the average number of negative thought intrusions between the baseline period or the post negative scenario period. The results show that a focus on positive words or images resulted in less negative thought intrusions.

Table 1: Results adapted from Hirsch et al on the effect of focused positive or negative imagery on the average number of negative thoughts for each subject group.[11]Lower numbers are associated with more desirable results. Positive focus of either style had a measurable effect on the number of subsequent negative thought intrusions.

Another study conducted over a period of weeks was conducted on groups of individuals diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder. This study followed a week of focused thinking to see what the results of longer periods of positive or negative thought training would be. This study yielded comparable results to Hirsch et al, and further showed that it did not matter what the content of the positive focus was, so long as it was positive.[12]

Does a positive mental attitude affect health positively?

There have been myriad studies relating positive mental attitudes to health. The answer to the question above is complicated and was best parsed out in a meta-analysis by Segerstrom and Miller of 300 studies.[13]They delved into perceived versus objective stress and various measures of immune function and effect from stress. Results on the subjectivity of stress were unclear, which is not directly supportive of the thesis of this article.

Their most unequivocal findings were:

- Short-term or acute stress, such as fight or flight situations, created positive effects on the immune system.

- Chronic, or long-term stress showed detrimental effects on the immune system.

Other research supports the idea that it is chronic stress that is harmful to human beings. The argument is that our physiological systems are designed to manage and recover from acute stress, such as danger from predators. What is argued to be harmful to us is when the stress (or negativity) persists for extended periods of time. We are not, apparently, evolved for that.[14]

Does a positive attitude affect success?

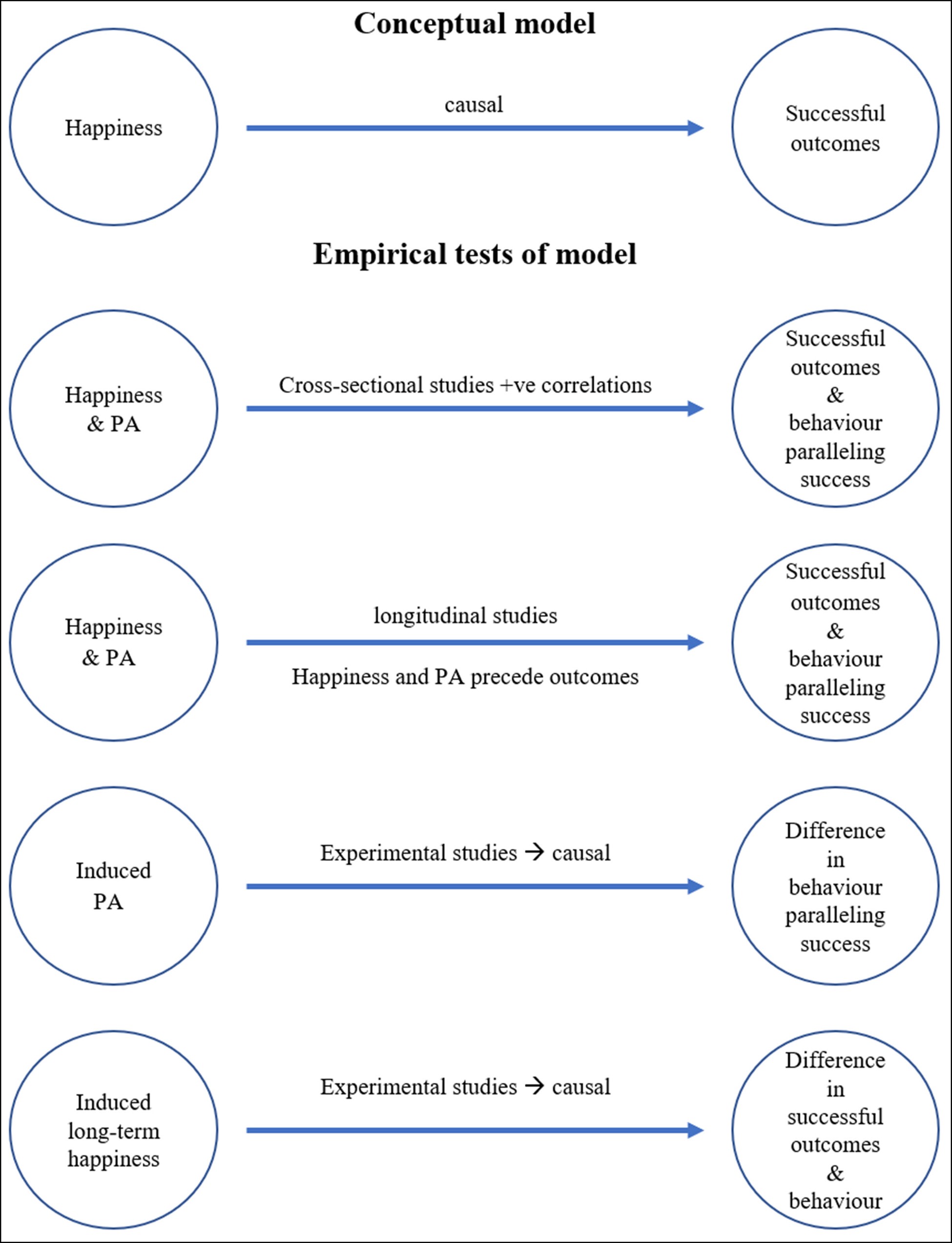

Considering this question likely brings to mind the conundrum of the chicken or the egg. Studies of happiness and success run the risk of a causality problem. Did the happiness lead to success or did the success lead to the happiness? This problem was undertaken meta-analytically by Lyubomirsky et al by examining both observational and empirical studies of varying length.[15]The figure below breaks down their analytic method. To determine if happiness creates successful outcomes, they examined studies that had the following properties:

- Cross-sectional, or a snapshot in time that showed a correction, but not causation. This study is done observationally.

- Longitudinal, which is also merely observational, but over an extended period of time, and was capable of determining the sequence of events. Did success come first or did happiness?

- Experimental, in which subjects faced interference. They were coached on their mental attitudes. Two flavours of experimental study were examined.

The meta-analysis considers something called positive affect (PA). PA is the idea that “Positive moods and emotions lead people to think, feel, and act in ways that promote resource building and involvement with [goals].”[16]Confidence, optimism, effective coping, and prosocial behaviour are all related to PA.

Design of experiments to determine whether happiness or the positive affect (PA) of happy thoughts leads to success. A combination of observational and empirical tests was required in the meta-analysis to overcome issues of causality. Figure adapted from Lyubomirsky et al.[17]

This meta-study found abundant evidence that happiness and success were correlated. Although there were less longitudinal studies performed (likely because they require a longer period of study), this style of analysis supported that happiness preceded success, supporting its causality.

The experimental studies, incredibly, involved inducing happiness or PA in test subjects. The induction would be through a variety of means not dissimilar to coaching and focusing, as in the analysis given for controlling mood. There was evidence in many of the empirical studies examined in the meta-analysis that induced happiness, and PA had a positive measurable impact on success.

Why?

Greater success and health from happiness and a positive outlook (an attitude that has been shown to be somewhat controllable) are thought to be a result of many factors, each of which is linked to happiness and PA through the meta-analysis. It should be noted that the degree of statistical support for these relationships varied. These factors including the following:[18]

- Prosocial behaviour

- Improved coping

- Better immunity

- More positive perceptions and judgement of others

- Greater physical activity and energy

- Improved flexibility and originality

- Healthier choices

- Better negotiation and conflict resolution

- Better self-perception

Get real

In no sense do any of these peer-reviewed studies claim that all or most disease will be cured by feeling positive, that the people who succumb to illness did so as a result of their poor attitude, or that my torn connective tissue will magically heal because I think constantly of unicorns and lollipops. Nor do the studies suggest that thinking positively will erase all anxiety or guarantee success for everyone. The evidence is statistical, not deterministic, and in no way claims, or could claim, that happiness and positive outlook are the only important variables.

These studies do, however, suggest that a more positive outlook may help in some statistically measurable way with the relative health, stress levels, and success of populations.

And it feels better.

Crawling away from the wall

In the immediate aftermath of my climbing injury, I was not thinking about psychological studies.

There were two processes going on, perhaps not quite at the same time. One was practical; I wanted to evaluate what I knew was a serious injury. Could I go home, or should I go immediately to the hospital? That was important, but I also was processing and attempting to control how I felt about the accident.

I looked inside … and I felt good. I knew that I had tried hard, that I had put forward a maximum effort, and not in fear, but in a state of calm focus. It was also clear that, while I was acting at the edge of my ability, my actions were not reckless. I felt no regret. Since then, I have considered the incident and while I am not happy that I hurt my ankle, I look forward to mindful recovery and my next foray into flow. The failure of my ankle was not a failure of self.

Pursue the next best moment

Was my positive attitude delusional, regardless of the psychological studies I have brought forward? We all know that being our best self, acting, feeling or being in our optimal state, is not a guarantee of success or a shield against misfortune. We cannot control everything that happens. We can, however, control how we respond to events. We can control how we feel about them, and what we do next. Our very best moments may sometimes precipitate failure, and how we respond to adversity might just lead us to the next best moment.

[1] Hunt, Lee, 2021, In search of the zone on the sharp end

[2] Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, 1990, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

[3] Peroneal Tendon Injuries, Shoreline Orthopaedics

[4] Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, 1990, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

[5] Stewart, Henry, June 8, 2015, 8 companies that celebrate mistakes

[6] Collins, Sam, 2020, Radio Heaven: One Woman’s Journey to Grace, ISBN 979-8655217546

[7] Bell, Poorna, 2017, 11 Reasons Why Failure Is Essential For Self-Development, Huffington Post, December, 2017

[8] Arruda, William, 2015, Why Failure Is Essential To Success, Forbes, May 14, 2015

[9] Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, 1990, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

[10] Hirsch, Colette, et aal, 2015, Delineating the Role of Negative Verbal Thinking in Promoting Worry, Perceived Threat, and Anxiety, Association for Psychological Science, V3(4) 637-647

[11] Hirsch, Colette, et aal, 2015, Delineating the Role of Negative Verbal Thinking in Promoting Worry, Perceived Threat, and Anxiety, Association for Psychological Science, V3(4) 637-647

[12] Eagleson, Claire, et al, 2015, The power of positive thinking: Pathological worry is reduced by thought replacement in Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Behavior Research and Therapy V79 (2016) 13-18

[13] Segerstrom, Susan, and Gregory Miller, 2004, Psychological Stress and the Human Immune System: A Metanalytic Study of 30 Years of Inquiry, Psychol Bull. 2004 Jul; 130(4), 601-630

[14] Sapolsky, Robert, 1998, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers: An Updated Guide to Stress, Stress Related Diseases, and Coping. W.H. Freeman, ISBN 9780716732105

[15] Lyubomirsky, Sonja, Laura King, and Ed Diener, 2005, The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Behavior Research and Therapy, V 78 March 2016, 13-18

[16] Lyubomirsky, Sonja, Laura King, and Ed Diener, 2005, The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Behavior Research and Therapy, V 78 March 2016, 13-18

[17] Lyubomirsky, Sonja, Laura King, and Ed Diener, 2005, The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Behavior Research and Therapy, V 78 March 2016, 13-18

[18] Lyubomirsky, Sonja, Laura King, and Ed Diener, 2005, The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Behavior Research and Therapy, V 78 March 2016, 13-18

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2021)