On June 23, Bill C-36 was given first reading in Canada’s House of Commons.[1] Concerning hate crime, speech, and propaganda, this bill proposes amendments to the Criminal Code and the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA). The federal government claims that the bill is being proposed to help reduce the rise in hate crimes and make online spaces “safe.”[2]Concerned citizens may reasonably ask if this bill will effectively reduce and redress hate crime, or if it will be a new form of freedom-reducing censorship with the potential for misuse and frivolous claims Or if the bill may bring about elements of both.

We will examine the amendments the bill proposes and some arguments for and against its adoption.

What does this mean in its simplest form?

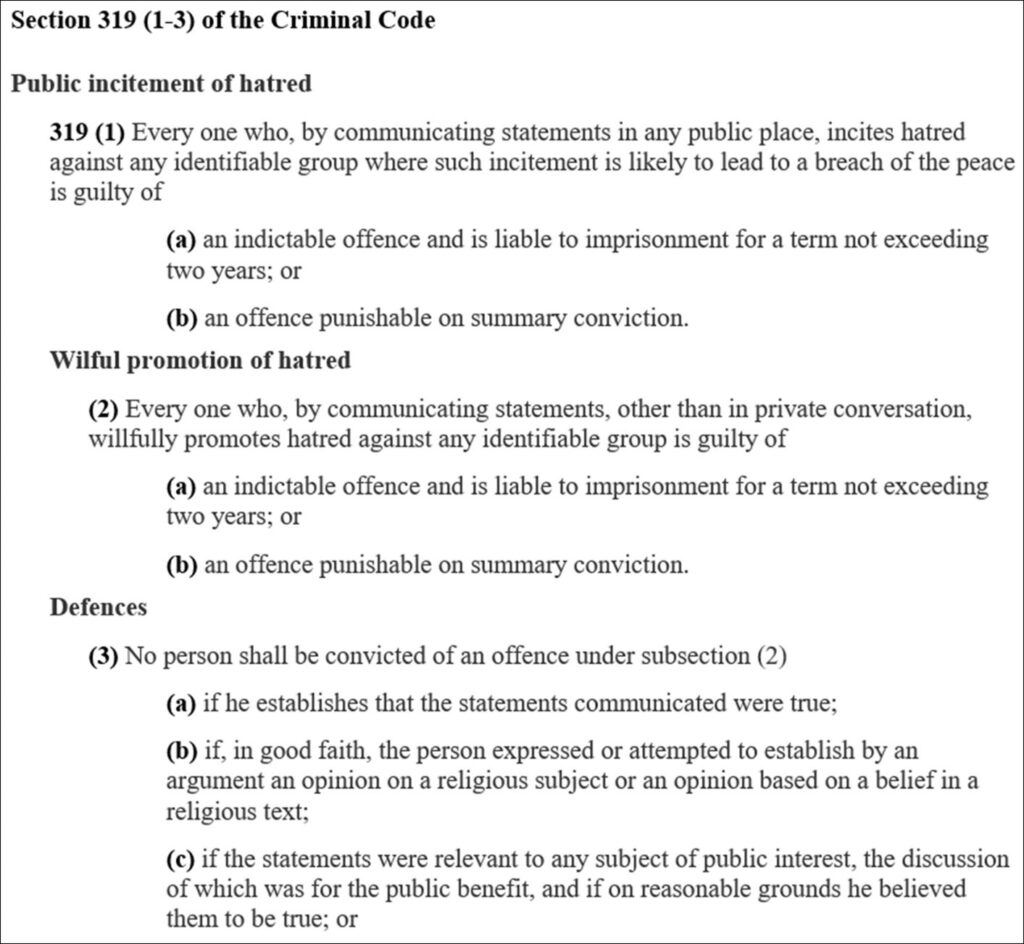

Hate crimes and complaints in Canada are currently addressed only in the Criminal Code, specifically Section 318 and 319. Section 318 deals with the advocacy for genocide, and we shall omit it from this discussion, focusing on section 319. The elements of Section 319 (1-3) are shown below. The Code outlines the offences, (1) inciting hatred likely to breach the peace (law) or (2) willfully promoting hatred. Potential offences go through the legal system and are subject to legal process and defences, including defences laid out in statute, one of which is that what was communicated is true.[3]

Section 319 (1-3) of the current Criminal Code

319 (1), inciting hatred leading to a breach of the peace may refer to immediate danger. Hate crimes may additionally (or instead) be charged as offences such as assault, harassment, defamation, or uttering threats outlined elsewhere in the Criminal Code.[4]Section 319 is the only current avenue where the crime is treated specifically as a hate crime.

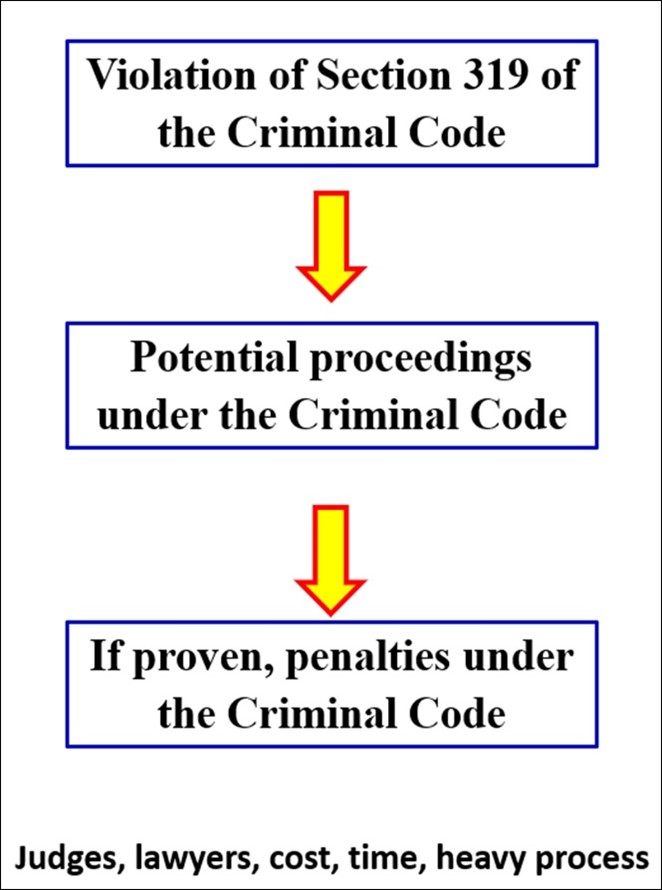

Illustration of the current legal structure regarding (non-genocidal) hate crimes in Canada.

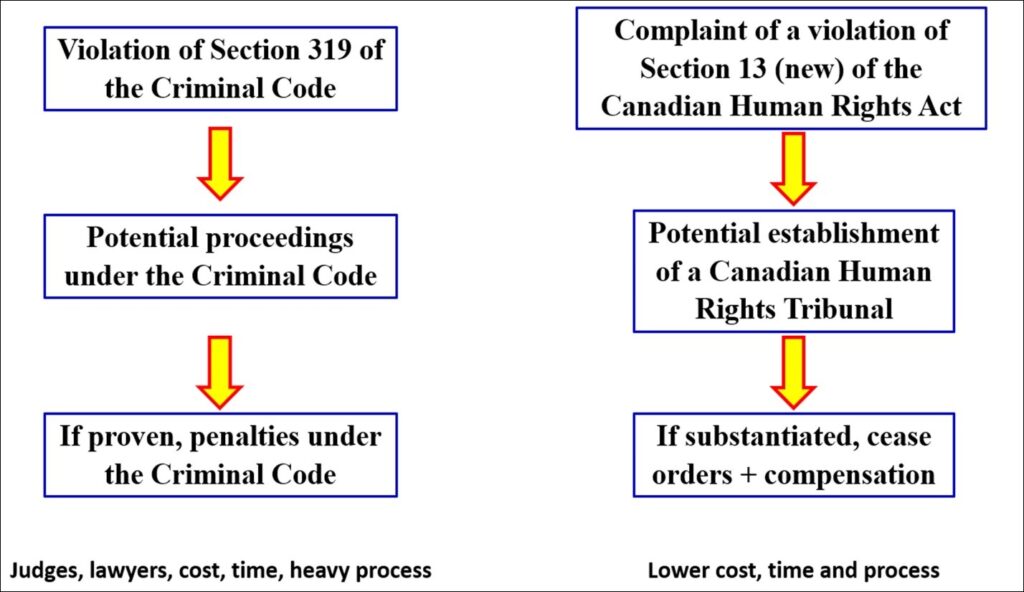

Bill C-36 proposes changes to the definition of hatred and to the Criminal Code, but these changes are arguably immaterial. The most important changes in the bill (with perhaps one element of the Criminal Code to be discussed in the section under censorship) are the amendments to the CHRA. These amendments include, in Section 13, the communication of hate speech – including online communications – as a discriminatory practice. Parties can make a formal complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Commission. If the commission finds sufficient merit in the complaint, it may then form a Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT, or Tribunal) to hear the case. The CHRT is adjudicated by members of the legal profession but does not follow the same level of formalities as court cases under the Criminal Code. Certain legal defences – as in 319 (3) – that are available to defendants in a criminal case, such as truth, are not necessarily available in a tribunal.

As below, Bill C-36 creates two avenues for redress of potential hate crimes. The new avenue, through the CHRA, allows individuals to protect themselves or others from harm through their complaint. They can, essentially, pursue their own justice within the framework of the act. This capability appears to be the most important element of the bill.

Illustration of the legal structure that Bill C-36 proposes. There are now two legal avenues,

one of which allows individuals to make complaints.

There is precedent

There was previously a (2002) Section 13 of the CHRA dealing with hate speech, but this section was repealed in 2014.

The key section of the repealed 2002 Section 13 dealing with hate speech read:

- (1) It is a discriminatory practice for a person or a group of persons acting in concert to communicate telephonically or to cause to be so communicated, repeatedly, in whole or in part by means of the facilities of a telecommunication undertaking within the legislative authority of Parliament, any matter that is likely to expose a person or persons to hatred or contempt by reason of the fact that that person or those persons are identifiable on the basis of a prohibited ground of discrimination.[5]

This section was criticized by some as too vague and overreaching of the rights of free expression.[6]

The new Section 13(1) of Bill C-36 reads:[7]

13. (1) It is a discriminatory practice to communicate or cause to be communicated hate speech by means of the Internet or other means of telecommunication in a context in which the hate speech is likely to foment detestation or vilification of an individual or group of individuals on the basis of a prohibited ground of discrimination.

These sections bear similarities and subtle differences. They both have as their basis a “prohibited ground of discrimination.” The old section uses the language of speech that “is likely to expose a person or persons to hatred or contempt” while the new section uses the language that the hate speech is “likely to foment detestation or vilification of an individual or group…”

This language is remarkably similar; but Bill C-36 includes an important clarification, 13 (10) [8]

(10) For greater certainty, the content of a communication does not express detestation or vilification, for the purposes of subsection (9), solely because it expresses mere dislike or disdain or it discredits, humiliates, hurts or offends.

This clarification is meant to address frivolous complaints and set the legal standard of the complaint somewhere above hurting another person’s feelings. Lawyers and citizens will likely argue whether the old section 13 and the new section 13 are significantly different. There is also a similar clarification amendment in 319 (8) of the Criminal Code section of the bill.

Support for tribunals

The inclusion of hate through Bill C-36’s amendments to the CHRA creates a new facility for complaints about hate communications. Readers may feel reasonably optimistic about the ability of citizens to protect themselves from this kind of abuse. Lower costs, simpler mechanisms, and potentially quicker timing make the use of tribunals a welcome tool for citizens concerned about hate communications.

As Justice Minister David Lametti said, the bill, “will allow anyone to take action if they experience online hate.”[9]A feeling of control may be argued to be helpful to victims of hate communications.

The desire to reintroduce hate communications to the CHRA has been happening for some time, with the House of Commons Justice Committee tabling a proposal for a new Section 13 on June 17, 2019.[10]

Concerns about tribunals

The inclusion of hate communications in the CHRA amendments creates a new facility for complaints about hate crimes. Readers may be reasonably concerned that the relative ease and reduced legal structure of a tribunal may disadvantage defendants unfairly.

Lametti claims that the bill does not, “target simple everyday expressions of dislike or disdain that pepper everyday discourses, especially online.”[11]Some may fear that this will not be the case, and freedom of expression will be jeopardized.[12]What happens when or if Bill C-36 is passed fully will be a matter of legal process and interpretation, and the minister’s statement of intent will be irrelevant.

Peter Jacobsen and Nadine Touma take aim at the process in tribunals in their article “Truth is not a defence.” They suggest that tribunals may lack “expertise and clinical objectivity” needed and that the “accused has to fend for him or herself” in a process “that lacks the presumption of innocence and the requirement that the case be proved beyond a reasonable doubt.”[13]They also point out the 2013 Supreme Court Decision on The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission v. Whatcott[14]and the lack of legal defences, such as the truth, in the CHRA.

The Whatcott trial is often cited by critics of the CHRA and its tribunals. In the Whatcott trial, the lack of legal defences was discussed, with this said about a CHRA case:

“… the Charter did not mandate an exception for truthful statements in the context of human rights legislation.”[15]

Considering the length and expansiveness of the Whatcott document, this point may be an example of cherry picking. This particular passage does not mean that the truth could never be used as a valid defence, but it did suggest that it might not be. It is not specifically provided for in the CHRA. In any case, the CHRA’s lack of specific defences such as those provided for in Section 319 (3) of the Criminal Code is concerning and should be addressed.

Perspective

These criticisms of the tribunals are difficult to evaluate. They may be hyperbolic and overly fearful. Or they may prove to be justified. Moving outside the careful and evolved system of processes of the Criminal Code to the less strict and more ad hoc system of the tribunals is troubling to many.

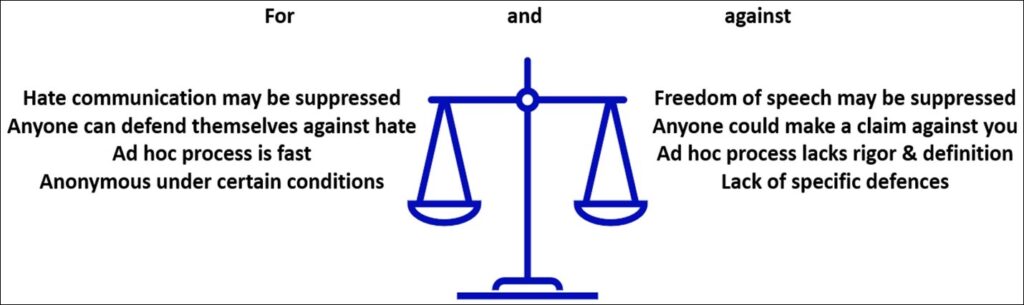

Chart summarizing arguments for and against Bill C-36’s Section 13 amendments to the CHRA

Relevance of timing

Bill C-36 was given first reading on the day Parliament adjourned, which leaves both its fate and the motivation for its introduction in question. Increases in reports of racism against Asian Canadians[16]and Muslims[17]have brought hate crimes to the attention of the media and the public. It could be argued that hate crimes are part of a new availability cascade that the Liberal government is responding to, and perhaps attempting to take advantage of.[18]

Such an argument is, however, irrelevant for two reasons: first, hate crimes are a real problem, and, second, the motivation or alleged motivation of the introduction of Bill C-36 does not matter; only its content matters.

Censorship and freedom

Any law infringing on free speech is, by its definition, censorship. The debate over what thoughts, images, or expressions should be suppressed was around when it was the responsibility of the Roman censors. Despotic regimes throughout history have had – and some still have – punishing and oppressive systems of censorship.

The debate that Bill C-36 will bring is an important one. Crimes of hate are important, and Canadians should expect protection under the law against them as they would any crime. However, when we are discussing a potential crime of expression, the correct balance of freedom and responsibility may not be so clear cut.

In its very act of protecting against hate communication in Section 13 of the CHRA, Bill C-36 enacts censorship. Readers will rightfully ask if this is justified.

Globe and Mail writer Andrew Coyne pointed out an element of censorship inherent in a section of Bill C-36 that we have yet to mention; proposed amendment 810.012 of the Criminal Code.[19]Coyne points out that in this section someone may use the law to stop (through a peace bond) a potentially hateful communication before it happens:

“A person may, with the Attorney General’s consent, lay an information before a provincial court judge if the person fears on reasonable grounds that another person will commit an offence motivated by bias, prejudice or hate based on race, national or ethnic origin, language, colour, religion, sex, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or any other similar factor.”[20]

Coyne suggests that this was an egregious over-reach and is the real “bad news” from Bill C-36. Perhaps, but it should be pointed out that Section 810 of the Criminal Code allows peace bonds to be issued against someone where there is strong reason to believe they will commit specific crimes such as violence against a child.[21]Now, hate crimes, including communication, will be included. Is it justifiable to propose the interception of hate communication as if it is equivalent to physical assault? The argument for this amendment appears to be inadequate.

Social media get a pass

It should be noted that the bill continues the treatment of online media providers as mere conduits. That is, the service provider is not held accountable for hate speech that they may host. They are simply moving data from one place to another, without responsibility for its contents. This is in Section 13, (6-8) of the proposed amendment to the CHRA.[22]

Summary

On the one hand, Bill C-36’s greatest change is that it allows everyday people to bring complaints of hate communications to the CHRA. Tribunals may be formed, and they may seek relief from hateful communications. A certain power of relief is given to victims.

On the other hand, Bill C-36 enables a return of Section 13 and tribunals, and a potential for frivolous claims to be undertaken under less stringent legal processes. A new burden with questionable defence may be placed upon defendants. And a similar burden may be placed on the freedom of speech.

This trade-off needs careful consideration. Much angst might be avoided if other amendments were included in Section 13 of the CHRA that would ensure fairness to the defendants. Specific defences such as those in 319 (3) of the Criminal Code should be considered.

References

[1] Parliament of Canada First Reading June 23, 2021, https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-36/first-reading

[2] Stober, Eric, June 23, 2021, Liberals introduce bill to fight online hate with Criminal Code Amendments, Global News

[3] Department of Justice Government of Canada Justice Laws website. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/section-319.html

[4] Proctor, Jason, June 13, 2020, The Difficult history of prosecuting hate in Canada, CBC News

[5] Government of Canada, CHRA version of section 13 from 2002-12-31 to 2014-06-25, https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/H-6/section-13-20021231.html

[6] Saint-Cyr, Yosie, June 14, 2012, Section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act Repealed!?

[7] Parliament of Canada First Reading June 23, 2021, https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-36/first-reading

[8] Parliament of Canada First Reading June 23, 2021, https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-36/first-reading

[9] Stober, Eric, June 23, 2021, Liberals introduce bill to fight online hate with Criminal Code Amendments, Global News

[10] Gyapong, Deborah, June 18, 2019, Justice Committee recommends reinstating Section 13 to combat online hate

[11] Stober, Eric, June 23, 2021, Liberals introduce bill to fight online hate with Criminal Code Amendments, Global News

[12] Stober, Eric, June 23, 2021, Liberals introduce bill to fight online hate with Criminal Code Amendments, Global News

[13] Jacobsen, Peter, and Nadine Touma, May 30, 2013, Truth is not a defence, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

[14] Jacobsen, Peter, and Nadine Touma, May 30, 2013, Truth is not a defence, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

[15] Supreme Court of Canada Judgements, 2013-02-27, Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission v. Whatcott

[16] Nagai, Tracy, April 25, 2021, What is a hate crime? Lawyers across Canada define the term, Global News

[17] Stober, Eric, June 23, 2021, Liberals introduce bill to fight online hate with Criminal Code Amendments, Global News

[18] Stober, Eric, June 23, 2021, Liberals introduce bill to fight online hate with Criminal Code Amendments, Global News

[19] Coyne, Andrew, June 24, 2021, Section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act is back. And that’s not even the bad news, The Globe and Mail

[20] Parliament of Canada First Reading June 23, 2021, https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-36/first-reading

[21] Department of Justice Government of Canada Justice Laws website. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/section-810.html?pedisable=true

[22] Parliament of Canada First Reading June 23, 2021, https://parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-2/bill/C-36/first-reading

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2021)