The 2021 UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26), which started Oct. 31 and runs through Nov. 12 in Glasgow, will see further debate on the international scale about climate change and what can be done about it worldwide. The goals for the event include: securing commitments for global net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, protecting communities and natural habitats, mobilizing finances from developed nations to help developing countries reduce CO2 emissions, and to work on the co-operative international structure necessary to achieve these goals.[1]

Many readers will recognize that climate and CO2 emissions have firmly entered the zeitgeist, with many jurisdictions throughout the world declaring that we are in a “climate emergency”. The United States has not yet declared such an emergency, although New York City, the state of Hawaii, and other jurisdictions within the country have.[2]COP26 has seen widespread political and news media support for climate action.

A problem as complex as CO2 emissions and their effect on the climate has many facets, including issues of trust, co-operation, technology, political posturing, and finance. Each of these factors can be further broken down. Even on the subject of energy sources, discussions and arguments can be examined concerning the fate of fossil fuels, carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), the role of nuclear, wind, solar, or hydrogen power, electricity, and lithium batteries. And while each of these matters and a list of others are important, no single event such as COP26 will resolve them. We will be discussing these issues long into the future.

Looking at a global problem such as climate change and the ambitious – perhaps overwhelming – goals of COP26, readers may wonder if anything positive and actionable might come out of it. Yes, in a way, for the climate emergency has become an economic emergency. And perhaps an economic opportunity.

This article breaks down some of the broad economic incentives in acting against climate change by looking at how two of the biggest emitting regions in North America – the state of Texas and the Canadian province Alberta – are incentivized to lower CO2 emissions. For them, to some degree, the climate emergency has certainly become an economic emergency. This analysis provides a rational expectation for large scale, near-term change.

An apology to reduction

This article takes several reductive steps for brevity, and to be consistent with current language around climate change. First, when we reference CO2 emissions, we mean metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent of all greenhouse gases. This article is CO2-centric. There are other greenhouse gases that are factors in global warming, but this article focuses solely on CO2. Last, we treat CO2 emissions as connected directly to climate change. Global climate is affected by many factors, including natural processes and CO2 levels. We do not debate this within this article. So, take the role of CO2 emissions in climate change as accepted for the sake of this discussion.

A rational look at climate change action: game theory

Game theory is often used to study the rational economic choices of multiple interdependent actors. In this article, Prisoner’s dilemma and vaccination[3] BIG-Media used game theory to break down the choice of vaccinating for COVID-19. Climate change similarly benefits from such treatment. Because climate change is a global problem, the solution of which requires co-operation worldwide, its study through game theory has been extensive.[4]

The difficulty in tackling climate change is high in part because not every region in the world is equally incentivized; resources available and costs of solutions vary from country to country. At the heart of the problem is the fact that CO2 is a byproduct of many wealth-producing activities. Producing more CO2 produces more wealth.[5]Reducing CO2 emissions either reduces wealth directly in that the activities that produce the CO2 are curtailed, or indirectly as costly technological innovations are applied to reduce the CO2 emitted from the wealth-producing activities.

The tragedy of the commons and future costs

Set against the rational self-interest of CO2 production is the cost of climate change, which at present, is largely a future cost. There are many conflicting elements on the topic of climate change, and the idea that consequences are in the future is an important one. Game theorists treat the health of Earth’s ecosystem as a diminishing resource, which becomes scarcer with CO2 emissions. From an economic perspective, this is a tragedy of the commons, where the problem becomes ever worse, and the value of solving it becomes ever higher as the ecosystem is brought closer and closer to collapse.[6]

At some point, all agents will be highly motivated to solve the problem of climate change. However, reaching the point of environmental collapse is undesirable for two key reasons:

- The cost for solution will be higher

- The damage to the ecosystem is undesirable, and some elements of that damage may be irreparable[7]

Co-operation, trust, and free riders

Any evaluation of climate change must consider that it is a global problem. Every region is capable of emitting CO2 and damaging the ecosystem. Everyone is part of the problem. Everyone also benefits from making the problem worse through their CO2-emitting, wealth-creating activities. And everyone will suffer as the ecosystem is damaged.

Because climate change affects everyone and CO2 emissions spread throughout the world, no single actor or group of actors can solve the problem. It is not enough for 10 parties to drastically curtail their CO2 emissions if three other parties increase theirs. Co-operation is essential.[8]

Co-operation is an objective at COP26, in the Paris Agreement, and in all other climate change summits and agreements. A big problem with co-operation is the issue of trust; will some groups act as they say, or will they attempt to be “free riders”? Lack of trust regarding climate change action is a scenario similar to that of the prisoner’s dilemma, and creates the rational tendency to act selfishly.[9] [10]

Inequities and wealth transfers

Not every region faces the same costs in lowering its CO2 emissions, and not every region has the same capacity to pay those costs. One of COP26’s four key goals is to secure a minimum of $100 billion dollars yearly from wealthy nations to help poorer nations enact climate change mitigation strategies.[11]This wealth transfer can be rationalized because of the global nature of the problem, but also requires trust that any contributed sum will be used as intended, and that wealthy nations contribute fairly.

Wealth transfers to combat climate change do not have to be between nations; they can also be between industries within a nation. Some game theorists suggest that it is rational for there to be a transfer payment between greener industries to help CO2-intensive sectors such as hydrocarbon industries reduce emissions.[12]The political ramifications of this suggestion are considerable.

How a climate emergency becomes an economic emergency

It may seem to readers that little has been accomplished to combat climate change. The political and economic issues implied in this narrow discussion are substantial, and are far from the only ones that need to be addressed in order to combat climate change. Is there any reason to expect significant and effective action in the near term?

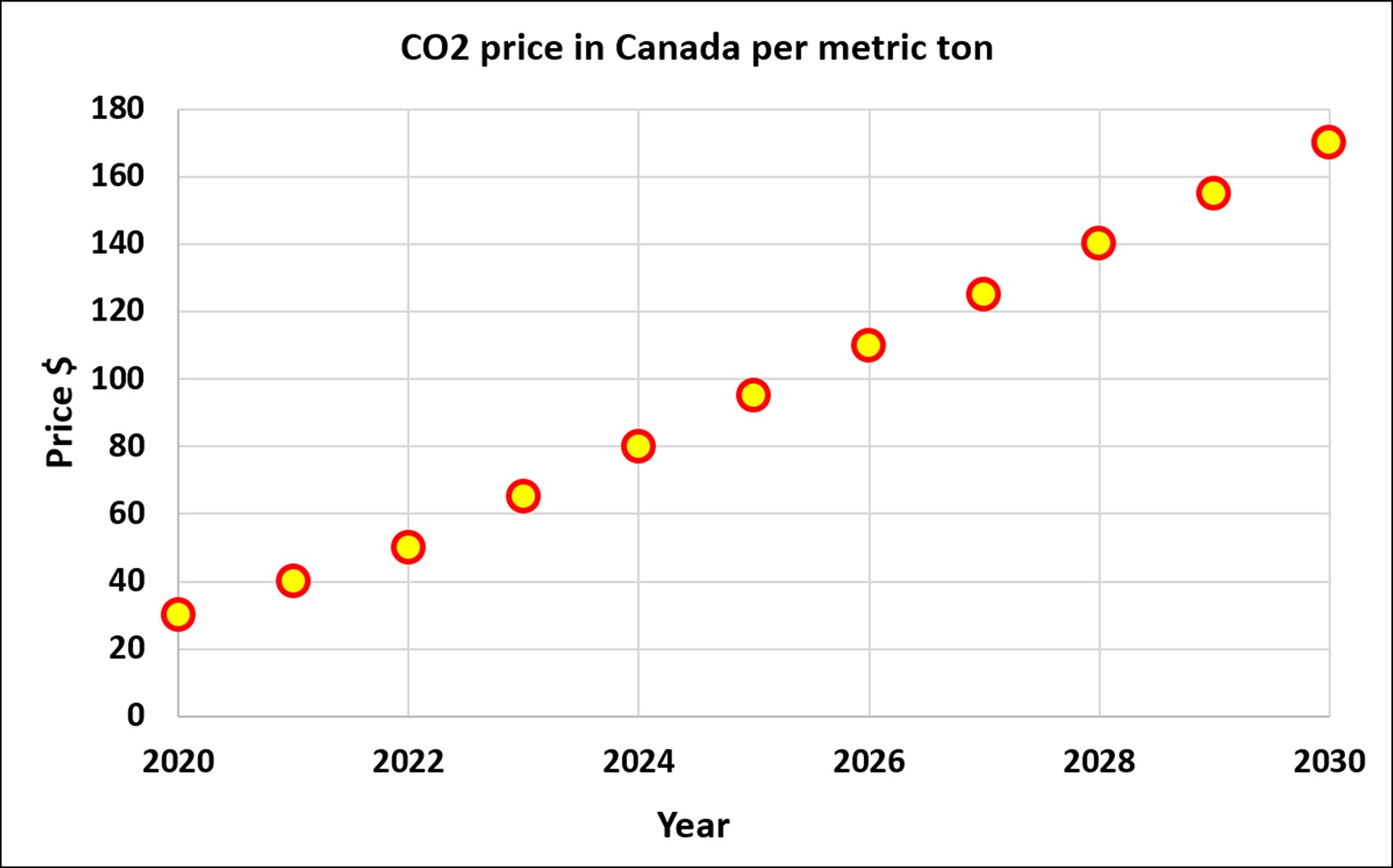

Yes, because some nations have created material, internal economic motivation to act. Carbon taxes have been enacted in many countries to create an economic incentive to mitigate CO2 emissions and combat climate change. In some cases, these carbon taxes are scheduled to become so onerous that the climate emergency has become an economic emergency. Canada, for example, is scheduled to see carbon taxes, levied per metric tonne of CO2, rise to more than four times its current level by 2030.[13]These tax increases are significant enough to create an exigent need to reduce CO2 emissions.

Canada’s carbon tax, increasing from $30 per tonne in 2020 to $170 per tonne in 2030.[14]

Not all countries have enacted carbon taxes. The U.S. has no current carbon tax, nor does Russia, Australia, or most of the continent of Africa. China has initiated a CO2 emissions trading system, but its final implementation and effect remain to be seen.[15]

The U.S. has a CO2 sequestration tax credit in Section 45Q of the US tax code.[16]This tax credit is for $50 per metric tonne of permanently sequestered CO2. The U.S. is considering implementing border taxes on countries that attempt to “free-ride” the climate change issue. Countries that do not enact CO2 mitigation programs could see their goods taxed upon entry to the U.S.[17]

The story in the Lone Star State

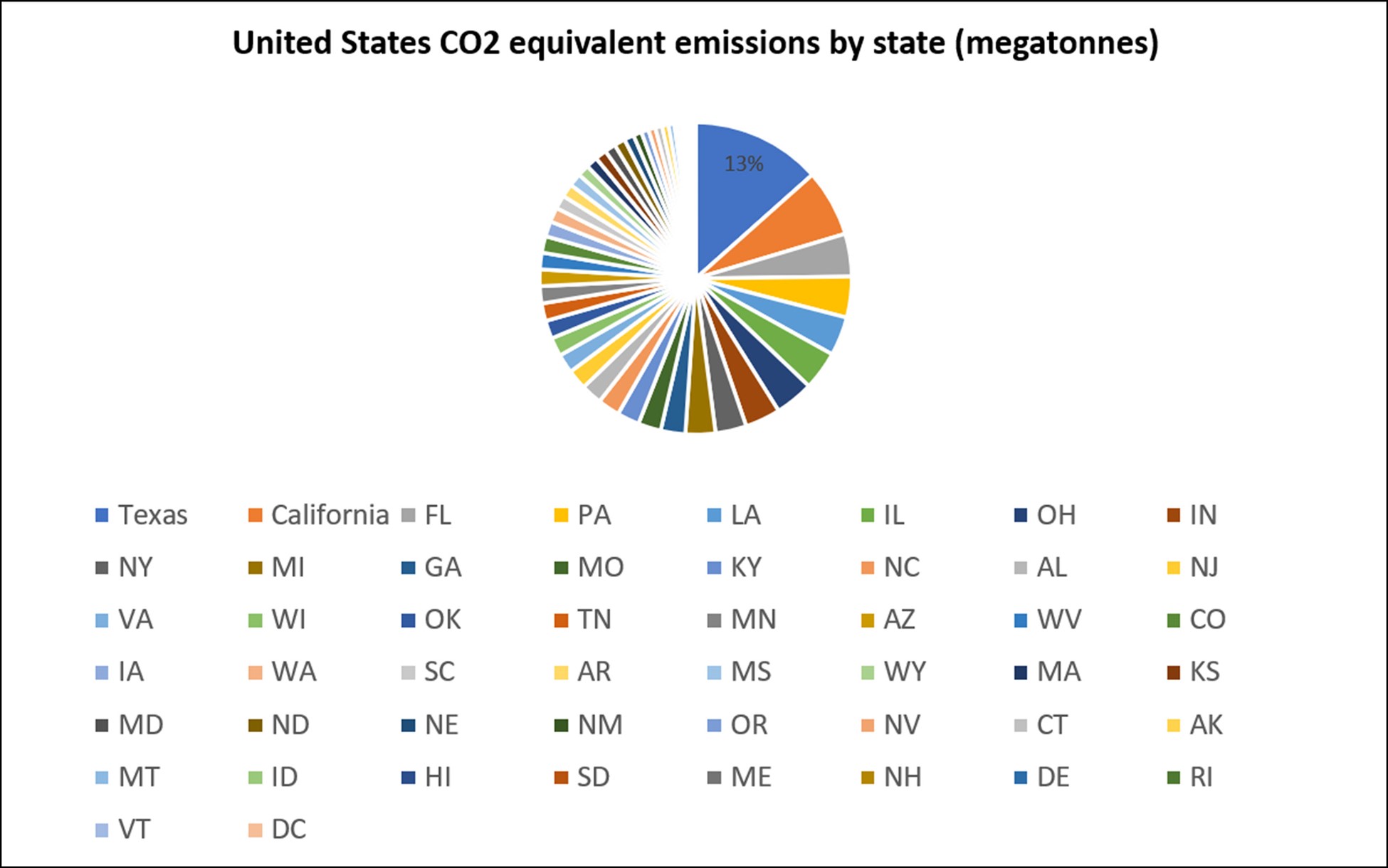

Texas is the centre of oil and gas production and refining in the U.S. As of 2018, it produced 13% of the nation’s CO2 emissions.[18]This puts Texas in a unique position within the country regarding climate change mitigation, and the economic effect of such efforts. Rather than using taxes as a form of punishment to motivate action, the tax credit is a positive incentive to emit less, and is more analogous to the transfer payment between industries mentioned in our earlier discussion of game theory.

In 2018, Texas produced 13% of the CO2 emissions in the entire U.S., largely from oil and gas activities.[19]California is the second largest emitter.

For context, California (12% of U.S. population) and Texas (9%) are the two most populous of the 50 states.

The 45Q tax credit provides sufficient economic incentive for the development of a carbon handling and storage hub on the Gulf Coast.[20]Much of the CO2 storage will likely occur offshore.

Naive look at the value of CO2 storage

45Q has specific provisions regarding the applicability of any particular project for its tax credit. It is impossible for every tonne of CO2 to qualify. However, let us look at a simple estimate of the total potential tax credit value of the CO2 emissions in Texas.

If the tax credit is $50 per tonne and all 701.9 megatonnes of CO2 emissions in Texas were able to qualify, this would amount to $35.1 billion dollars annually. Even a fraction of this amount is significant incentive to act.

Other industries in the U.S.

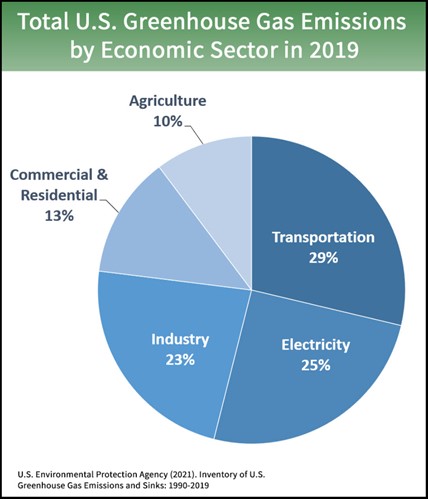

While Texas is the largest emitter in the country, every state emits CO2. Electricity generation produces 25% of the nation’s emissions, while transportation produces 29%, and “industry” produces 23%.[21]Every state where these industries exist – meaning all of them – may have an economic incentive to reduce emissions. There have been discussions that Section 45Q may change; it could be replaced, or the value of CO2 emissions could be increased. Numbers as high as $175 per tonne have been proposed.[22]Changes to the tax credit or the qualification for the credit could materially affect the economic motivation for climate action.

Alberta’s escalating carbon tax

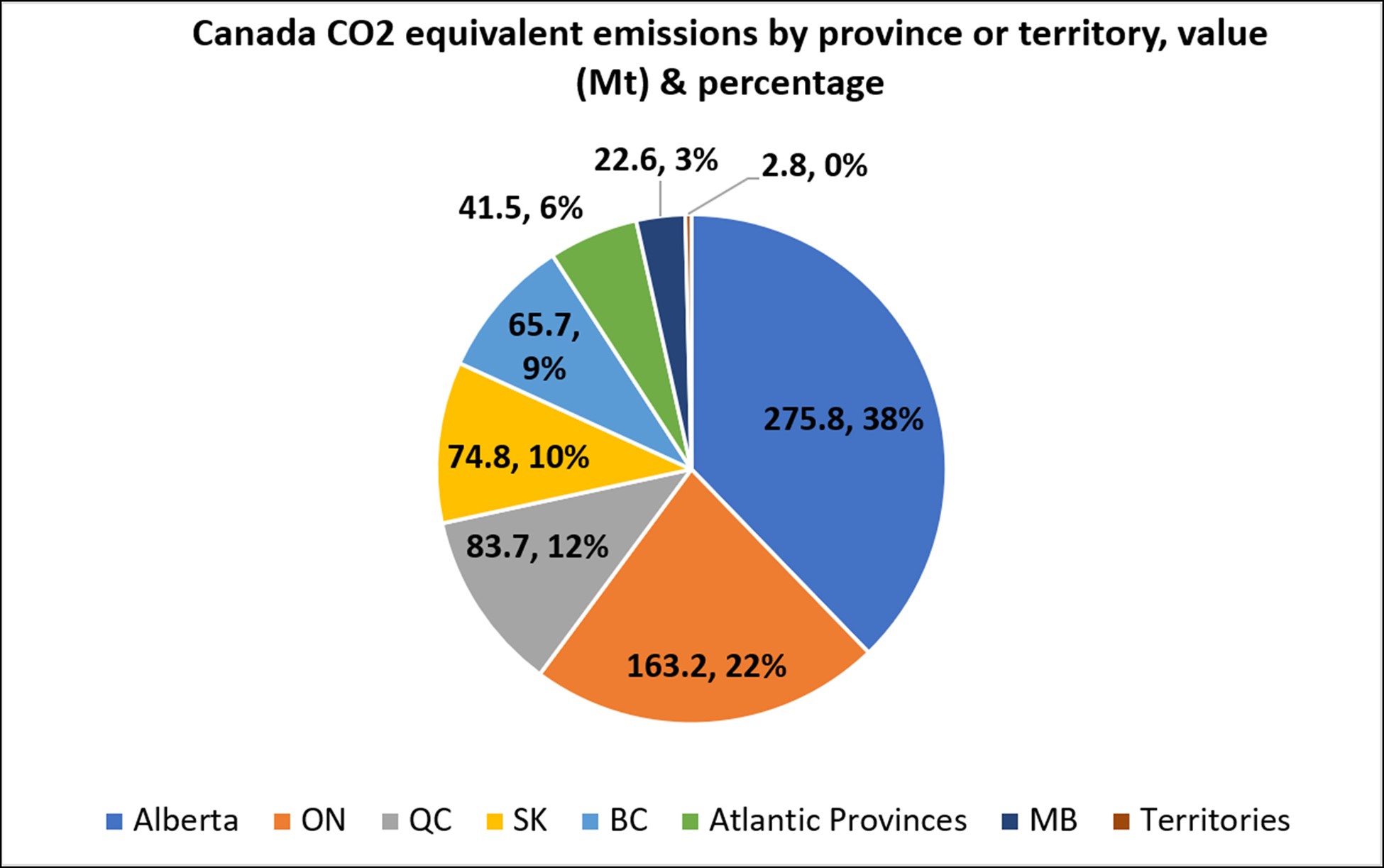

Alberta is in an analogous situation to Texas. It produces 275.8 megatonnes of CO2 per year as of 2019, representing 38% of Canada’s emissions, much of this from the oil and gas industry.[23]Carbon taxes in Canada are $40 per tonne in 2021, but are scheduled to increase to $170 per tonne by 2030. Alberta will therefore have both the greatest challenge and incentive to reduce emissions in the country.

For our discussion of Texas, we made a simple model of the value of CO2 emissions. We can do a similar thing for Alberta, again in a simplified format. If we use the 2019 values for emissions and the 2021 cost of CO2, Alberta’s total carbon cost, if every tonne of CO2 qualified for the tax, would be $11 billion. Readers should note that the simplification applied here are for illustrative purposes. Alberta has its own system of qualification, called Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction Regulation (TIER), that regulates emission pricing.[24]The goal is not to collect $11 billion in carbon taxes but to provide a framework in which emissions will be reduced. Under TIER, large emitters have relative emissions-performance goals that they must reach, or they pay into a levy within the framework, or purchase carbon offsets. TIER’s collected revenue may be used to fund innovative emissions-reducing projects.[25]

Canada’s CO2 emissions by province or territory as of 2019.[26]Alberta is responsible for 38% of the country’s emissions.

Escalating carbon tax creates urgency

Canada’s carbon tax increasing from $40 per tonne in 2021 to $170 in 2030 creates a powerful motivation to act, and act quickly. Let us examine that motivation in the simplest way.

The carbon tax has also been referred to as carbon pricing or carbon cost. Government bodies are applying a cost against emissions. The taxes collected can be used in many ways, including helping to pay for the mitigation itself. The qualification and application of the tax program will be far from simple. Cap-and-trade systems will be used in some regions, and not every industry will be taxed at the same level.[27]These complications make an assessment of the total carbon cost very difficult.

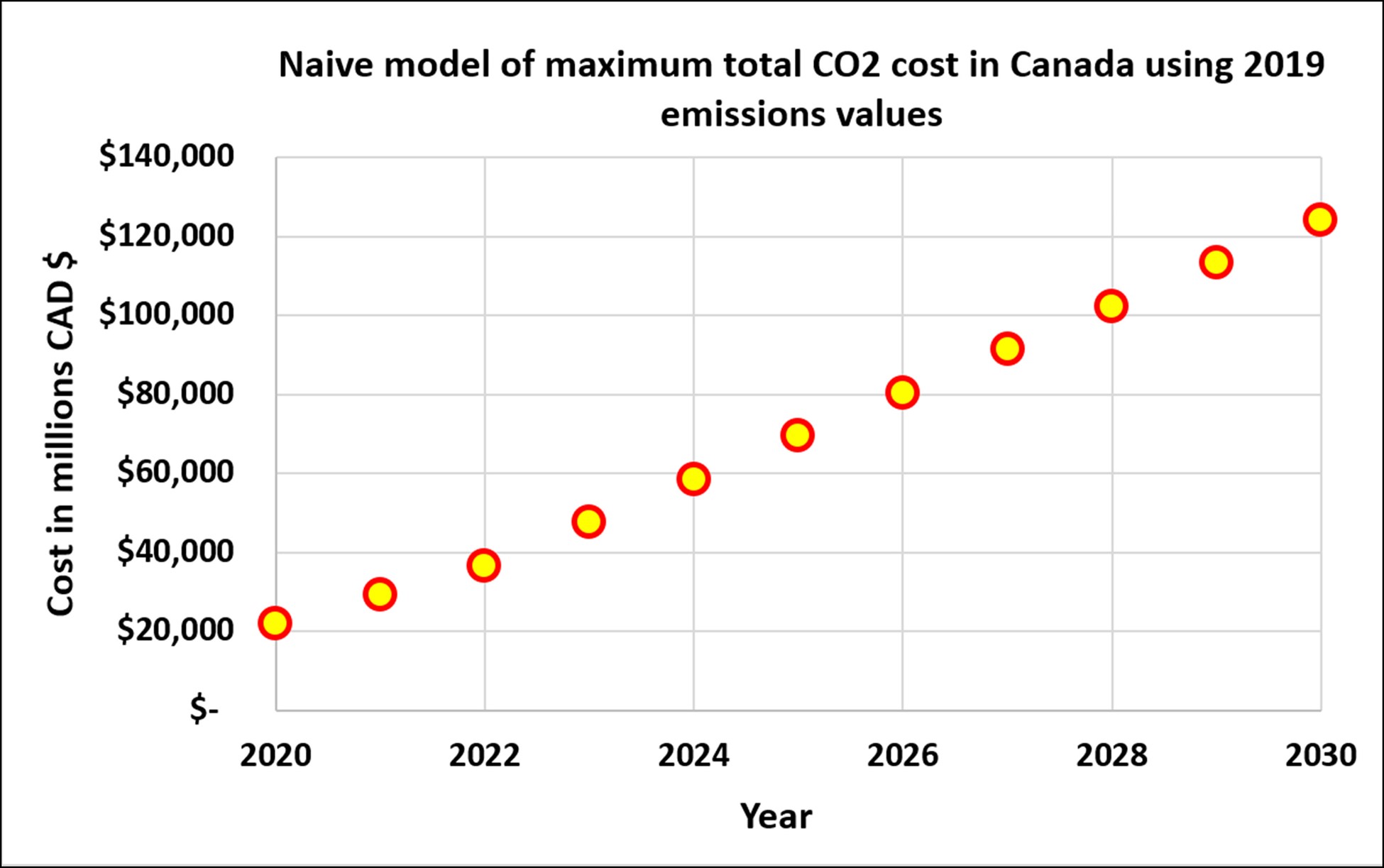

We can, however, make a naive estimate of the carbon cost. The chart below calculates the total cost of CO2 in Canada under the following assumptions: all CO2 emissions are subject to the escalating tax as scheduled, and we use 2019 CO2 emissions for each year going forward. This second assumption may first appear to make little sense, as the goal is to reduce CO2 emissions. However, since our goal is to show the economic motivation for mitigation, using the 2019 numbers has utility. The projected value of the carbon tax in 2030 is $124 billion dollars. Considering that Canada’s total tax revenue from all sources in 2019 was $771 billion, this is significant and, if actually collected, would likely cause tremendous economic harm.[28]However, this number is illustrative and in no way reflects what taxes would actually be collected. In reality, the carbon tax system is complex with exemptions, offsets, credits, relative industrial benchmarks, and an uneven application. The goal is primarily emissions reduction, and much of the complexity of each jurisdiction’s application of carbon pricing and regulation reflects this.

This level of rapidly increasing taxation and wealth transfer creates urgency to act, but every emergency is also an opportunity. Managed correctly, new industries will rise in response to this economic hammer.

Model of the maximum total CO2 cost in Canada using 2019 emission values and the escalating carbon tax.

What immediate actions should be expected?

The economic drivers will see further development of a carbon capture and sequestration hub on the Gulf Coast. Each industry will approach the problem according to its structure. Transportation emissions reduction will see different strategies from concentrated emitters such as the power industry. Countries with escalating carbon pricing will have a stronger motivation to act quickly.

Alberta, with its high levels of concentrated oil and gas emissions and escalating carbon costs, should logically view the problem as exigent. It appears that the Government of Alberta is acting in accordance with this, and on a very compressed timeline:

In May of 2021, an information letter was released stating that carbon sequestration rights would be issued through a competitive process. On Sept. 9, a request for expressions of interest (EOI) was produced with a deadline of Oct. 12. The official request for full project proposals (FPP) is expected in December, with an unknown due date.[29]

On Nov. 5, the Alberta government released its Hydrogen Roadmap, which might be viewed by readers as a companion piece to the carbon sequestration rights being pushed through so quickly. Alberta’s concentrated oil and gas and power generation industries make such combined initiatives attractive.[30]

These tight timelines are consistent with the Government of Alberta viewing the situation as the economic emergency that it is. Readers should expect significant CCS rights allocations to be announced in early 2022, followed quickly by the news of numerous potential CCS and hydrogen projects.

Interpretation

The climate change issue is complicated. Summits such as COP26 may at first appear to face an overwhelming number of problems and conflicting interests, both economic and political. Even when viewing the problem of climate change through the rational lens of game theory, the issues may seem insurmountable. After all, we are considering a problem that affects everyone – but everyone differently – requires co-operation and trust, and is more costly in the future than it is now. How can we expect immediate, co-operative action?

We cannot answer all of these questions any more than COP26 will. However, there is reason to believe that immediate – perhaps surprising – action to mitigate CO2 emissions will happen in the near term. Carbon tax credits in the U.S. may help spur development of a CCS hub on the Gulf Coast. Escalating carbon taxes in Canada may see numerous carbon sequestration rights awarded in Alberta, followed by significant CCS and possibly hydrogen projects.

As the climate emergency became an economic emergency, complex problems became clearer, and opportunities began to emerge.

Expect change. Soon.

References

[1] UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021, COP26 Goals

[2] Kaufman, Alexander, June 26, 2019, New York City Declares A Climate Emergency, Huffpost

[3] Hunt, Lee, August 30, 2021, Prisoner’s Dilemma and vaccination, BIG Media

[4] Hsu, Shi-Ling, 2013, A Game-Theoretic Model of International Climate Change Negotiations, Florida State University College of Law, Scholarship Repository

[5] Dyke, James, April 13, 2016, Can game theory help solve the problem of climate change? The Guardian

[6] CBC News, Nov 1, 2021, Alberta dedicates $176M in emissions reduction projects through TIER fund

[7] CBC News, Nov 1, 2021, Alberta dedicates $176M in emissions reduction projects through TIER fund

[8] Dyke, James, April 13, 2016, Can game theory help solve the problem of climate change? The Guardian

[9] Dyke, James, April 13, 2016, Can game theory help solve the problem of climate change? The Guardian

[10] Newkirk, Vann, April 21, 2016, Using Game Theory to Break the Climate Gridlock, The Atlantic

[11] UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021, COP26 Goals

[12] Hsu, Shi-Ling, 2013, A Game-Theoretic Model of International Climate Change Negotiations, Florida State University College of Law, Scholarship Repository

[13] Tasker, John, Dec 11, 2020, Ottawa to hike federal carbon tax to $170 a tonne by 2030, CBC News

[14] Tasker, John, Dec 11, 2020, Ottawa to hike federal carbon tax to $170 a tonne by 2030, CBC News

[15] C2ES Center For Climate And Energy Solutions, Carbon Tax Basics

[16] McMahon, Jeff, July 29, 2021, Will Congress Supercharge 45Q—The Carbon-Capture Tx credit—Or Scrap it?, Forbes

[17] Friedman, Lisa, July 19, 2021, Democrats Propose a Border Tax Based on Countries’ Greenhouse Gas Emissions, The New York Times

[18] EIA U.S. Energy Information Administration, Rankings: Total Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 2018 (million metric tons)

[19] EIA U.S. Energy Information Administration, Rankings: Total Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 2018 (million metric tons)

[20] Meckel, T.A., et al, 2021, Carbon capture, utilization, and storage development on the Gulf Coast, Greenhouse Gas Sci Technol. 11: 619-632

[21] United States Environmental Protection Agency, Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions

[22] McMahon, Jeff, July 29, 2021, Will Congress Supercharge 45Q—The Carbon-Capture Tx credit—Or Scrap it?, Forbes

[23] Government of Canada, Greenhouse gas emissions

[24] Government of Alberta, 2020, Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction Regulation

[25] CBC News, Nov 1, 2021, Alberta dedicates $176M in emissions reduction projects through TIER fund

[26] Government of Canada, Greenhouse gas emissions

[27] Future Learn, August 25, 2021, What is Canada’s National Carbon Tax and how does it affect us?

[28] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Details of Tax Revenue – Canada

[29] Coueslan, Marcia, Wade Zaluski, and Brody Loster, 2021, Risk-Based Design of Site Characterization and Measurement, Monitoring, and Verification Plans for Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage Projects, CSEG Recorder, V 46, No. 3

[30] Government of Alberta, November 5, 2021, Alberta Hydrogen Roadmap

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2021)