At the end of an enlightening conversation over coffee with a friend, I found myself in a quandary, facing four refuse and recycling bins. Where was my coffee cup to go? There is an opening for trash, for refundable containers, for mixed recyclables, and for compostables. Is this cup recyclable? If so, which recycling bin does it go into? Or is it trash? Or is it compostable? If it should go into the recycling bin, would it actually be recycled? I have heard that a significant portion of recycling is not recycled at all.[1] An image came to mind of the different bins really just being a façade: four openings all really leading to one big bin – the one going to the landfill.

I was caught between feeling guilt at my wastefulness, shame at my ignorance, and futility that no matter what I did, that coffee cup was going into the garbage. So, I decided to learn more, for, at the very least, my ignorance has a cure.

Scale of the problem

Knowing the scale of things is a good place to start. Although this journey of curiosity began with my coffee cup, it is useful to know about all kinds of solid waste and how much of it we produce.

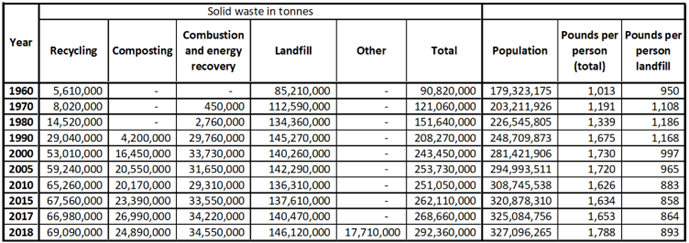

The environmental protection agency (EPA) in the United States attempts to estimate the amount of solid waste managed by municipalities every year. The total amount of solid waste, as of 2018, was more than 292 million tonnes. This amounts to about 811 kilograms (1,788 pounds) of solid waste per person in the country, or just over 2 kg of waste per person per day. The amount that goes into a landfill was estimated at 405 kg per person per year or about 1.1 kg per person per day.[2]That’s a lot of coffee cups.

The per-person landfill amounts appear to have dropped since highs in 1970s to 1990s, but the numbers have levelled off in recent years.

The EPA’s estimates of solid waste totals in the United States.[3][4]

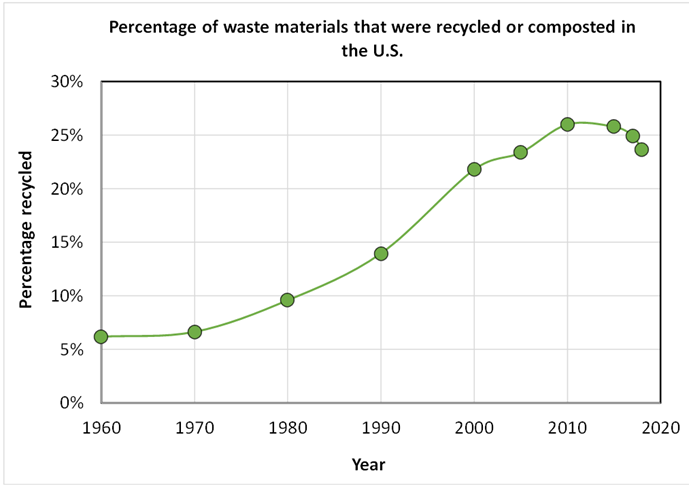

The percentage of solid waste that is recycled or composted rose steadily from 1970 to 2010 before dropping back below 25% in the second decade of this century.

EPA estimates of the percentage of materials that was recycled or composted in the United States.[5]

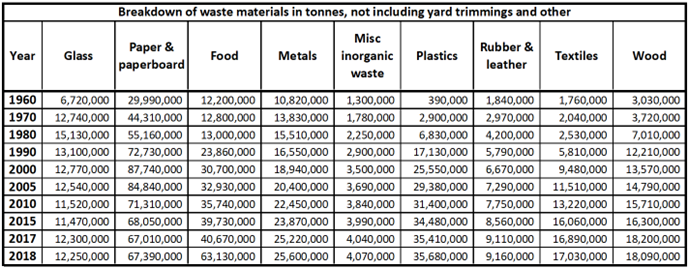

The waste materials are further broken down by material type. Most of those types are shown in the chart below. Plastics make up a significant portion of solid waste in the U.S.

EPA estimates of select material types of solid waste.[6]

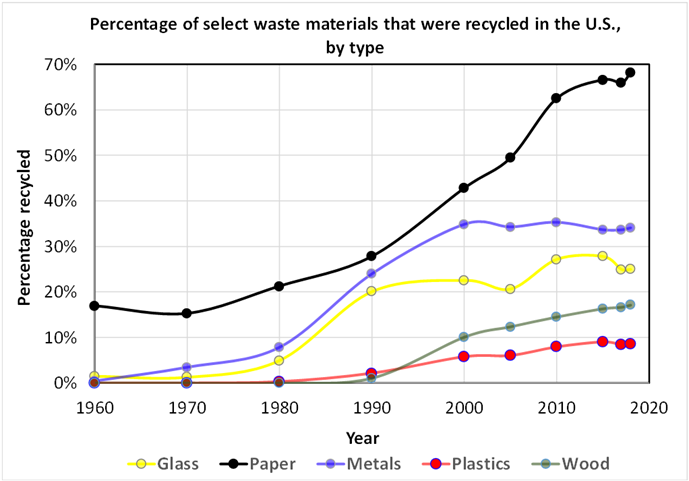

The percentage of recycling can be broken down by material as shown in the chart below. Paper materials appear to be the most successful of the recyclables, with about 67% of all paper waste material being recycled in 2018. Plastics were the least recycled, at 9%. Canada’s recycling profile is very similar to that of the United States, with 9% of plastics in Canada being recycled in 2016.[7]

EPA estimates of the percentage of select materials that are recycled.[8]

Plastic predicament

Plastics are of particular concern to waste management because they persist in the environment for so long, and North Americans are so ineffective in recycling them.[9][10]In 2016, in Canada, 87% of plastic waste ended up in a landfill. Of this plastic, 47% is from packaging.[11]Plastic is a political and environmental bugaboo because it has not only resisted efforts at meaningful recycling, but it has exposed what looks like a charade within our recycling system: much of the plastic that goes into the blue bins is not recycled – it goes into a landfill for reasons we will soon discuss.[12][13][14][15]

My coffee cup dilemma – I am not sure if tossing it in any bin is the right thing to do – is congruous with the plastics dilemma. The dream of recycling is of a so-called “circular economy” in which we would use recycling for most waste.[16]This has not transpired so far, and feelings of futility or ignorance in the citizenry must be ameliorated. Even if the laws of thermodynamics will not allow a costless perpetual recycling world any more than they allow a perpetual motion machine, we can do better. However, honesty and transparency are required, since we will all must participate in order to get anywhere close to such a dream.

Coming back to plastics – if recycled, they can be produced as pellets that can be used by manufacturers to make new plastics products. Given that only 9% of plastic waste is recycled, we must assume there are obstacles to doing this. What are they?

Challenges to recycling and how my coffee cup fits into them

Solid waste management is under provincial jurisdiction in Canada, and is largely handled at the municipal level in both the United States and Canada. This results in an inconsistent set of methods for waste management that resembles more of a potpourri than a single, uniform process. That our waste management problem is dealt with at such a local scale likely fosters a garbage NIMBYism and certainly does not make it easy for individuals to know how their waste should be managed as they travel between cities, states, or provinces.[17]

Setting aside regulatory challenges, recycling is not a trivial operation, and it requires several things be accomplished:[18][19][20][21]

-

- That the materials be sorted and separated

- That the materials be clean and uncontaminated by other materials

- That there be no or limited amounts of dyes

My coffee cup is representative of these requirements: there is dye in it, often it could be dirty, or half full – which would be my fault – and it has a small amount of plastic in it. The plastic makes it difficult to recycle, though it keeps the coffee off my lap … for the most part.

Up to 2018, much of the plastic from Canada and the United States was sent to China and other Asian countries for recycling.[22][23][24][25]To a degree, this made part of our problem seem to disappear, and North Americans may have felt that they were being environmentally responsible. However, sending our garbage to countries with cheap labour and lax environmental laws is not as environmentally heroic as we might imagine.[26] And those jurisdictions were not given an easy task. Much of what was sent was deemed to be “contaminated” because it was not properly cleaned. When that happens, the recyclable materials are sent to the landfill.[27][28[29]It is estimated that as much as 70% of the recyclables sent to foreign countries are not recycled, but are burned or put into a landfill.[30]This may mean that the 9% recycling estimate for plastics is optimistic.

Let us try an example. Consider the tub of coconut oil shown below. This cannot be recycled if it is not cleaned. If the coconut oil gets loose, it could ruin the whole batch of recyclable materials it is packed with. The same goes for tubs of condiments such as ketchup, mayonnaise, and peanut butter. China and several other jurisdictions no longer accept our recycling materials, and we must clean our own peanut butter tubs.[31][32]

Plastic tubs of coconut oil and other food products are difficult to clean and present problems in the recycling process.

Underlying the recycling challenge is a critical question – can it be done economically? Aside from the idea of peanut butter contaminating the whole load is the question of whether the recycled plastic pellets will be cheaper than fresh produced plastic. This will depend on oil prices and other factors including certainty of supply.[33]In a higher oil-price environment, plastic recycling will be more economically viable.

Proposed solutions

One of the proposed solutions to so much garbage is something called extended producer responsibility (EPR). The idea here is that producers take on some of the responsibility for solid waste by reducing packaging, using less dyes, and generally making recycling easier to accomplish. The province of British Columbia has implemented an EPR program.[34] [8] Combine this with a clear knowledge of where my coffee cup should be thrown, and this sounds like a helpful idea. Nevertheless, British Columbia has not yet seen a material reduction in plastic disposal.[35]Critics of EPR methods suggest we must simply use far less plastic.[36]After all, part of the problem with recycling my coffee cup is the thin layer of plastic inside of it.

This packaging (for a soundbar) is an attempt at being more responsible by minimizing the amount of packaging and use of dyes, and might be recommended in an EPR program.

A 2019 Government of Canada report proposes that plastic waste be virtually eliminated by 2030 through massive enhancement in mechanical and chemical recycling as well as incineration.[37]In order to accomplish this, several things would have to happen, including: regulatory congruence, restrictions on what can go into a landfill, financial support for innovations, education of all citizens and the securing of their co-operation, and the creation of stable markets for the recycled plastics. Each of these requirements is challenging to accomplish. Taken as a whole, the idea that this recycling panacea will be accomplished by 2030 is highly unlikely – probably absurd. However, the main point of the study was to lay out the scope of the problem. The report does note the importance of economics. If we cannot practically and economically recycle materials, we will not have a successful program.

Thus, it falls to three questions:[38]

-

- Can we create a regulatory and economic environment for the near-complete recycling of plastics? Canada is a potpourri when it comes to waste management, and investors are unlikely to commit to the required degree without governmental clarity. Political announcements of the elimination of plastics by itself will convince few and solve nothing.

- Will people co-operate with such a proposal, and understand how to co-operate? If we don’t know where to put our plastics, they will not be recycled.

- Will we have the right separation of materials to support this? Individual homes as well as business may need additional types of recycling receptacles.

The likelihood of these three requirements being met in the near future is difficult to assess. Like the EPR initiative, this objective is viewed by many with skepticism.[39]

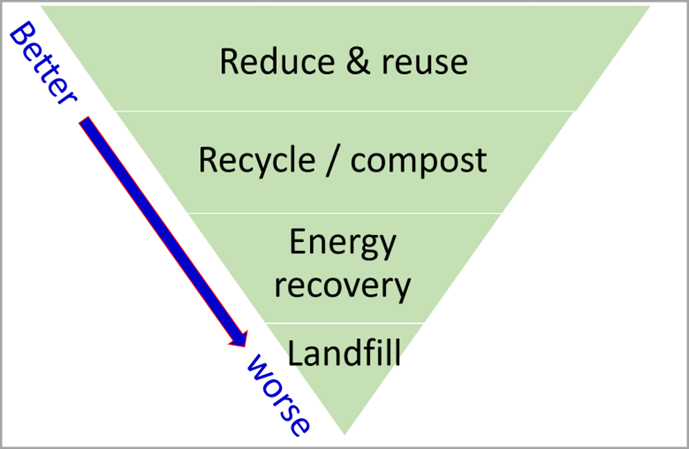

Turn this triangle upside down

The EPA suggests there should be a hierarchy for solid waste management with reduction and re-use being at the top. [2] Its graphic is reproduced below. But the problem is that our behaviours do not follow the hierarchy at all. Most of our solid waste hits the landfill, and very little is recycled or composted (only about 25% as we showed above). We need to change our behaviours to turn this triangle upside down, and that – as we have seen – requires that we overcome many challenges.

The EPA suggests that the best environmental solution is reducing and re-using solid waste, and that the worst option is for such material is the landfill.[40]

As challenging as solid waste management may be, reducing and re-using is difficult to argue with, even if there could be economic ramifications and water-use concerns (with cleaning prior to re-use). How many times have you opened a package and wondered why there is so much packaging? A package of razor blade and sunscreen are depicted below. The razor blades are very difficult to even access because of the heavy packaging. Every time I struggle with the puzzle of getting to the razor blades, I ask: “Why?” Yes, razor blades are sharp, but the packaging is ridiculous.

How about packaged materials such as sunscreens that are also placed inside cardboard boxes? It is double packaged in a bottle, then a box. This is likely done for ease of transportation, but perhaps some innovation could improve the double-packaging problem.

Products with excessive packaging – getting razor blades out of this packaging would have been a good test for Houdini.

So, what should I do about this coffee cup?

It is possible to recycle a coffee cup, though far from easy. To do so requires that the small plastic elements of the cup be separated from the cardboard elements.[41]The economics of this endeavour are arguable. [42]Given that Canadians drink an estimated 14 billion cups of coffee per year, 30% of them on the go, the best solution for the coffee cup is to never throw it away.[43]Consider the EPA’s waste management hierarchy, and take your own re-useable cup to the meeting.

If you cannot take a reusable cup, make sure you finish the entire drink, lick the lid clean, and throw the paper cup away with the other paper recyclables.

And hope – because for recycling to be effective, we need a consistent regulatory and economic system that people can understand and adhere to. We need to know into which bins we should discard things, and we need to know that the items will actually be recycled.

On a personal level, we should all seek to minimize consumption and use our purchasing power to support businesses that minimize or eliminate packaging.

References

[1] Marsh, Jane, March 24, 2021, How Much Recycling Actually Gets Recycled?, Environment

[2] United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling

[3] United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling

[4] Worldometer, United States Population

[5] United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling

[6] United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling

[7] Government of Canada, 2019, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada

[8] United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling

[9] Marsh, Jane, March 24, 2021, How Much Recycling Actually Gets Recycled?, Environment

[10] Government of Canada, 2019, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada

[11] Government of Canada, 2019, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada

[12] Simpson, Natasha, July 17, 2019, The blue bin charade: what really happens to Canadian recycling, Martlet

[13] McCormick, Etin, et al, June 17, 2019, Where does your plastic go? Global investigation reveals America’s dirty secret, The Guardian

[14] Thompson, April, July 3, 2020, A Guide to Recycling in Canada (Because Spoiler Alert: We’re Not That Good at it), Environment 911

[15] Fawcett-Atkinson, Marc, March 9, 2021, Canada is drowning in plastic waste—and recycling won’t save us, National Observer

[16] Government of Canada, 2019, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada

[17] Caulfield, Claire, January 13, 2020, What’s Up With Hawaii’s Garbage Dumps?, Honolulu Civil Beat

[18] Simpson, Natasha, July 17, 2019, The blue bin charade: what really happens to Canadian recycling, Martlet

[19] McCormick, Etin, et al, June 17, 2019, Where does your plastic go? Global investigation reveals America’s dirty secret, The Guardian

[20] Thompson, April, July 3, 2020, A Guide to Recycling in Canada (Because Spoiler Alert: We’re Not That Good at it), Environment 911

[21] Fawcett-Atkinson, Marc, March 9, 2021, Canada is drowning in plastic waste—and recycling won’t save us, National Observer

[22] Marsh, Jane, March 24, 2021, How Much Recycling Actually Gets Recycled?, Environment

[23] Simpson, Natasha, July 17, 2019, The blue bin charade: what really happens to Canadian recycling, Martlet

[24] McCormick, Etin, et al, June 17, 2019, Where does your plastic go? Global investigation reveals America’s dirty secret, The Guardian

[25] Thompson, April, July 3, 2020, A Guide to Recycling in Canada (Because Spoiler Alert: We’re Not That Good at it), Environment 911

[26] Marsh, Jane, March 24, 2021, How Much Recycling Actually Gets Recycled?, Environment

[27] Simpson, Natasha, July 17, 2019, The blue bin charade: what really happens to Canadian recycling, Martlet

[28] McCormick, Etin, et al, June 17, 2019, Where does your plastic go? Global investigation reveals America’s dirty secret, The Guardian

[29] Thompson, April, July 3, 2020, A Guide to Recycling in Canada (Because Spoiler Alert: We’re Not That Good at it), Environment 911

[30] Marsh, Jane, March 24, 2021, How Much Recycling Actually Gets Recycled?, Environment

[31] Marsh, Jane, March 24, 2021, How Much Recycling Actually Gets Recycled?, Environment

[32] Thompson, April, July 3, 2020, A Guide to Recycling in Canada (Because Spoiler Alert: We’re Not That Good at it), Environment 911

[33] McCormick, Etin, et al, June 17, 2019, Where does your plastic go? Global investigation reveals America’s dirty secret, The Guardian

[34] Fawcett-Atkinson, Marc, March 9, 2021, Canada is drowning in plastic waste—and recycling won’t save us, National Observer

[35] Fawcett-Atkinson, Marc, March 9, 2021, Canada is drowning in plastic waste—and recycling won’t save us, National Observer

[36] Fawcett-Atkinson, Marc, March 9, 2021, Canada is drowning in plastic waste—and recycling won’t save us, National Observer

[37] Government of Canada, 2019, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada

[38] Government of Canada, 2019, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste, Environment and Climate Change Canada

[39] Fawcett-Atkinson, Marc, March 9, 2021, Canada is drowning in plastic waste—and recycling won’t save us, National Observer

[40] United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling

[41] Shakeri, Sima Sept 1, 2019, HuffPost, Why can’t Coffee Cups Be Recycled? These Photos Show the Real Reason

[42] Peters, Adele, Nov 26, 2018, Starbucks recycled 25 million old paper cups into new cups, Fast Company

[43] University of Manitoba, October 12, 2018, Let’s Talk Waste: Disposable Cups, UM Today News

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2022)

Good article in the Atlantic this month on this topic. Slightly different data and analysis and but similar conclusions. The City of Calgary is on record as stating that coffee cups should be recycled but the plastic lids (with the recycling symbol on them) should go in the landfill waste. The problem is that nothing gets rinsed after use at Starbucks and I can’t imagine an unrinsed cup would make good recycling material. I would love to see a mass flow diagram from the city to see how much double trucking is done from the recycling plant to the landfill.

Thanks Shawn. I’d like to see that data, too. It is very difficult to know what the true recycling rate is. And yeah, there is not enough conversation around cleaning the plastic. Which has been on my mind too. I appreciate you sharing your thoughts.

Thanks George. Great comments as always. We have spoken about this on other platforms, but it is worth saying again here that we could stand finding more clever solution to “theft” than a magician-proof level of packaging. I appreciate you pointing this out.

Good article Lee; from what I have been able to gather the best thing we can with waste plastics is to incinerate them to create electricity. Modern incineration can be quite clean and efficient especially if combined with some kind of carbon capture technology. I have no idea if carbon capture can function in this kind of situation.

A great deal of excess packing as shown above with the razor blades is to reduce theft. Theft has a massive cost to the consumer directly and indirectly a significant cost to the environment.

Most glass that is rejected is due to being dirty, redesigning glass containers to be easier to clean and labels that come off with less effort and water would help. A good percentage of glass that is recycled goes into fibreglass insulation and if I recall correctly that industry would gladly take more from the recycling system is more clean glass was available.