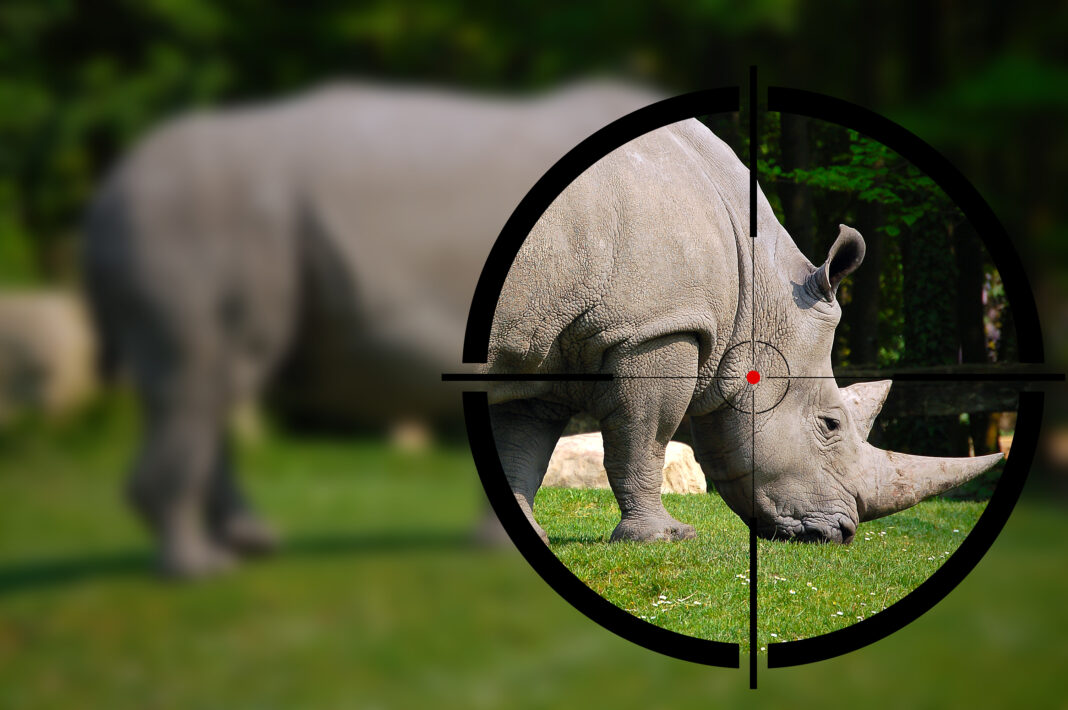

Big-game hunting elicits high emotions around the world, but it plays an important role in the conservation of nature and wildlife in Africa, as well as in local economies. Before taking a public stand or making rash policy decisions, it is worth considering the facts.

Trophy hunting is the highly visible and highly controversial apex of a complex wildlife, tourism and conservation industry in countries including South Africa.

It is an easy target for animal-rights activists, and groups such as the Humane Society and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals exploit its controversy with much success.

Among their biggest achievements has been to convince at least 45 international airlines[1] to refuse to ship hunting trophies on behalf of customers, according to Humane Society International.

American big-game hunters who travel to South Africa and post images of their hunts on social media are frequently eviscerated online. These hunters are often women, including Olympic skeet shooter Corey Cogdel,[2] Texas cheerleader Kendall Jones,[3] and television presenter Melissa Bachman.[4] In each case, the online vitriol extended to crude sexism and threats of harm to the hunters and their families. Following Bachman’s post that included a photo of herself kneeling with a rifle over a fallen lion and text concluding with “… what a hunt!”, actor/comedian Ricky Gervais, well known for his animal-rights advocacy, famously tweeted “spot the typo”.

Perhaps the most infamous case was that of Minnesota dentist Walter Palmer,[5] who shot a big-maned lion known as Cecil in Zimbabwe in 2015. Initially, it was alleged that the hunt was illegal, but the case went to court and the hunt was ruled to be legal.[6]

To urban elites, hunting is likely to offend the sensibilities. Anti-hunting activists make the case that hunting demonstrates a disrespect for nature, or poses a threat to the survival of game species. Such appeals to emotion, however, fail to engage with the underlying facts of how the practice of hunting intersects with local communities, wildlife ranching, and conservation.

There exist two main models of conservation. The first is familiar to Americans and Canadians, and originated with president Teddy Roosevelt. The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation[7] is based on the concept that wildlife is a public resource, is owned by no one, and is held in trust by government for the benefit of present and future generations.

It also holds that markets for wildlife and wildlife products are, with few exceptions, unacceptable because they privatise a common resource and pose a threat to game populations. Under this model, hunting is regulated in great detail by the state through permits, hunting seasons, and quotas. Wildlife may only be hunted for a “legitimate purpose”.

Hunting for the pot is not a legitimate purpose. Neither is hunting for the thrill of the kill, nor hunting for profit. The only form of hunting that the North American Model deems acceptable is sport hunting, in which the hunter does so primarily for the pursuit or chase, affords game a “sporting” chance, inflicts no unnecessary pain or suffering on game, seeks knowledge of nature and the habits of animals, derives no financial profit from game killed, and – curiously, given that one may not hunt for sustenance or profit – will not waste any game that is killed.

Finally, it was Roosevelt’s view that everyone ought to have access to wildlife hunting, regardless of their wealth, social position, or land ownership.

The North American Model has been described as flawed and inadequate[8] by a group of scientists led by Michael P. Nelson, associate professor of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy in the Lyman Briggs College, the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, and the Department of Philosophy at Michigan State University. Some wildlife continued to decline, while populations of others such as white-tailed deer and coyotes exploded to the point of becoming pests. Because everyone has an inherent right to enjoy nature, overcrowding in American National Parks is causing untold damage to wildlife and the environment.

The failure of this model gave rise to an entirely new, parallel field of study; conservation biology, which describes itself as a “crisis discipline”. This field views all recreational hunting as a minority interest that no longer plays any role in conservation.

Believing that wildlife is common property leads conservation biologists to value the opinions of people who may have no knowledge of, or interest in, the conservation of nature or the protection of wildlife.

The second model of conservation involves establishing private property rights in wildlife. This is the model that has been adopted by some African countries, including South Africa. It has led to remarkable conservation success stories.

During the colonial era, big-game hunters had little regard for conservation. Game was not owned by anyone – the legal term for which is res nullius – and there was no conservation management at all. Vast herds of big game on the African plains were destroyed in the 19th century.

Early in the 20th century, national parks were established to conserve game and wild ecosystems. Although they halted over-exploitation by hunters, they had limited success at re-establishing species that had been hunted almost to extinction.

Starting with white rhino in the 1950s, breeding stock of species that had been hunted to the brink of extinction was exported from the national parks to selected private game reserves, private game ranches, and private zoos.

Most of the animals acquired by private game farms were promptly hunted. The South African Parks Board despaired of private game ranches ever contributing to the breeding and conservation of animals such as rhinos.

There were two reasons for this. In 1982, a trophy hunt would bring in six times the list price for a white rhino. Nobody in their right mind would bother breeding rhinos if they could make a quick 600% profit by simply acquiring the animal from the Parks Board, and nobody did. The Parks Board doubled, then tripled the list price, but with little effect.

In 1985, however, private game owners put the first rhinos on auction. Market prices soared and, by 1989, a rhino was worth 50 times what it was worth in 1982. By 1990, the list price system was abandoned in favour of auctions, and the margin on a trophy hunt had declined from 600% to 60%.

On its own, this wasn’t enough to change the dynamic. Before 1991, all wildlife in South Africa was treated by law as res nullius. In that year, though, a new law established private ownership of any game animals that could be legally identified by means such as a brand or ear tag.

The combination of secure private property rights and market pricing were all the incentives private game ranchers needed. It now made financial sense to breed rhinos, and hunt them selectively.

White rhino numbers grew strongly, from fewer than 6,000 in 1991 to 21,000 in recent years. Despite a poaching crisis that arose at the same time, legal trade in rhino horn was banned, and the white rhino is no longer considered endangered or threatened. Environmental economist Michael t’Sas-Rolfes describes[9] the saving of the white rhino as “a market success story.”

The same happened with other animals. South Africa’s national parks, where hunting is prohibited, are home to 3,000 lions, and are at carrying capacity. A further 8,000 lions exist on game farms, where they earn their keep through ecotourism and hunting.

A team of conservation biologists led by Peter Lindsey evaluated the role of trophy hunting in conservation,[10] and concluded that the annual off-take of between 2% and 5% of male lions to be ”sustainable and low risk if well managed.”

South Africa’s model is a hybrid of publicly owned game protected in national wildlife parks where hunting is not permitted, and privately owned game hosted on wildlife ranches that specialize in breeding, ecotourism, meat production, or hunting.

National parks account for 5% of the country’s land surface area. Private wildlife ranches account for 17%. The number of head of game is similarly distributed. Thanks, it seems, in large part to private wildlife ranching, there are now more game animals in South Africa than at any time in the recorded past.

The conservation is funded in various ways.

According to a 2016 study[11] by the Endangered Wildlife Trust, game meat produces revenue of USD $2.43-$2.75 per hectare, biltong (dried meat) hunting delivers $5.31 a hectare, live sales produce $13.24 a hectare, and trophy hunting yields $15.34 a hectare. About half of live sales revenue is dependent on the hunting industry.

Wildlife ranches often exist on land that is marginal for agriculture, and most ranches are located off the beaten tourist track. According to Wouter van Hoven[12] of the Centre for Wildlife Management at the University of Pretoria, ecotourism accounts for only 5% of the industry’s revenue. Meat production earns 7% of total revenue, live sales make up 16%, foreign hunters account for 18%, and local hunters account for 54% of the industry’s total revenue.

In total, about 80% of South Africa’s wildlife ranches conduct consumptive use activities, hunting accounts for 72% of total revenue, and ecotourism accounts for 5%. Remove hunting from the equation and, it could be argued, most private wildlife ranches would become economically unsustainable.

This has many consequences. Not being able to sustain the losses, most owners would likely be forced to revert to cattle ranching or crop farming, which means the wild land would be lost to conservation.

This would have negative effects not only for big-game conservation, but would lead to land degradation and pose a threat to smaller animals and plants that are part of these ecosystems.

Local communities that do not see economic value in game animals are liable to turn to poaching. Livestock farms employ fewer people per unit area than wildlife ranches, which means communities would face higher unemployment and greater poverty if the ranches went under.

According to a paper[13] by the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s Andrew Taylor and others, the financial and social benefits of wildlife ranching on marginal land make this a viable land use, and the South African model could be a suitable option for other African countries seeking sustainable land-use alternatives.

Writing about the impetus for a ban on trophy hunting in the aftermath of the Cecil the Lion incident, Rosie Cooney, chair of the IUCN’s CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group of the Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy and Species Survival Commission at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, claimed that such bans would not contribute to conservation, and local communities would pay a heavy price.

She points out that bans on trophy hunting in Tanzania (1973-78), Kenya (1977) and Zambia (2000-03) accelerated the loss of wildlife due to the removal of incentives for conservation.

There is complex interaction between poor local communities seeking sustenance and jobs, economic actors that make land-use choices, and the highly successful model of wildlife conservation pioneered by South Africa. This is almost entirely absent from the popular narrative about big-game hunting.

While emotions may run high against trophy hunters, the numbers indicate that they play a critical role in financing conservation on the African continent.

By Ivo Vegter

[1] https://www.hsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Airlines-prohibiting-hunting-trophies-Jan-2020.pdf

[2] https://www.petersenshunting.com/editorial/anti-hunters-slam-olympic-shooter-corey-cogdell/273095

[3] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2675807/Animal-lover-outrage-blonde-Texas-cheerleader-smiles-dozens-photos-alongside-rare-big-game-hunts-African-safaris.html

[4] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2013-11-19-in-defence-of-a-lion-killer/

[5] https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2015-08-03-cecil-the-lion-lessons-in-misplaced-outrage/

[6] https://www.yahoo.com/news/zimbabwe-court-drops-charges-against-hunter-helped-kill-110032896.html

[7] https://www.fws.gov/hunting/north-american-model-of-wildlife-conservation.html

[8] https://www.isleroyalewolf.org/sites/default/files/Nelson%20et%20al%202011-An%20Inadequate%20Construct.pdf

[9] https://www.perc.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Saving-African-Rhinos-final.pdf

[10] https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00594.x

[11]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293958705_An_assessment_of_the_economic_social_and_conservation_value_of_the_wildlife_ranching_industry_and_its_potential_to_support_the_green_economy_in_South_Africa

[12] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-017-9529-6_6

[13] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320719315137

(Ivo Vegter – BIG Media Ltd., 2021)