A team of space scientists affiliated with multiple institutions in the U.S., working with a colleague from Italy and another from France has used modeling to partially explain the resilience of cyclones circling Jupiter’s poles. In their paper published in the journal Nature Astronomy, the group describes how they analyzed images captured by the Juno space probe and used what they learned to create shallow water models that might at least partly explain how the cyclones last so long.

In 2016, NASA’s Juno space probe entered an orbit around Jupiter. Unlike other such probes, it has been circling the planet from pole to pole, rather than around its equator, Phys.org reports. As the probe began sending back pictures of the planet from this new perspective, researchers looking at them found a surprise. Not only was there a single cyclone sitting atop each of the poles, but both were surrounded by more cyclones. As time has passed, more pictures of the poles have arrived and the researchers studying them continue to be surprised by the stability of the cyclones — the original ones are still there today and have not even changed shape. Such behaviour is of course unheard of here on Earth — cyclones take shape, travel around for a while and then dissipate. The Jupiter storms have left researchers scrambling to come up with a reasonable explanation for what they have observed.

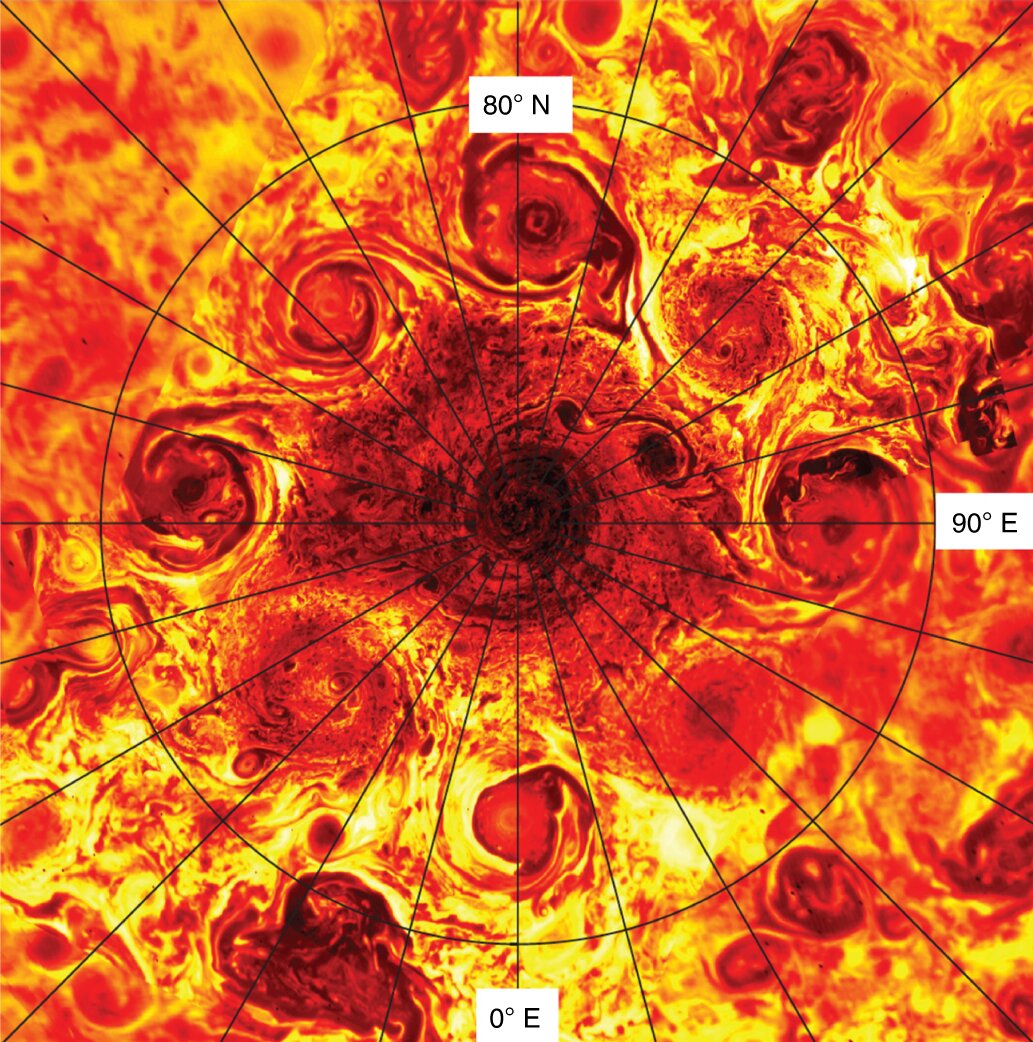

Photos of the planet’s north pole show that there are eight cyclones surrounding the central cyclone directly over the pole. All eight are in close proximity and are nearly equidistant from the central cyclone — and are arranged in an octagonal pattern. At this time, it is not clear if the cyclones rotate around the centre. There is a similar arrangement at the southern pole, only there are just five cyclones, shaped as a pentagon. In this new effort, the researchers have tried a new approach to explaining how it is that the cyclones hold in place for so long, and how they do it without changing their position or shape.

The work by the team involved analyzing pictures and other data from the Juno probe, looking specifically at wind speeds and direction. They then took what they learned and used it to create shallow water models and that led them to suggest that there is an “anticyclonic ring” of winds that move in the opposite direction of the cyclones, which is what keeps them in place. And while that may hold true, the team was unable to find signatures of convection, which would have helped to explain how heat was being used to fuel the cyclones. They acknowledge that much more work will need to be done to fully explain the behaviour of Jupiter’s cyclones.

https://phys.org/news/2022-09-cyclones-circling-jupiter-poles-baffling.html