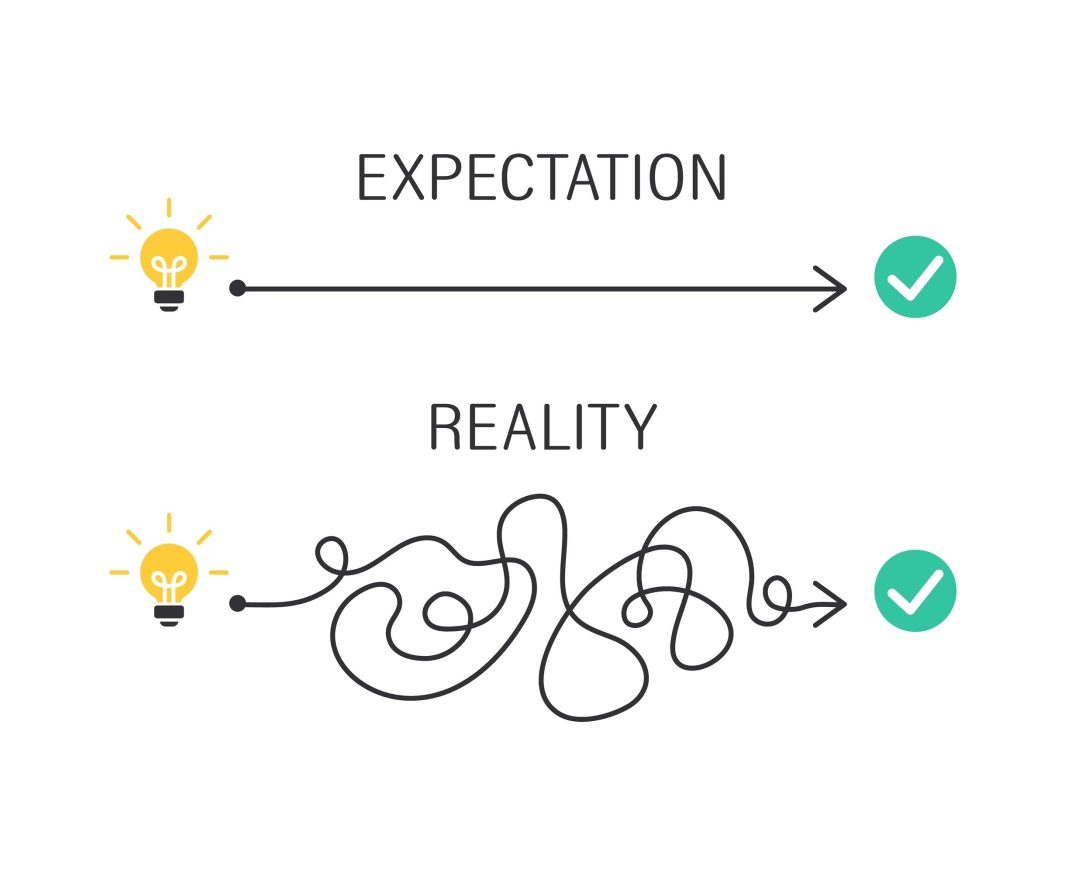

Some people are convinced we live in a time of unprecedented and existential crises. Many of their feelings are magnified in today’s social and mainstream media, where activists urge political leaders and society to take drastic and immediate action to address the perceived problems.

To them, we (society/government) know what to do, so we just have to “get on with it”. And often, if we don’t just get on with it, they accuse industry and government of greed and corruption.

Sample exhortations from LinkedIn posts on that most critical crisis of all, changing climate:

“This is the road we are on. No time to wait.”

“Time to protect the sacred. We have the solutions. Implement them.”

“How long will our leaders fail to do what is required to avert disaster?”

“We have so many solutions. Implement them.”

Indeed, we have lots of technologies and strategies to address greenhouse gas emissions – so why don’t we just “get on with it” and solve the problem?

Because real life is not that simple. Let’s examine a few strategies around reducing emissions in the real world – where we need to plan, finance, and execute actual physical projects to create the desired results.

Example #1 – Carbon capture and storage (CCS)

Carbon capture and storage is regarded by serious analysts as a key and necessary component of the effort to reduce humanity’s GHG emissions, as I discussed recently (Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) – effective technology or convenient scam?). Even alternative energy proponents such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) see CCS as a critical component of emissions control (Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage ).

The enabling technologies for CCS – capture, transportation, and geological storage – are all well-established, and successful projects date back to the 1990s. So we should be full speed ahead on new CCS projects, right?

Not so fast.

Pathways Alliance, a consortium of oilsands producers in northern Alberta, have proposed

“a carbon capture and storage network and pipeline that when operational will have the capacity to transport captured CO₂ from multiple oil sands facilities to a hub in the Cold Lake area of Alberta for permanent underground storage.” (Pathways Alliance)

The volumes of CO2 to be stored instead of being released to the atmosphere are several megatonnes per year, enough to significantly reduce Canada’s annual GHG emissions. Pathways knows how to build the capture facilities, how to pipeline the CO2 to the storage site, and where to inject it into permanent safe storage. But the project is challenged by:

-

- Negotiations with the federal government regarding commercial arrangements, so that Pathways can justify the huge amounts of money they are being asked to invest

- The engineering, geoscience, and project management work that must be done to ensure the project proceeds safely and efficiently

- Interventions by obstructionist anti-oil groups such as Ecojustice (“we help people like you take governments and polluters to court”) pushing for extra studies and environmental reviews – Alberta’s energy regulator will not require environmental impact assessment of Pathways Alliance project

As a professional geoscientist supporting applications for other carbon storage project proponents, I can attest to the very rigorous process Pathways must face to meet the environmental standards imposed by the Alberta Energy Regulator. Ecojustice is simply pushing for delay. Additional reviews would accomplish nothing to benefit the environment or to local communities, but would add time and more costs.

Once built, CCS projects will reduce net emissions from many industries, including power generation, refining and petrochemicals, cement production, and biofuels synthesis. But while we understand how to do it, there is a lot of work necessary in order to do it right in different places.

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) is backing research over seven years to advance the commercial viability of CCUS, and once this work is complete in 2028, we will have more knowledge to build on CCS potential across Canada and will be in position to share critical information and best practices with industry in other regions.

Example #2 – Energy storage

If we are going to increase the proportion of intermittent renewable power generation in electricity supply, we need to be able to store energy more cheaply and efficiently.

While batteries are best known for energy storage, they are expensive and impractical for large grid-scale applications. Pumped hydro is the current global leader, but we need more choices. Storing energy in underground caverns is a viable alternative – either by compressing air (Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES)) or by storing hydrogen manufactured by wind or solar electricity.

Again, we are talking about a well-known technology that has been used for decades, primarily to store natural gas for seasonal use (The Basics of Underground Natural Gas Storage). It should be simple to just build a bunch more caverns to store hydrogen or compressed air, right?

Maybe not.

Geological Survey of Canada researchers recently published a paper in the Bulletin of Canadian Energy Geoscience (CEGA Bulletin – available only to subscribers) examining the potential for hydrogen storage in salt formations of Western Canada. They found significant risks arising from chemical reactions between salt impurities and highly reactive hydrogen that could threaten the integrity of hydrogen storage – risks that do not exist for less-reactive natural gas storage. This issue must be addressed before large-scale hydrogen storage – assuming that ever happens – can be created.

While the reactivity problem likely does not apply for compressed-air energy storage (CAES), there may still be issues arising from CAES pressures and frequency of injection/production that challenge conventional salt cavern applications.

Example #3 – Supply chains

Robust and reliable supply chains, particularly for critical minerals to build new energy tech such as solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries, are an absolute must for energy transition and emissions reduction Critical minerals to play major role in emerging technologies. Yet China has secured market control for many critical mineral commodities, threatening to restrict their access – China’s dominance over critical minerals poses an unacceptable risk. Political and industry leaders are urging more investment in the West to reduce supply chain risk and to ensure we can build all the energy tech we need – China’s critical minerals dominance ‘material risk’ to national security, Teck Resources CEO warns.

Great idea – so how quickly can we fill out those supply chains? Don’t hold your breath – and here is one reason why.

Lithium is one of those key critical materials, and entrepreneurs have been working hard to develop an entirely new source outside of the existing hard-rock mines and remote salars of the High Andes. They propose to produce lithium from highly saline brines found in sedimentary basins around the world, using oilfield data and technologies plus innovative chemical extraction techniques. Industry leaders Standard Lithium in Arkansas (Standard Lithium ) and E3 Lithium in Alberta (E3 Lithium ) have done years of groundwork to set the stage, and have secured industry partners with deep pockets to pilot commercial extraction.

These companies are staffed with great people who have done brilliant work over the past decade – but they haven’t yet crossed the commercial finish line. Optimizing direct lithium extraction (DLE) is the biggest hurdle to commerciality – being able to process tens of thousands of cubic metres of corrosive salt water every day, and to extract all the lithium at concentrations as low as 75 parts per million (ppm). E3’s website says:

“The company ultimately decided on a third-party technology that was highly prepared for commercialization. The goal is to get to commercial operations and revenue generation as quickly as possible.”

Until Standard, E3, and others cross the commerciality finish line, lithium will continue to be a critical material with uncertain supply chains that will slow the development of new energy tech to reduce emissions.

So … can we just ‘get on with it’?

Reducing GHG emissions requires development and commercialization of many new (and existing) technologies at scale – and each faces its own challenges.

Yes, we can safely store a lot of unavoidable CO2 from industrial operations – but it takes time to work out the finances, to design the specific projects, and to deal with anti-industry advocates.

Certainly, we can store compressed-air energy and hydrogen in underground salt caverns, but we have a lot of work to ensure that they are safe, efficient, and secure.

No doubt, innovators will dramatically improve the critical mineral supply chains upon which the energy transition must be built – but how much time do they need to successfully and commercially innovate?

Perhaps most importantly, humanity faces many challenges – energy security, poverty, famine, war, and others. How much time, money, and effort is really available for us to “just get on with” addressing emissions and climate change when most global citizens have many higher priorities?

I suggest we take a broader view of humanity and its issues when challenged by single-issue advocates who insist we can solve their particular problems if we just drop everything else and try harder.

(Brad Hayes – BIG Media Ltd., 2024)