Students’ identities can play a key role in how comfortable they feel and how often they speak up in the classroom, especially in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

For instance, women generally speak far less than men in undergraduate engineering classes. But this is not always the case, according to Princeton researchers. When classes are taught by women instructors, the gender gap practically disappears.

Another major factor in women’s class participation is participation by other women – the researchers found that women are much more likely to speak after another woman has spoken in class.

“That was one of the findings that I was most excited about, because it felt like something that could really be leveraged to change teaching practices,” said study co-author Nikita Dutta, who completed a PhD in mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton in 2021, and is now a director’s postdoctoral fellow at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. “It’s kind of like a waterfall effect once one woman starts to participate.”

While much progress has been made in recent decades, women remain significantly underrepresented in engineering and other STEM fields. In 2018, women earned 22.2% of engineering bachelor’s degrees in the United States. (Princeton Engineering’s current undergraduate population is 41% women.) Previous work has shown that experiences with mentors, peer groups, and classroom climates play critical roles in undergraduate women’s success in engineering.

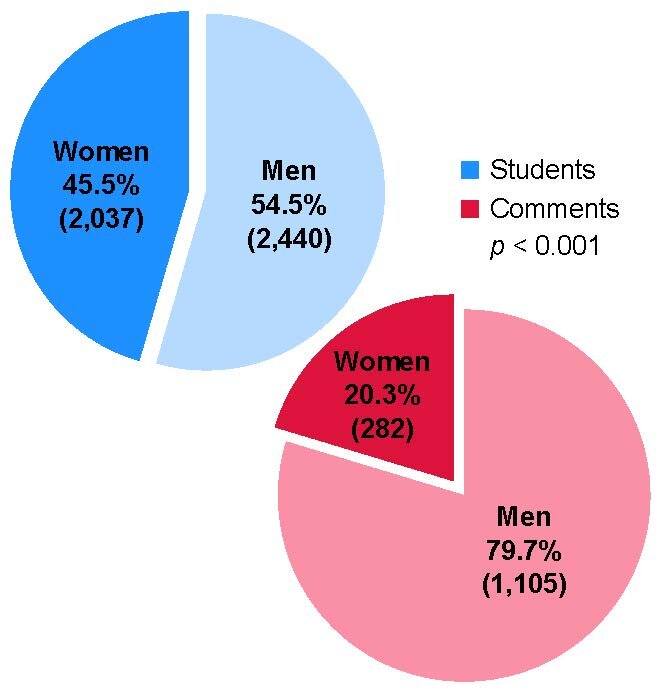

The study, published online in IEEE Transactions on Education, included observations of 1,387 student comments over 89 class periods in 10 courses in Princeton’s engineering school. Five of the courses were taught by women, and five were taught by men, although only 30 of the observed class periods were taught by women. While the students observed in the courses were 45.5% women and 54.5% men, only 20.3% of the classroom comments came from women. (The study setup did not allow for students to self-identify their gender; the observers noted the perceived gender of each student as “man,” “woman” or “non-binary”.)

This gender gap widened slightly when the researchers considered only courses taught by men (17.1% of comments came from women in classes taught by men versus 20.3% overall), but almost disappeared with a woman instructor. In classes taught by women, comments from women students increased to 47.3%.

Investigating the timing of students’ comments, the researchers found that after one woman participated in class, during the next minute the proportion of comments by women rose to 32.4% – an effect that waned over time but lasted for nine minutes after the initial comment.

Dutta conducted her dissertation research with Craig Arnold, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering and director of the Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials.

During lectures, she noticed that women seemed to answer questions and offer comments less often than men. She started tracking students’ participation informally, and found variability from one class session to the next. She became curious about what might be behind these fluctuations, and whether other engineering courses might reveal larger trends. At the semester’s end, Dutta presented her findings to Arnold and the rest of his research group during their weekly meeting.

“My jaw dropped,” said Arnold. “I thought, ‘This is remarkable, this is incredible.’ She started talking about her plans … and ultimately it turned into a real scientific study,” said Arnold, who co-authored the paper with Dutta.

Dutta and Arnold submitted a proposal to Princeton’s Institutional Review Board, which oversees research on human subjects. They also consulted with pedagogy and educational assessment experts at Princeton’s McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning, where Dutta had been trained as a graduate teaching fellow.

During the next two semesters, they enlisted other graduate students to assist with observations in lecture courses representing different class sizes and levels. Although the study was curtailed by the COVID-19 pandemic, they were able to gather sufficient data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Besides recording student commenters’ genders, observers labeled comments as “unprompted”, “solicited”, or “involuntary.” The gender gaps in unprompted and solicited participation were similar to the overall gender gap. The number of involuntary comments was small, since only three of the 10 instructors called on students who had not raised a hand, but the observations suggest that instructors called on men and women equally.

https://phys.org/news/2022-03-strategies-gender-gap-courses.html