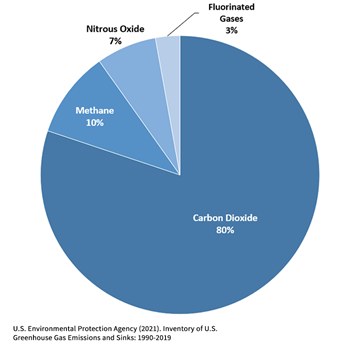

Every activity, natural or manmade, from breathing to driving, generates emissions of some kind. Certain emissions are worse than others, causing pollution or, in large quantities, affecting the composition of the atmosphere. Greenhouse gases (GHGs), in particular carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), generated by modern industry, transportation, and agriculture, have been rising steadily since the industrial revolution. These emissions are implicated in manmade influence on climate. Figure 1 shows the relative proportion of GHG emissions in the US in 2019.[1]

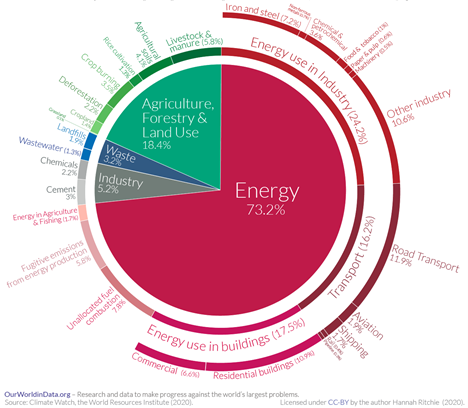

Close to three-quarters of all manmade GHG emissions come from energy use in industry, transportation, and heating/cooling of buildings (Figure 2). The next largest source of emissions is the agriculture sector, accounting for a further 18%, with the remainder produced by waste, cement, and chemicals.[2]

Figure 2: Global greenhouse gas emissions by sector, 2016.

The largest proportional component of greenhouse gases is CO2, sometimes simply referred to as “carbon”. Although carbon and carbon dioxide are not the same, they have become synonymous in political and media discussion of climate change. Carbon dioxide gas (CO2) is one of the places carbon resides, but carbon is a ubiquitous chemical in everything on earth, including living organisms. Carbon comprises 18% of our body weight and is literally part of our DNA.[3]

Just like other elements in the earth, carbon naturally cycles through the atmosphere, oceans, plants, animals, and soil in a complex interaction of chemical and physical processes. In part of that cycle, it can get sequestered for millions of years, as sediments and dead organisms sink to the bottom of oceans or lakes and are transformed by increasing pressures and temperatures into solid rock and fossil fuels. Carbon captured this way is normally gradually released back into the system through erosion and fluid maturation and migration, but humanity’s direct extraction of fossil fuels has accelerated part of this process, shortcutting the natural carbon cycle.

There is no doubt that the burning of fossil fuels is a significant source of GHGs, particularly CO2. But in addition to the gradual natural processes just mentioned, there are catastrophic (in the geological sense) natural events that release massive amounts of gases and particulate matter into the atmosphere. Look at this spectacular picture of the Taal volcano in the Philippines erupting in 2020 (Figure 3).[4]

Figure 3: Eruption of the Taal volcano in the Philippines on January 12, 2020. The gas and ash plume reaches 17 kilometres high.

One large volcanic eruption such as Taal can release millions of kilograms of GHGs into the atmosphere. Between May 3 and Aug. 5, 2018, the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii erupted. On one of those days, July 11, an estimated 77.1 kilotons (70,000 metric tonnes) of CO2 were emitted.[5] If that amount is assumed on every day of the eruption, this volcano was responsible for adding 6.57 million metric tonnes of CO2 to the atmosphere. Remember this number when we get to the calculations of human contributions.

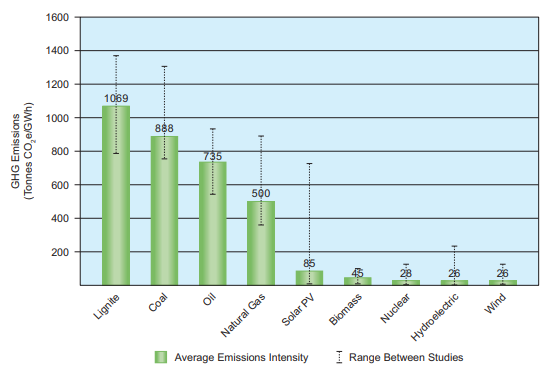

Figure 4: Lifecycle GHG emissions intensity of electricity generation methods.

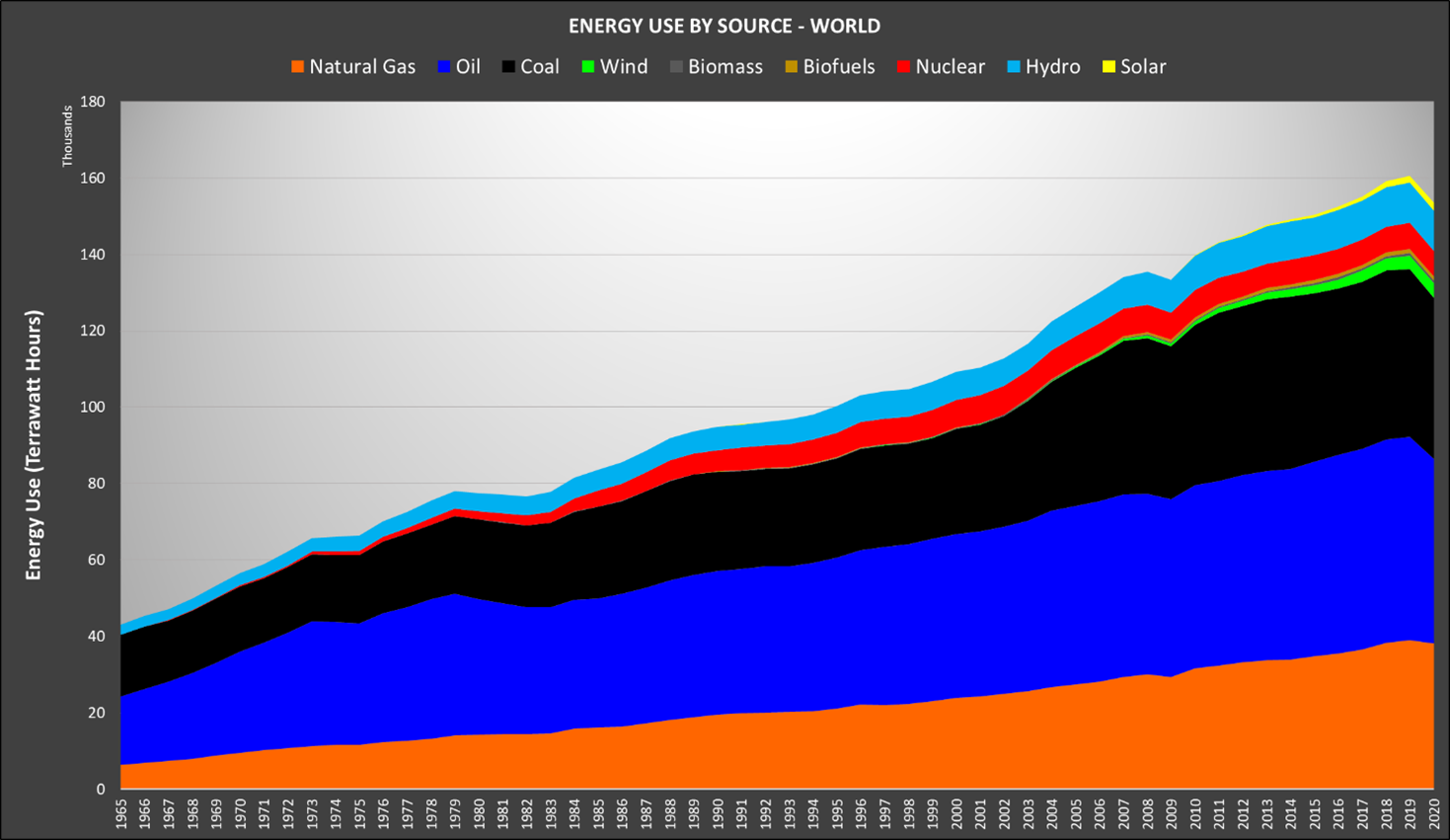

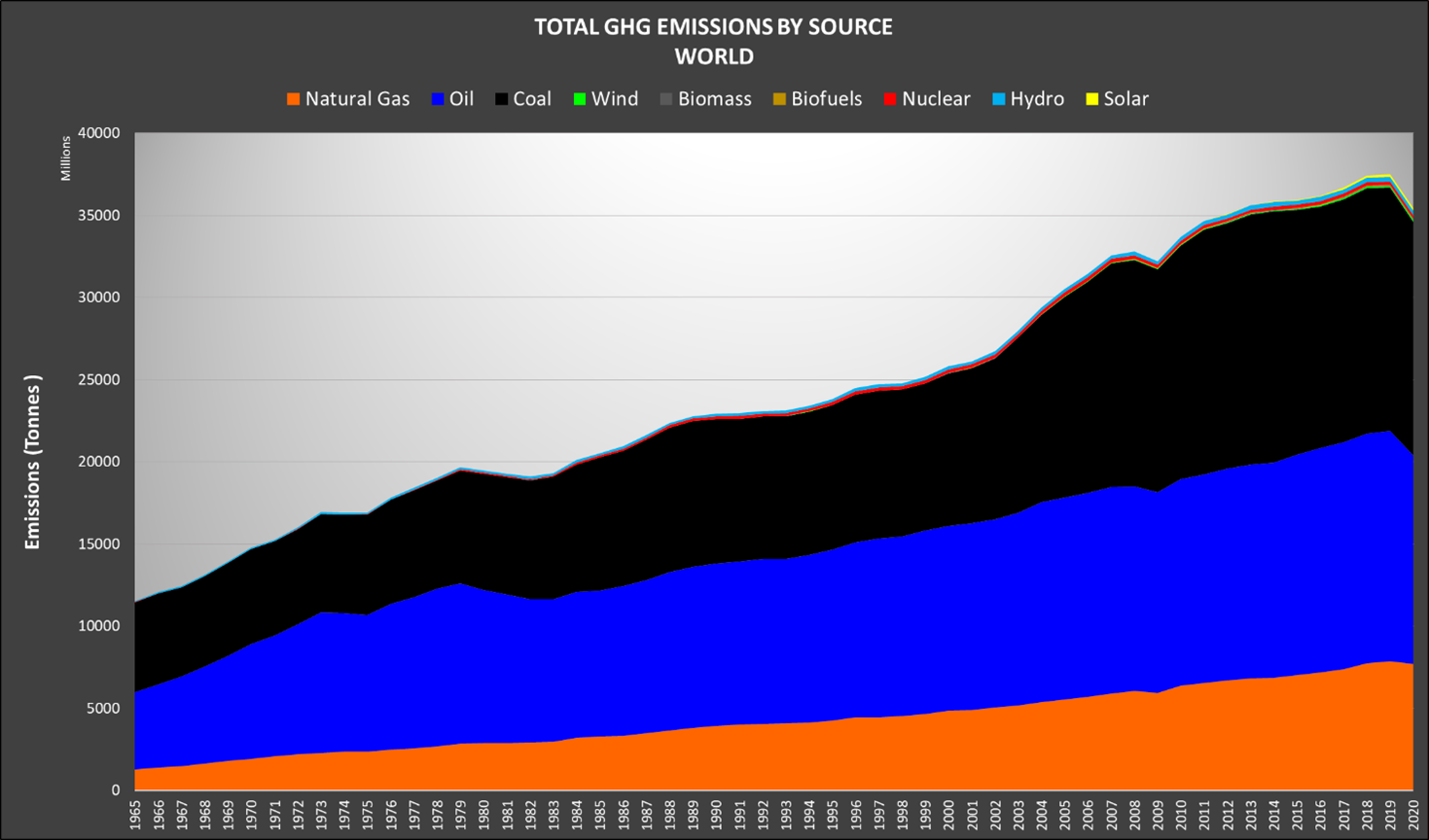

A recent BIG Media article, Climate change and energy: context for the great debate, reported global energy use by source from 1965 to 2020 (Figure 5 top).[6] Each of these sources have associated GHG emissions according to the life-cycle estimates shown in Figure 4.[7] [8] [9] Substituting the appropriate mean emissions intensity for each of the energy sources shows us the contribution of each of those energy sources to global emissions (Figure 5 bottom).

Figure 5: Top – global energy use by source, 1965-2020. Bottom – global emissions by energy source, 1965-2020.

Total emissions worldwide in 2019 were 37.5 billion tonnes. This is more than 4 million tonnes per hour. Recalling the number from the Kilauea volcanic eruption of 6.57 million tonnes, to put this in perspective, 94 days of eruption of a large volcano emits as much CO2 as about 1.5 hours of human activity.

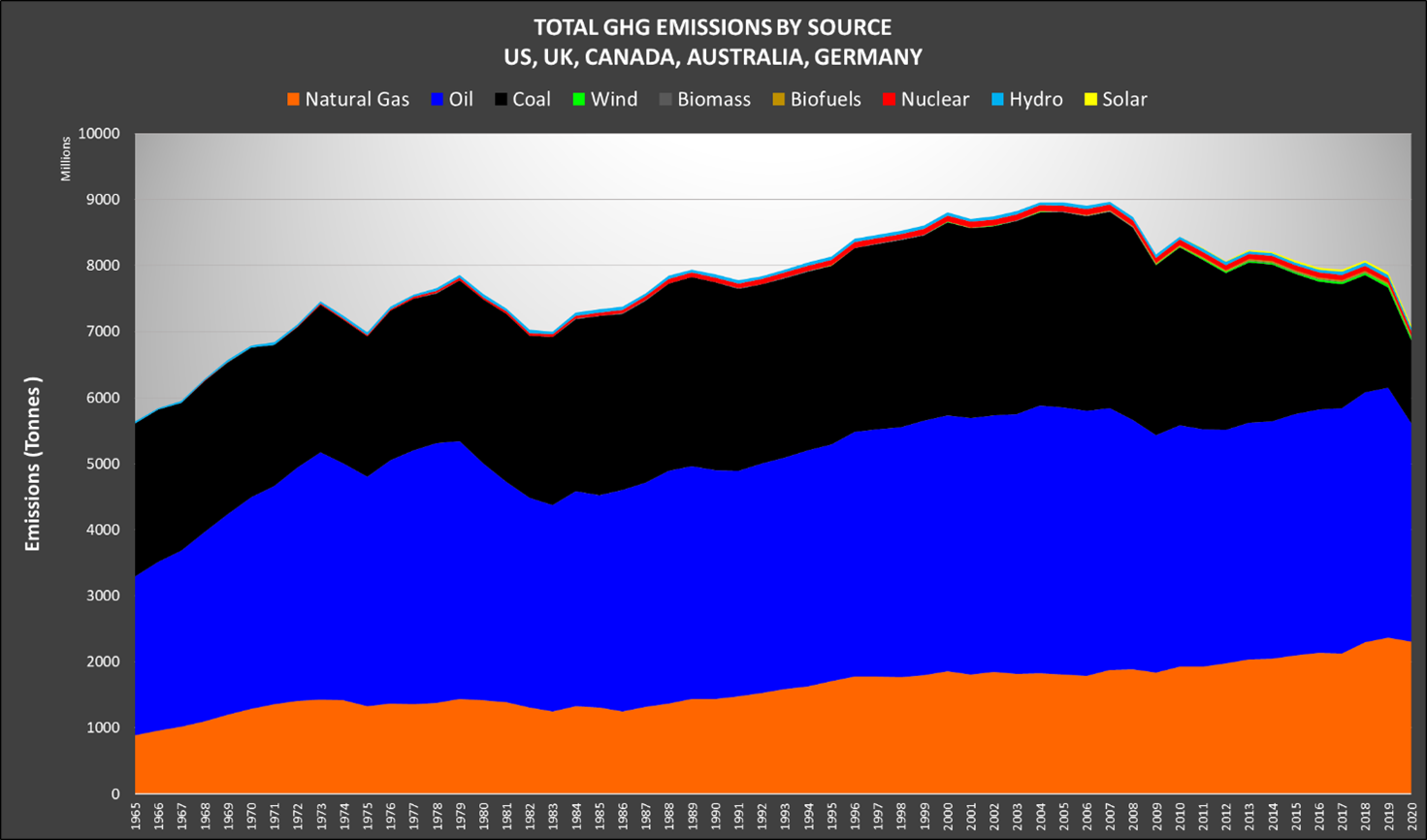

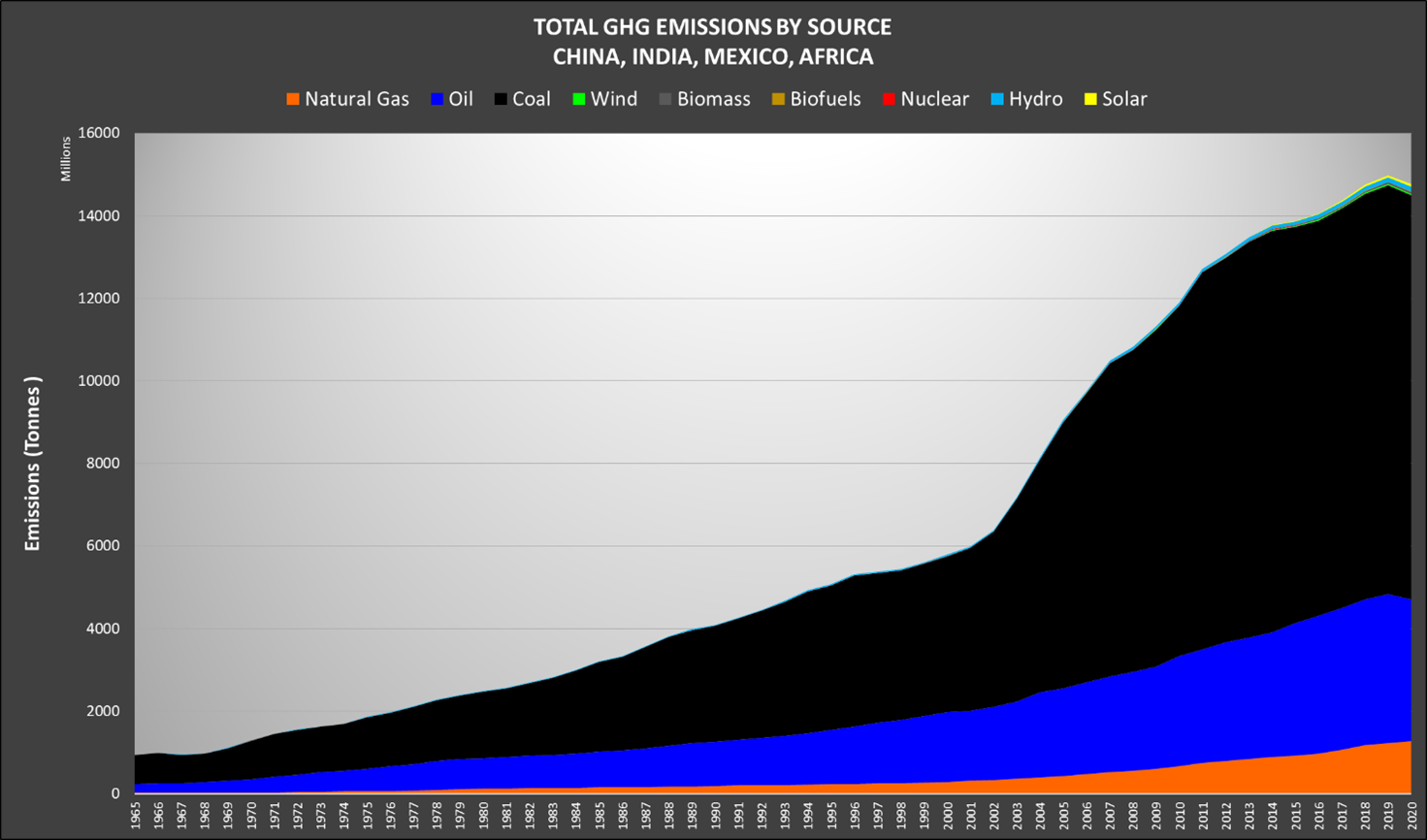

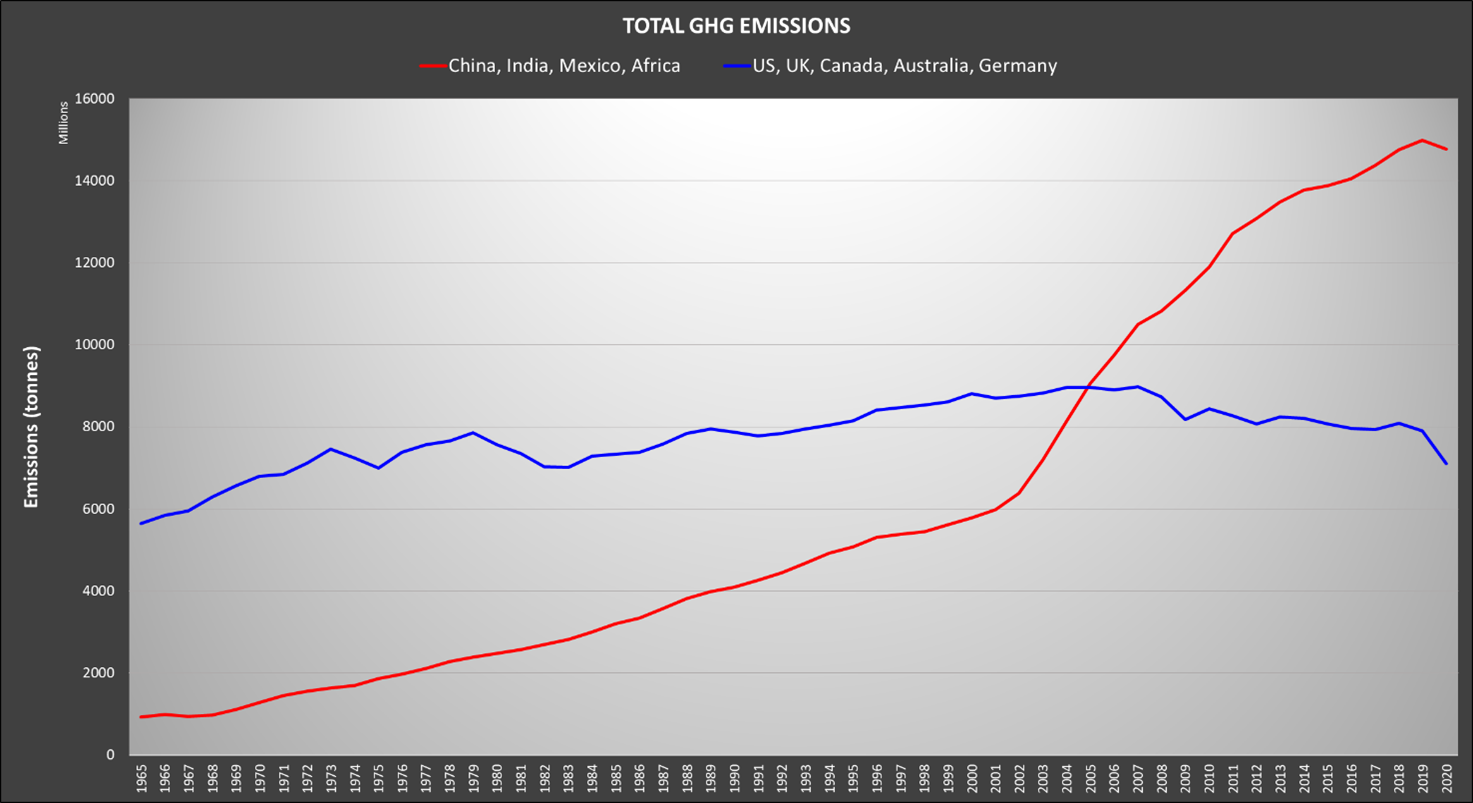

Figure 5 shows that fossil fuels are the largest emitters among the energy sources. But not all fossil fuels are created equal. Coal, for example, contributed 27% of the global energy mix in 2019, but its use was responsible for nearly 40% of emissions. Natural gas is the cleanest-burning fuel with emissions intensity approximately half that of coal for the same energy output. Replacing coal with natural gas reduces emissions. Why is that relevant? The answer can be seen in the emissions charts (Figure 6) divided between a selection of “first world” countries (U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, Germany) and a selection of developing countries (China, India, Mexico, Africa).

Figure 6: Total GHG emissions by source. Top: U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, Germany. Middle: China, India, Mexico, Africa. Bottom: Totals from each group on the same scale.

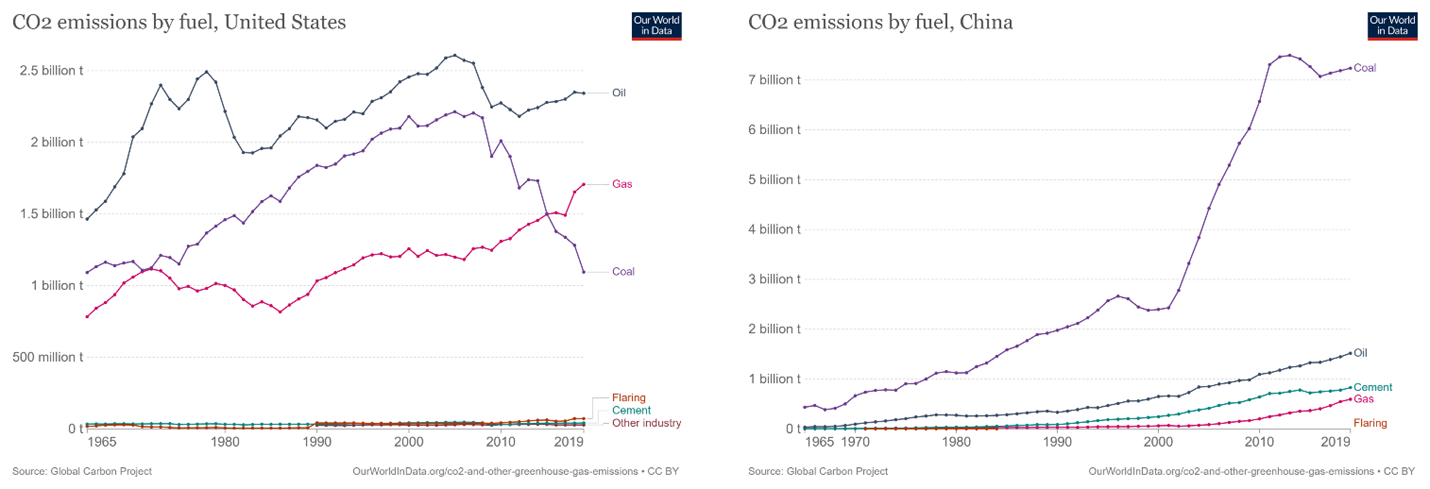

It is apparent from these charts that emissions in the developing world are growing at an alarming rate. While other sources contribute, coal dominates this profile. At the same time, emissions are decreasing in the developed countries shown, due to energy efficiency combined with the reduction in coal use. This effect is illustrated in more detail in Figure 7, comparing CO2 emissions by fuel type for the U.S. and China. In the year 2000, the U.S. and China were approximately equal in contributions from coal. Since then, the U.S. has decreased CO2 from coal by 50%, and China has increased by 300%.[10] Emissions from natural gas are rising, but, as they offset coal, this results in an overall reduction.

(The per-capita comparison tells a different aspect of this story. For more on that perspective, see the BIG Media article mentioned earlier.)

Figure 7: CO2 emissions by fuel type, US and China.

Modern society has been driven by fossil fuels, the availability of which directly powers standard of living. In recent years, gross domestic product (GDP) has become decoupled from energy use in the developed world due to an emphasis on energy efficiency and the growth of natural gas use over coal. This is not yet the case in developing countries. As they strive for the same standard of living as the first world, energy use follows (or leads). In general terms, the absence of accessible energy equates to poverty.

Efficient new technology takes decades to develop and scale up. Modern renewable technologies (solar and wind) have grown with concerted efforts over the last two decades. Despite this focused effort, their share is barely keeping pace with growth in energy demand. In 2019, solar and wind energy generation accounted for only 3.3% of global energy demand (Figure 5, top). While we wait for this new technology and gradual transition, some quick emissions wins can come from the substitution of natural gas for coal.

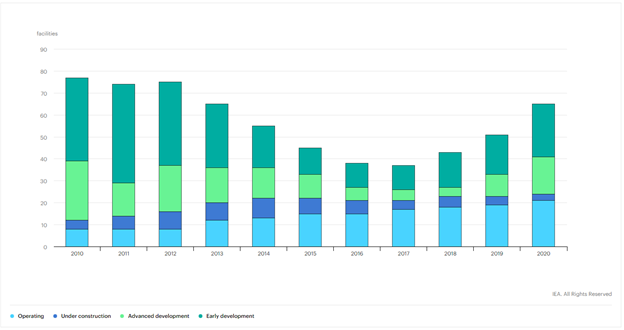

In practical terms, no energy source is intrinsically bad – it is the emissions that cause problems. If our objective is to reduce emissions, renewables are not the only way. Aside from a switch to natural gas, rapidly improving technologies are helping reduce GHGs from fossil fuels, and capturing carbon at the source and from the atmosphere (Figure 8).[11] All options can contribute to incrementally flatten and eventually reverse the curve.

Figure 8: World large-scale CCUS facilities operating and in development, 2010-2020.

Since we cannot expect renewables to meet global energy demand for decades to come, fossil fuels will continue to provide the affordable energy the growing world population requires for an equitable standard of living. Solutions to the “emissions crisis” will require co-operation between industry, academia, governments – and, perhaps most importantly, individual citizens – to consciously improve efficiency and establish an optimal, sustainable energy mix.

[1] United States Environmental Protection Agency, Overview of Greenhouse Gases, accessed Oct 13, 2021

[2] Our World in Data, Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from?, accessed Oct 13, 2021

[3] National Library of Medicine, Deoxyribonucleic acid, accessed Oct 13, 2021

[4] Bored Panda “Coffee_dante”: 30 Photos That Show The Terrifying Power Of The Taal Volcano Which Just Erupted In The Philippines, accessed Oct 1, 2021

[5] Johnson, M. S., Schwandner, F. M., Potter, C. S., Nguyen, H. M., Bell, E., Nelson, R. R., et al. (2020). Carbon dioxide emissions during the 2018 Kilauea volcano eruption estimated using OCO-2 satellite retrievals. Geophysical Research Letters, 47, e2020GL090507

[6] BP statistical review of world energy

[7] Comparison of Lifecycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Various Electricity Generation Sources, accessed Oct 13, 2021

[8] 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories

[9] There is a discrepancy in the emissions intensity attributed to various sources. The IPCC numbers were used where available for fossil fuels and the nuclear.org numbers were used for lifecycle emissions for renewables.

[10] Our World in Data, CO2 emissions by fuel

[11] World large-scale CCUS facilities operating and in development, 2010-2020, IEA, Paris

(Laurie Weston – BIG Media Ltd., 2022)

Chris – thanks for the positive feedback. I do hope this kind of non-alarmism spreads at least as effectively as the alarmist messages!

Great article, Laurie. Finally some real analysis and common sense suggestions around all of the climate alarm. This should be put in the hands of every attendee at COP 26. Thank you!