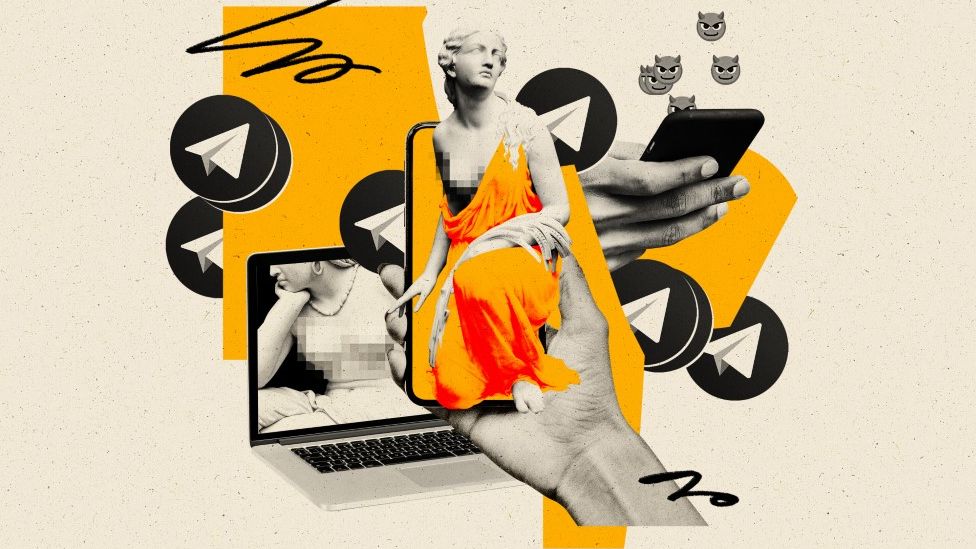

A BBC investigation has found that women’s intimate pictures are being shared to harass, shame, and blackmail them on a massive scale, on the social media app Telegram, the BBC reports.

In the split second Sara found out a nude photo of her had been leaked and shared on Telegram, her life changed. Her Instagram and Facebook profiles had been added, and her phone number included. Suddenly she was being contacted by unknown men asking for more pictures.

“They made me feel like I was a prostitute because [they believed] I’d shared intimate pictures of myself. It meant I had no value as a woman,” she says.

Sara, not her real name, had shared the photo with one person, but it had ended up in a Telegram group with 18,000 followers, many from her neighbourhood in Havana, Cuba. She says she fears strangers in the street may have seen her naked. “I didn’t want to go out, I didn’t want to have any contact with my friends. The truth is that I suffered a lot.”

She’s not alone. In months of investigating Telegram, BBC found large groups and channels sharing thousands of secretly filmed, stolen, or leaked images of women in at least 20 countries. There is little evidence the platform is tackling this problem.

Thousands of miles from Cuba, Nigar is having to adjust to a new life.

She’s from Azerbaijan, but says she has been forced to leave her homeland. In 2021, a video of her having sex with her husband was sent to her family, and then posted in a Telegram group.

“My mum started crying and told me: ‘There’s a video, it was sent to me,’ ” she says. “I was devastated, absolutely devastated.”

The video was shared in a group with 40,000 members. In the footage, Nigar’s now ex-husband’s face is blurred but hers is clearly visible.

She believes her ex secretly filmed her to blackmail her brother, a prominent critic of Azerbaijan’s president. She says her mother was told the video would be released on Telegram unless her brother stopped his activism.

“They look at you as if you are a disgrace. Who cares if you were married?” says Nigar.

Nigar says she confronted her ex-husband about the video, and he denied making it. BBC tried to get a comment from him, but he did not reply.

Nigar is still struggling to move on with her life: “I can’t recover. I see therapists twice a week,” she says. “They say there is no progress so far. They ask if I can forget it, and I say no.”

The pictures of Nigar and Sara were both reported to Telegram, but the platform did not respond. Their experience is not unique.

The BBC has been monitoring 18 Telegram channels and 24 groups in countries from Russia to Brazil, and Kenya to Malaysia. The total number of subscribers is nearly two million.

Personal details such as home addresses and parents’ phone numbers were posted alongside explicit pictures.

BBC journalists saw group administrators asking members to send intimate images of ex-partners, colleagues, or fellow students to an automated account, so they could be published without revealing the identity of the sender.

Telegram now says it has more than half a billion active users worldwide – that’s more than Twitter – with many attracted by its emphasis on privacy.

Millions moved to Telegram in January 2021 from WhatsApp, which changed its privacy terms.

Telegram has long been popular with pro-democracy protesters in countries with media censorship. Users can post without sharing their name or phone number, and create public or private groups with up to 200,000 members, or channels that can broadcast to an unlimited number of people.

Despite Telegram’s reputation for privacy, only the “secret chat” option provides end-to-end encryption, which ensures just the two people talking can see the message. It’s the default setting on secure chat apps including Signal and WhatsApp.

The platform also attracts users seeking a less regulated space, including those who have been banned from other platforms.

“According to Telegram and its owner, they don’t want to censor users,” says Natalia Krapiva, tech legal counsel at digital rights group Access Now.

But BBC research has shown this light-touch approach to moderation has led Telegram to become a haven for the leaking and sharing of intimate images.

Telegram does not have a dedicated policy to tackle the non-consensual sharing of intimate images, but its terms of service make users agree “not to post illegal pornographic content on publicly viewable Telegram channels, bots, etc.”

It also has an in-app reporting feature across both public and private groups, and channels where users can report pornography.

To test how rigorously Telegram enforced its policies, we found and reported 100 images as pornography via the in-app reporting feature. One month later, 96 remained accessible. The BBC could not locate four others, as they were in groups that could no longer be accessed.

Disturbingly, while the BBC was investigating these groups, an account from Russia also tried to sell the journalists a folder containing child abuse videos for less than the price of a coffee.

The writers reported it to Telegram and the Metropolitan Police, but two months later the post and the channel were still there. The account was only removed after the Telegram media team was contacted.

Telegram does take action against certain content.

After Apple briefly removed Telegram from its app store because of videos such as the ones the BBC was offered, Telegram took a more proactive stance on child abuse images. The platform also co-operated with EU crime agency Europol in 2019 to eliminate a huge amount of Islamic State content that had proliferated on the platform.

“We know that Telegram can remove and [has] been removing terrorist-related content or some kind of very radical political content,” says Dr Aliaksandr Herasimenka, researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute.

But the removal of intimate images appears not to be a priority.

The BBC spoke to five Telegram content moderators on condition of anonymity. They said that they receive reports from users via an automated system, which they said they sort into “spam” and “not spam”.

They said they don’t proactively search for intimate images and, as far as they know, Telegram doesn’t use artificial intelligence to do that, either. This lack of action has led some women to take steps themselves.

Joanna found a naked image of herself from when she was 13 years old in a notorious Malaysian Telegram group.

She created a fake Telegram profile to join the group, where she anonymously searched for nude pictures and reported them. She also shared her findings with her friends.

Amid intense media pressure, the group was eventually closed down. But during the course of our investigation, the BBC found at least two duplicate groups sharing the same kind of images.

“Sometimes you just feel so helpless, because we tried to do so much to remove these groups. But they’re still coming up, so I don’t know if there’s an end to it, honestly,” says Joanna.

Telegram declined an interview, but in a statement it told the BBC it does proactively monitor public spaces and process user reports about content that violates its terms of service.

Telegram did not confirm if posting people’s intimate images without consent is allowed on the platform, or whether they are removed.

The rollout of ads on some public channels on Telegram – along with investment – has signalled that founder Pavel Durov is intending to monetize the platform.

This is likely to increase pressure on Telegram and its libertarian founder to fall more in line with social media rivals such as WhatsApp, which has started to introduce policies against sharing intimate pictures.

It remains to be seen how long the company will resist greater moderation as it moves into new markets and starts to generate revenue.

For the women whose reputations have been destroyed and lives damaged by the sharing of their intimate images on Telegram, change cannot come soon enough.