There are at least two ways to look at just about every event, each differing significantly. Whether it is the Canadian truckers’ protest against COVID mandates, the current conflict in the Ukraine, feelings around racial issues, or any other social issue, there will never be unanimity in perception and viewpoint.

Often, disagreement is conveyed in passionate and dogmatic terms, with those on the other side of the divide being viewed pejoratively. Look no further than the news media or social media for examples.

As strong as we may ourselves feel about an issue, in different circumstances we might find ourselves arguing for the opposite conclusion. Hypocrisy is common, and rarely detected in oneself in the heat of the moment.

It can be difficult to face the level of bias, prejudice, and hypocrisy that is evident in the news, and in our own reaction to it. We find we support one protest and not the other, cheerfully accept refugees from some countries and shun others, or revile some skin colours and protect others. It is even tougher to be honest about our inability to fundamentally change our tendency to do these things – to act hypocritically. And when I say “we”, I don’t mean someone else, I mean you and me. We are no better than anyone else; there is no value in heaping our flaws on someone else or imagining that we are somehow superior or immune to these failings.

We must own this despite it being that, in human nature, someone else is preferably held to blame and not ourselves. We tend toward a selfish interpretation of circumstance.[1]

It may sound like I am calling us all selfish, biased, hypocrites, but that would be taking it too far. The point is being put forward as a pathway to hope. We need to understand our own tendencies in order to improve. For we have not changed, only our understanding of self. Our path to progress is not through an imagined or inherent virtue, but through a better understanding of our flaws.

Fundamental attribution error

In this article Nudge and the uneasy pursuit of context and objectivity, we spoke of cognitive biases – tendencies for human beings to act irrationally in certain ways. An important and arguably foundational cognitive bias that we did not previously discuss is fundamental attribution error (FAE).[2]

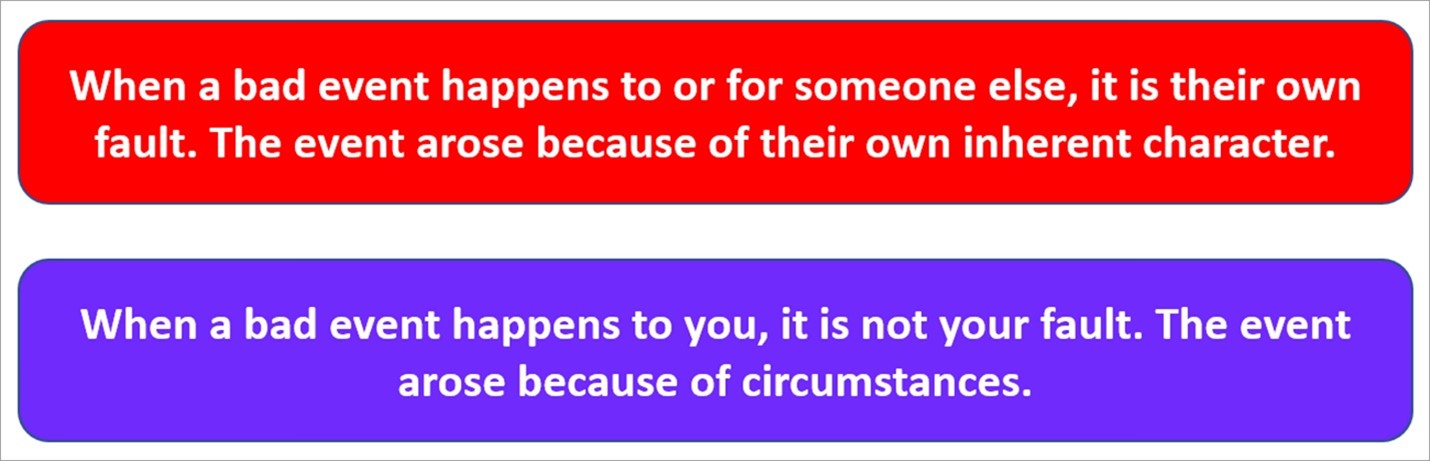

FAE is the idea that when bad things happen to others, we tend to assign blame to them and their inherent qualities, or character, while when bad things happen to ourselves, we tend to blame it on circumstances. The opposite causation is applied for good events. This concept is captured in the image below.

FAE has been demonstrated in numerous behavioural studies, although the underlying causes are speculative. Some psychologists believe that FAE could have an evolutionary basis.[3]Whatever its cause, FAE is a kind of self-centred unfairness.

It plays to the concept of hypocrisy, or double standards – that we apply a different set of rules to others than to ourselves. Further, FAE demonstrates that we allow our behaviour to be ruled or forgiven by circumstances, but do not tend to apply that fluidity and grace to others.

Fundamental attribution error, arguably the foundation of behavioural psychology, exposes the tendency to be unfair and hypocritical.[4][5][6]Good events are causally flipped.

Like the other cognitive biases, FAE is a tendency, not a deterministic rule. It can be minimized.[7]Let us see look at some examples of our potential unfairness.

Recent examples illustrating that our reactions are often inconstant

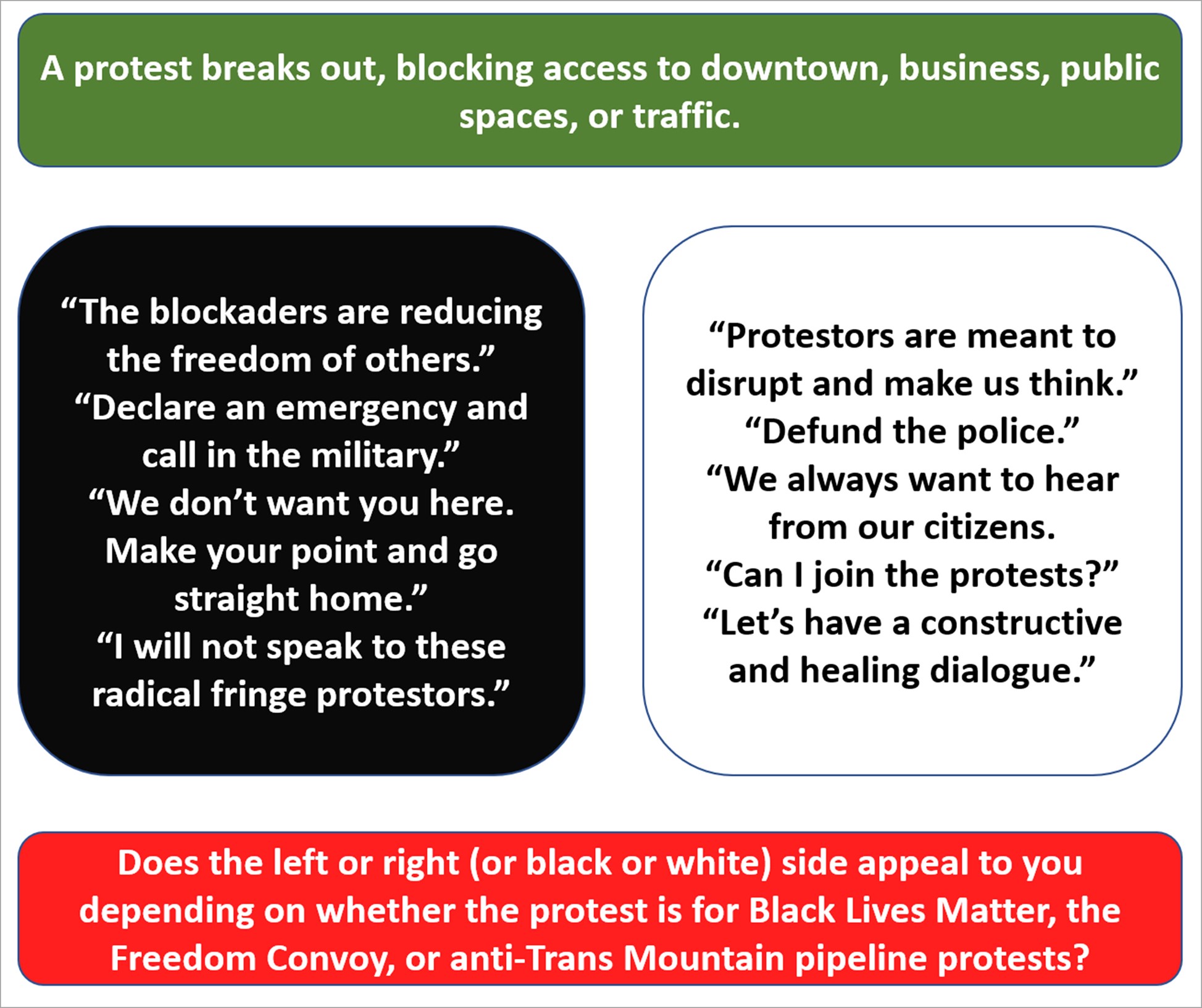

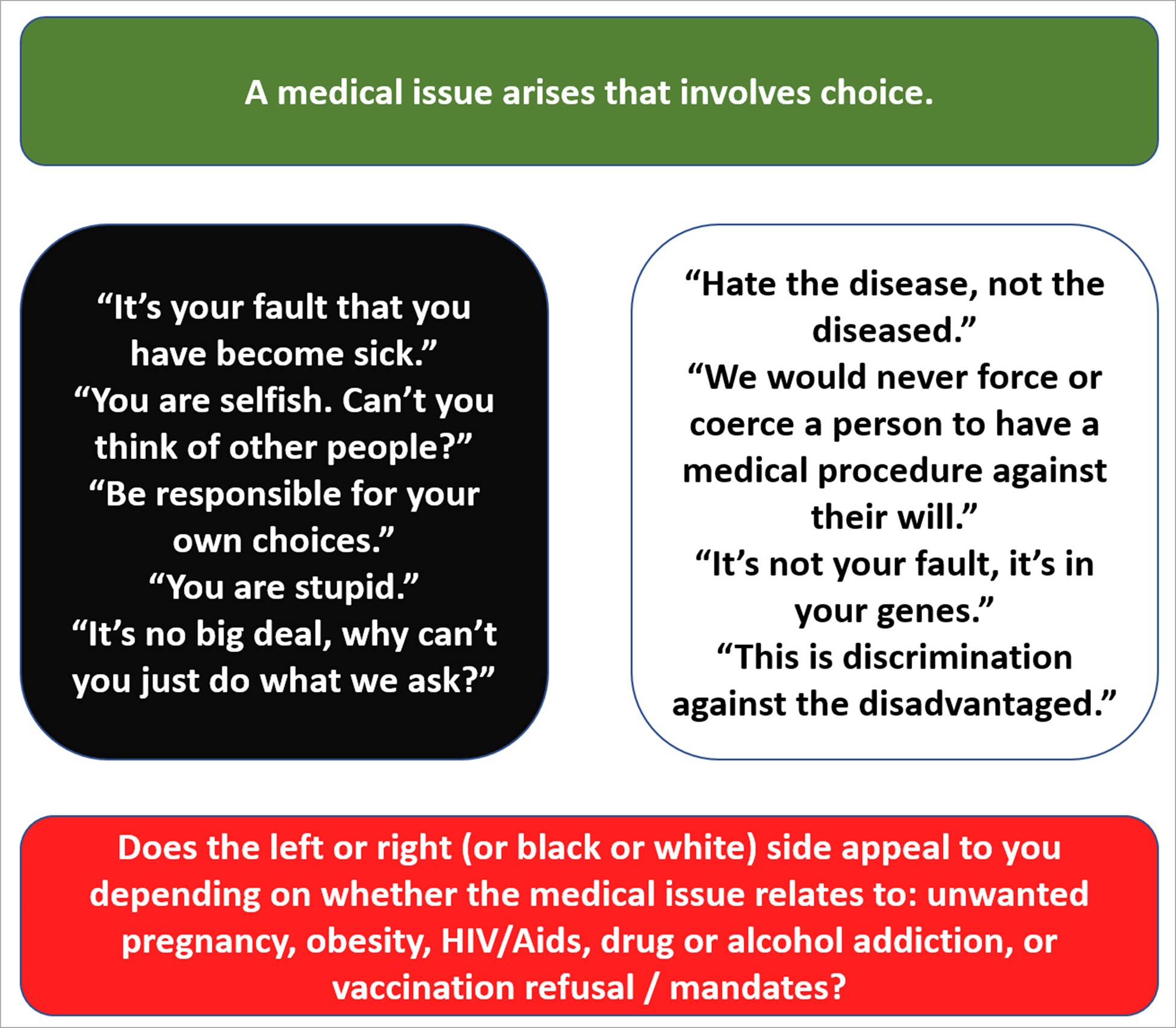

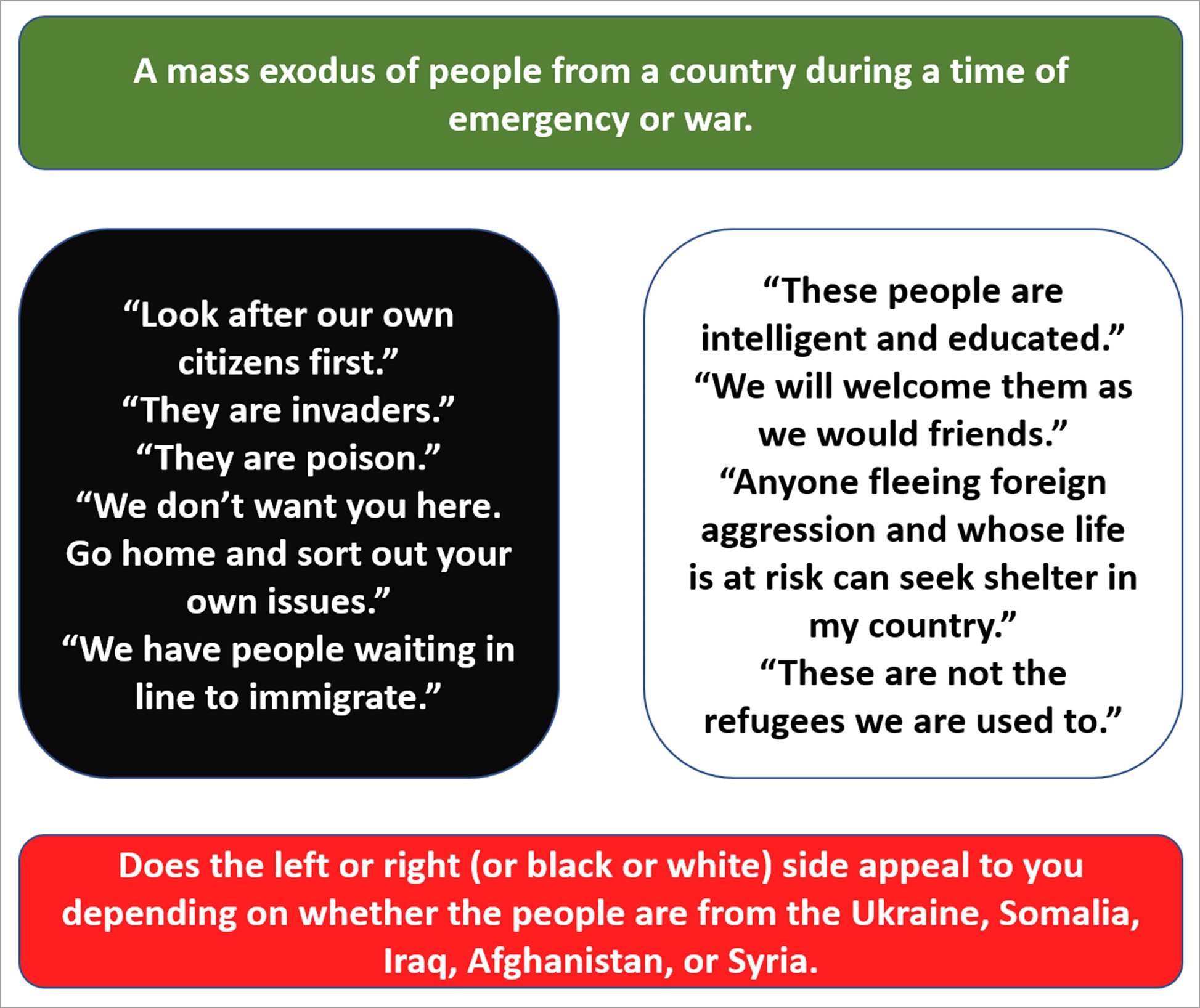

Readers can examine for themselves three hypothetical examples that illustrate unfairness in evaluating events. These events are taken from recent history. Each example has an event or situation, and two responses to it: one sympathetic and the other unsympathetic.

The task for readers is to ask themselves if they have ever taken sides depending on their subjective experience or circumstantial relationship to the events.

The first example involves protest. There have been numerous protests around the world over the last few years, including the recent Freedom Convoy, Black Lives Matter, and the anti-Trans Mountain pipeline. Politicians have been on either side of these protests, and the following example paraphrases some of their public remarks.[8][9][10]Have you been constant in your response to these protests?

The second example has to do with bioethics and is relevant to research from two recent articles in BIG Media, Examining the ethics of triage in a pandemic and Mounting COVID frustration is no reason to abandon fundamental principles. We consider numerous undesirable medical situations: unwanted pregnancy, obesity, HIV infection, drug or alcohol addiction, or a conflict over mandated vaccination. Each of these situations potentially has an element of personal choice or lifestyle involved. Are we more sympathetic to some of these situations than others? Have we argued both sides of the same principle?

The third example refers to a humanitarian crisis, particularly one involving refugees, where there is a mass exodus of people needing shelter in another country. The example quotes are largely paraphrased from politicians’ remarks regarding Somalia (1990s), Syria (2015), Iraq and Afghanistan (2021), and Ukraine (2022).[11]Do the readers feel sympathetic or unsympathetic to each of these situations? Have we always been on the same side of the response?

The most golden of rules

While these examples show that unfair reactions to events have happened, and are occurring now – and, further, that our lack of a uniform response may be part of the human condition – the point here is not that we are doomed to be hypocrites. As discussed in this article Nudge and the uneasy pursuit of context and objectivity, we are capable of being fair and rational. But being aware of FAE – or any cognitive bias – does not render us immune to the bias. We do not enter a state of virtue with these irrational tendencies. The best way to minimize such behaviour is to recognize they are real and enact processes to help us recognize them in everyday life.

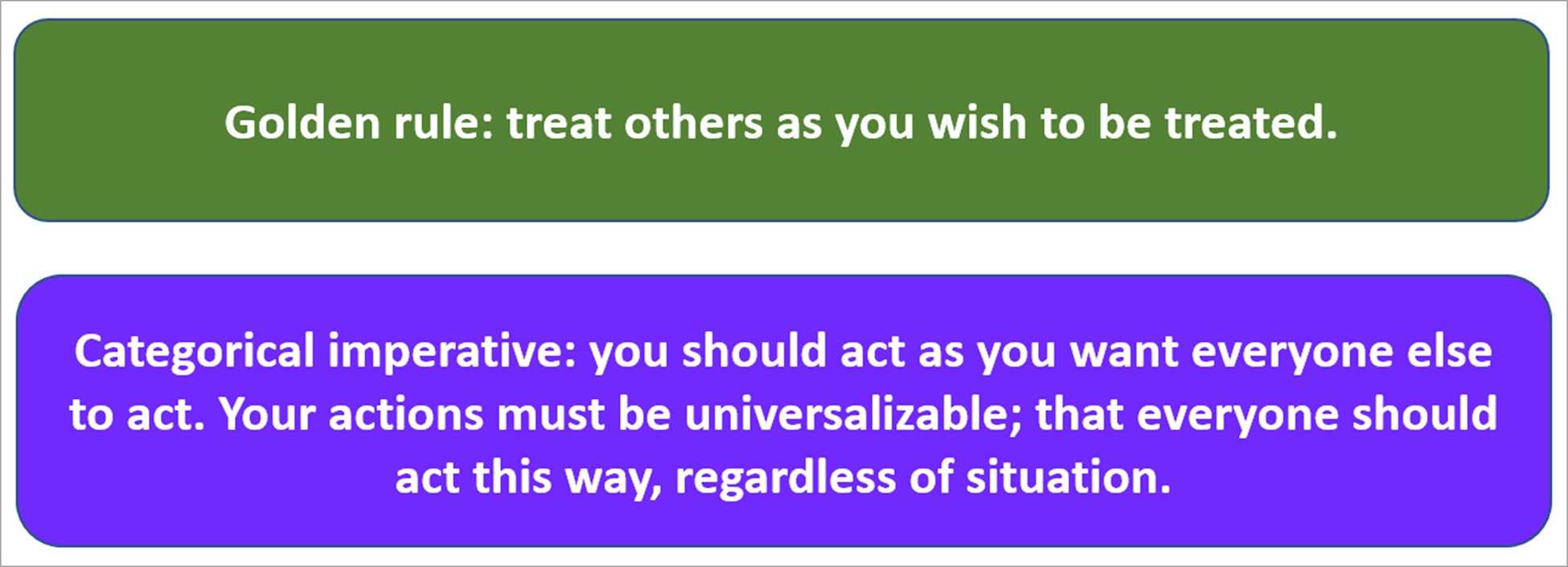

In the 18th century, philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed a process that he called the categorical imperative, which may be a useful method in finding fair evaluation to actions. Kant suggested that any action must be universalizable.[12]That is, the action must be so broadly applicable that the reader would want anyone to act in such a way, regardless of their particular situation. The categorical imperative is a step beyond the golden rule (see the illustration below), which asks that we be treated as we wish to be treated. Kant’s imperative demands that the treatment be something we would want to be applied by anyone, anywhere.

Kant’s categorical imperative is a step more beatific than the golden rule.[13]

As moral guidelines go, the categorical imperative is extremely difficult to apply in real life, as few actions are easily universalizable.[14]This ethical construct underlies much of the western ideas of justice and law. The law “being blind” is an example of this.

A process toward being more reasonable

If processes are the best way to minimize our hypocrisy, what process could we follow? We could do the following:[15]

- If the question concerns a person, ask if the judgement changes if it is you instead of them, or them instead of you. What if it is your child, or your grandma? What if the person is black? What if the person is white? What if the person is of each and every ethnic group? Does it make a difference? What if anyone you could think of is in this situation or acts this way?

- What if the situation involves your country, state, province, or city? What if it involves some other country? Does the problem seem different then?

Kant’s categorical imperative could be argued as naïve and unworkable, as circumstances may or may not be specifically relevant, however, it is a quick test of obvious fairness or unfairness.

The hypocrisy of Kant and what it teaches us

The categorical imperative shines a rather harsh light on racial prejudice, allowing little leeway in judging the historical prejudices against black persons in the United States. As a rule, this imperative is no more lenient on making generalizations against the white population of the same country, even if some were indeed the perpetrators of past injustices. Universalizability leaves no room for abuse or differential judgement based on skin colour, gender, or ethnicity.

There is a powerful lesson in the fact that Kant, the creator of this amazing imperative, himself taught a racial anthropology for many years, and treated persons of colour differently from white Europeans. The justification was that he said they were inferior and not subject to the same rules.[16]This is a level of hypocrisy on the same level of the Declaration of Independence that on the one hand states that “All men are created equal”, while on the other failing to address the ongoing practice of slavery by many of the document’s signors.[17][18]

What does this teach us?

These historical failures do not teach us that we are more enlightened; it teaches us that anyone is capable of irrational self-interest and FAE. There has long been a discussion of whether increasing moral justice is intrinsically guaranteed to increase with time.[19] But these failures tell us that it is not inevitable that the future will be better than the past. Humanity has not changed to become genetically more virtuous. If Thomas Jefferson can own 600 slaves and still hold that “All men are created equal”, then we should be warned that we might individually fail.[20]However, knowing that we are subject to these biases is a step toward progress.

That our institutions often fail to deliver the fairness and merit-based judgements that they are constructed to do is not reason to throw them away. The ideas, such as Kant’s categorical imperative, underlying many western justice systems remain some of the most fair-minded ideas humankind have ever had, and some of the best tools we will have toward being fair.[21][22]It is our failure to living up to and applying these ideals that we must admit.

Just as we are capable of being irrational or rational, biased, or unbiased, we can, with effort, aspire to greater fairness.

We may be no better, but we have reason to hope

We can never fully achieve the golden rule, nor Kant’s categorical imperative, but we can avoid some of Kant’s mistakes, and some of our own – because they have already happened, and stand as record of wrongdoing. We are not superior beings, but we have this one advantage, the advantage of history – if we choose to use these lessons, and use them with humility and dogged determination.

And so we should be hopeful, not because we are more virtuous or superior, for human beings have not abruptly changed. We are not born wiser and better. We can only be hopeful if we embrace that we are the same as we have always been – prone to favouring ourselves or those closest to us, quick to generalize, and tending to oversimplify complex issues. Our best hope comes from embracing not our virtue, but humility. That and drawing upon the knowledge of those who have both erred and learned before us to reach beyond our shortcomings, and try for something golden.

References

[1] McCombs School of Business, 2022, Fundamental Attribution Error, University of Texas

[2] McLeod, Saul, 2018, Fundamental Attribution Error, Simply Psychology

[3] The Jordan Harbinger Show, August 22, 2019, FAE: The Big Mistake You’re Making about Other People (And How to Overcome it)

[4] McCombs School of Business, 2022, Fundamental Attribution Error, University of Texas

[5] McLeod, Saul, 2018, Fundamental Attribution Error, Simply Psychology

[6] The Jordan Harbinger Show, August 22, 2019, FAE: The Big Mistake You’re Making about Other People (And How to Overcome it)

[7] Healy, Patrick, June 08, 2017, The Fundamental Attribution Error: What IT IS & How to Avoid It, Harvard Business School Online

[8] Jerema, Carson, Feb 06, 2022, Carson Jerema: Freedom Convoy reveals a Canada governed by hypocrisy and traffic jams, National Post

[9] Leedham, Emily, Feb 05, 2022, Canada’s “Freedom Convoy” Is a Front for a Right-Wing, Anti-Worker Agenda, Jacobin

[10] Mensch, Jennifer, 2017, What’s wrong with inevitable progress? Notes on Kant’s anthropology today, Cogent Arts and Humanities, 4:1

[11] Reliefweb, March 2, 2022, The Ukraine Crisis Double Standards: Has Europe’s Response to Refugees Changed?

[12] Kant, Immanuel, 1785, Groundwork of Metaphysical Morals, ISBN 978-1492204152, CreaterSpace Independent Publishing Platform 2013

[13] Effectiviology, Kant’s Categorical Imperative: Act the Way You Want Others to Act

[14] Potter, Nelson, 1975, How to Apply the Categorical Imperative, Philosophia (October 1975) 5(4): 395-416

[15] Effectiviology, Kant’s Categorical Imperative: Act the Way You Want Others to Act

[16] Mensch, Jennifer, 2017, What’s wrong with inevitable progress? Notes on Kant’s anthropology today, Cogent Arts and Humanities, 4:1

[17] Williams, Yohuru, June 29, 2020, Why Thomas Jefferson’s Anti-Slavery Passage was Removed from the Declaration of Independence

[18] Bouie, Jamelle, June 05, 2018, The Enlightenment’s Dark Side, Slate, News and Politics

[19] Mensch, Jennifer, 2017, What’s wrong with inevitable progress? Notes on Kant’s anthropology today, Cogent Arts and Humanities, 4:1

[20] Williams, Yohuru, June 29, 2020, Why Thomas Jefferson’s Anti-Slavery Passage was Removed from the Declaration of Independence

[21] Bouie, Jamelle, June 05, 2018, The Enlightenment’s Dark Side, Slate, News and Politics

[22] Jordan, Vernon, June 7, 2017, A Celebration of Black Lawyers, Past And Present, The New Yorker

(Lee Hunt – BIG Media Ltd., 2022)