“Progress depends on retentiveness. [W]hen experience is not retained, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

– George Santayana

Many of the policy responses to COVID-19 in the United States, Canada, and much of the rest of the world have been more a series of wobbly missteps than a steady march on the road to victory. The resulting stumbles occurring over the last two years are neither new nor unique.

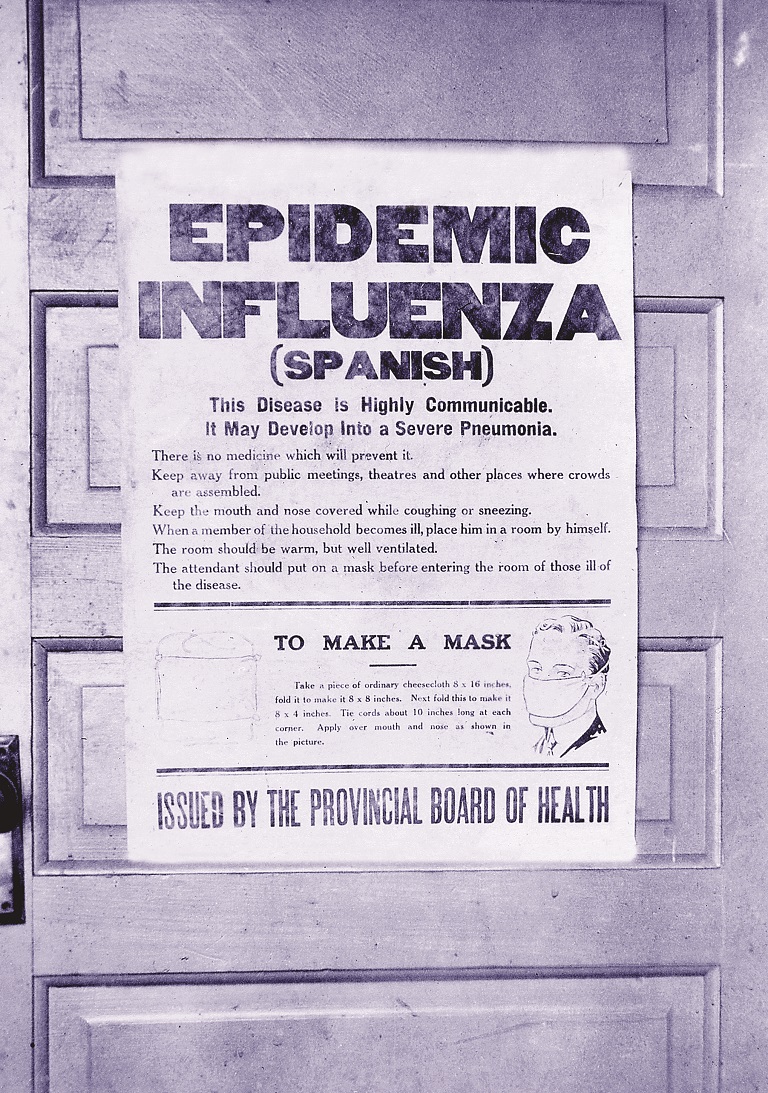

Restrictions and mandates that have been imposed on the public since March 2020 were also used against the spread of influenza at other times in history, including the influenza pandemic in 1918-1919. In my home province of Alberta, to combat Spanish Flu outbreak near the end of the First World War, the provincial board of health opted for an array of compulsory measures beyond those taken in other Canadian provinces. Those included quarantining, closures of schools, churches, and theatres, banning public gatherings, and wearing masks in public.

Employees from the Canadian Bank of Commerce in Calgary during the Spanish flu epidemic. Wearing masks in public was made compulsory by the Alberta government on Oct. 25, 1918. Source: Glenbow Archives/NA-964-22. In Regina, meanwhile, coughing, sneezing, and spitting in public became finable offences.

The parallels to 2020/21 are striking, but the focus of this article is not to highlight similarities in public health measures a century apart. The purpose is to appreciate the value in looking at the retrospect: to see “what was said” in the context of past pandemics and compare it to how things turned out.

One excellent article on the 1918 Spanish flu policy response is “The Practical Aspects to Quarantine for Influenza” by former Alberta Medical Officer of Health T.H. Whitelaw. It appeared in 1919 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal as one paper in a series of articles in which practising physicians and medical officers of health reflected on Canada’s campaign against the influenza. In the early period of the epidemic, many expressed doubts that overly restrictive measures could contain the disease. Eventually, from the perspective of Whitelaw and others, compulsory measures turned out to be ineffective and needlessly blunt instruments. There was a sense of defeat among many, both in terms of containing and preventing infection, and in the treatment of those severely ill.

In his article[1], Whitelaw writes:

“[T]he apparent futility of practically all measures of prevention, some of which were, at the outset, acclaimed with great assurance by members of [the medical] profession… Had [these orders] been instituted a few days before the epidemic reached its peak, [they] probably would have been acclaimed as the chief factor in bringing about the rapid subsidence of the epidemic, but unfortunately for the extravagant claims made in justification of the [orders] as a means of prevention…public confidence…soon gave place to ridicule.”

This poster, issued by the Alberta Provincial Board of Health, provides information on Spanish flu and instructions on how to make a mask. Source: Glenbow Archives/NA-4548-5.

Replete with hindsight, looking back at Whitelaw’s account is crucial because it is testimony signalling that strict policy responses – even in 1918 – represented a step backward for the ideals of public health. Then, as now, policy decisions disrupted society and constrained freedom in the presence of, as Whitelaw called it, an “insidious and extremely prevalent” infection. The disadvantages, it seems, from the standpoint of prevention and control, outweighed the advantages. As it turned out, public health officials didn’t know as much about controlling influenza as they thought.

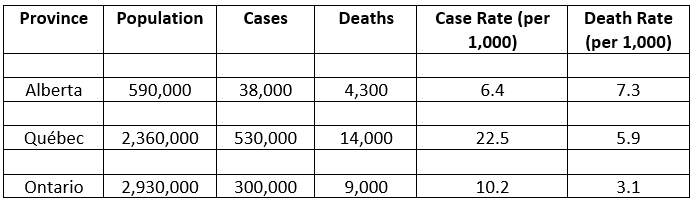

Alberta, for example, had some of the worst outcomes regarding fatalities despite using one of the largest arrays of restrictive measures. While many cases and deaths in 1918 were either not reported, or mis-diagnosed[2], the death rate per 1,000 people has been documented to be 1.3 to 2.4 times higher than Québec and Ontario, respectively (see Table below).

Population, cases, and deaths are approximations taken from[3]and[4]. Case rate = (cases/population) * 1,000; death rate = (deaths/population) * 1,000.

Looking back on the experiences of 1918, Whitelaw and his contemporaries declared that suitable response strategies would not be achieved by criticizing an “ignorant public”, nor would epidemics be contained using punitive measures and the full force of emergency law.[5]Instead, the policy aftermath of the 1918 pandemic shifted the balance between public health precautions and the rights of the community, to autonomy and freedom from coercion.

Post-pandemic, Whitelaw concluded, that “sane and reasonable” approaches to managing infectious disease were needed:

Following the world war, we hear a great deal about co-operation in all lines of human endeavour. Would it not be possible to secure a greater measure of co-operation … by reorganization and revision of [our public health measures] along the lines of sane and reasonable regulations which are in accord with the latest and most reliable information derived from scientific investigation, experiment, and experience?

Comparing Whitelaw’s sentiment to the responses taken in 2020/21, I find myself pondering what is bound to perplex many: did our leaders, through their actions, strike a balance between public health precautions and the rights of the community?

The truth is, we did not heed Whitelaw’s advice. Instead of adopting inclusion, citizenship, and the public’s right to voluntary commitment to disease control, we engaged in fear mongering, COVID-19 detention camps (see Australia), coerced vaccination, and intolerant conformism that excluded whole segments of society (vis-à-vis Austria and Germany) – all of it peddled through a drumbeat media consensus and the organised censoring of dissent.

We have been compelled to accept a completely new vocabulary designed to disguise what has happened: we’ve been “flattening the curve” through “layered mitigation strategies”, “non-pharmaceutical interventions”, and “social distancing”. When translated, we were placed under house arrest, had businesses and schools closed, were disallowed to gather in public, and were saying goodbye to dying loved ones over Zoom. But questioning these measures publicly has been deemed socially unacceptable.

None of us has a crystal ball. And while any expert can make an educated guess, we do not know what the next pandemic’s impact on humanity will be. While it is good to be prepared for a pandemic, we must remember that they will continue to come and go.

History has shown us that closing society is not beneficial when looking at the big picture. The restrictions over the last two years certainly had an impact on public health; for example, the virtual disappearance of the flu in 2020[6]– that may have contributed to higher levels of COVID infection. There is also evidence to suggest that measures professed to help contain COVID-19 are linked to high levels of excess (non-COVID) deaths across different age groups.[7]

Public health practitioners learned in 1918 that dramatically restricting people’s lifestyles comes at a toll that extends beyond short-term inconvenience. The current generation of medical experts has re-learned the lesson in recent months.

Unless there is a thorough inquiry, where politicians and health officials are held accountable for the past two years, we (to quote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn) “purely and simply [deserve] everything that happen[s] afterwards.”[8]

As the third year of our COVID-19 coexistence begins, and restrictions are being lifted worldwide, people’s attention toward this pandemic is dwindling. For many, this might mean we have entered a sweet period in which people are just happy that the worst might finally be behind us. For our governments and public health institutions, this is a chance to demonstrate a willingness to endure the painful contemplation required to learn from past mistakes and avoid the desire to simply “move on”.

Let’s not forget – we were not doing this from scratch.

References

[1] Whitelaw, TH. The practical aspects of quarantine for influenza. CMAJ 1919; 9(12): 1070-74

[2] McGinnis, JPD. The Impact of Epidemic Influenza: Canada, 1918-1919. Historical Papers / Communications Historiques 1977; 12(1): 120-140.

[3] McGinnis, JPD. The Impact of Epidemic Influenza: Canada, 1918-1919. Historical Papers / Communications Historiques 1977; 12(1): 120-140.

[4] Government of Canada. Sixth Census of Canada, 1921, 1921.

[5] Jones, EW. Co-operation in All Human Endeavour: Quarantine and Immigrant Disease Vectors in the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic in Winnipeg. Can. Bull. Med. History 2005; 22(1): 57-82.

[6] Weston, L. Where did the flu go – and do we miss it?. Big Media 2021

[7] Weston, L. Analysis of excess deaths in 2020 reveals surprising deviations. BIG Media 2022.

[8] Solzhenitsyn, A. The Gulag Archipelago. Harper & Row, 1973.

(David Vickers – BIG Media Ltd., 2022)